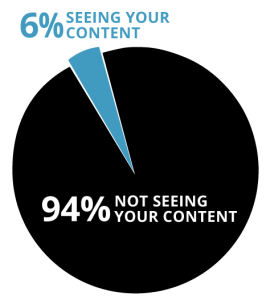

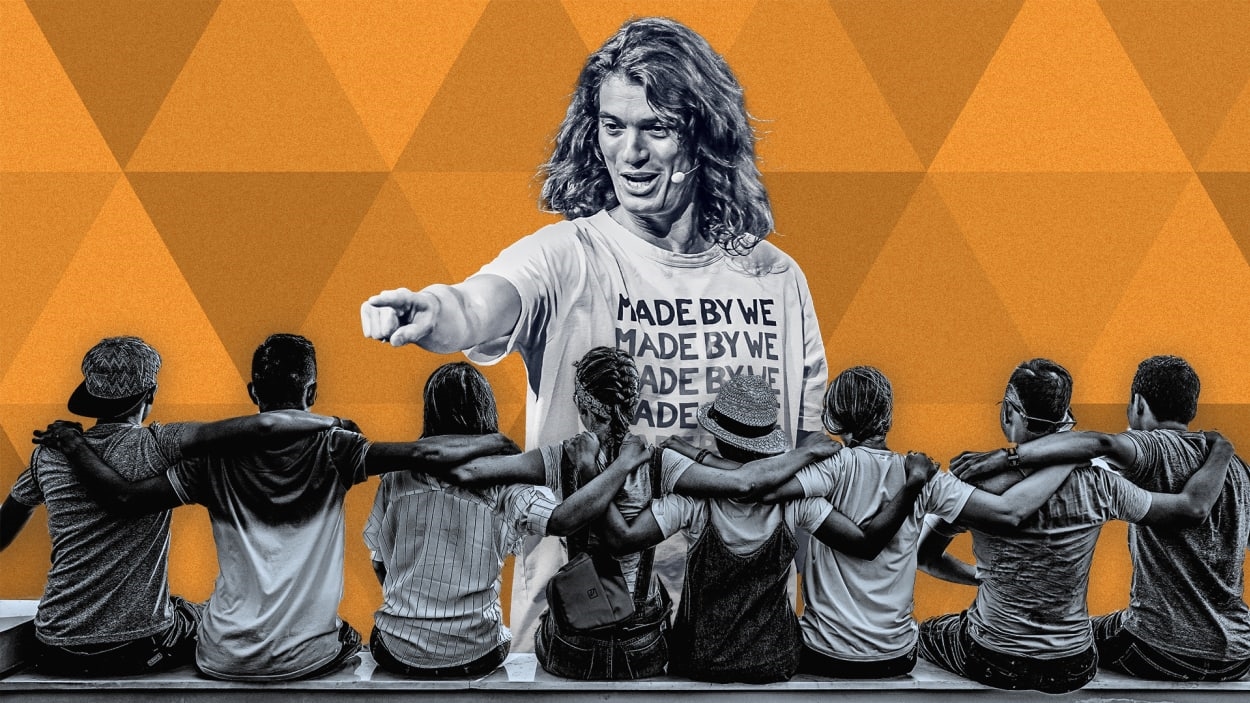

Everybody’s curious: What exactly is Flow, Adam Neumann’s new rental-housing startup that’s apparently snagged the largest check ever written by Silicon Valley VC firm Andreessen Horowitz? The reason for the curiosity is that, so far, Neumann and a16z aren’t saying much, beyond vague gestures at concocting some kind of housing utopia for remote workers: “Exact details of the business plan could not be learned,” the New York Times acknowledged in its story about a16z’s $350 million mega-investment.

Based on cofounder Marc Andreessen’s blog post—which announced the firm’s involvement on Monday—Flow sounds ambitious: America can’t fix its housing shortage with more multi-decade mortgages (the digital-nomad class doesn’t want to be “stuck”) or “soulless” apartment rentals that create no bonds “between person and place” or “person to person.” Andreessen explains Flow will solve this problem by “combining community-driven, experience-centric service with the latest technology . . . to create a system where renters receive the benefits of owners.”

To wit, Neumann has already acquired some 3,000-plus apartment units in Atlanta, Fort Lauderdale, Miami, and Nashville. They’re now ready to get the Flow brand’s full living-experience treatment. There are, of course, many other components to this plan, but the Flow living experience sounds like the concept that’s been trending for years now, perhaps best described as WeWork meets amenities-packed commune (or kibbutz, on which Neumann grew up, in part).

If that’s where Flow is headed, it’ll have a massive war chest in tow—valued at over $1 billion before doors ever open. And that could come in handy because it will also need to offer a better experience than the one that dozens of its failed or struggling forerunners have. Here’s a few:

HubHaus

Offering “dorms for grownups,” this startup imploded in 2020, after four years and $13.4 million raised. The model was remarkably WeWork-like: It leased big homes in Los Angeles, Washington, D.C., and San Francisco, decorated and furnished the common areas, then sublet the bedrooms to young working professionals. Its pitch was affordable accommodations in markets where rents were exorbitant, but with extra perks like fast Wi-Fi, cleaning services, and a readymade community of new housemates.

But the pandemic brought months of losses on rent, causing HubHaus to lay off about half of its employees, quit paying its properties’ utility bills, and in fall 2020, finally announced it was closing. Landlords and tenants were told to figure things out on their own. Founder Shruti Merchant blamed HubHaus’s downfall on “two major outside events”: COVID-19 and WeWork’s failed IPO, which she argued was so radioactive that startups in coworking or related niches could no longer raise series B funding.

Campus

Started by a Thiel Foundation fellow named Tom Currier, Campus lasted for two years as a co-living experiment, occupying nearly three dozen properties in New York City and San Francisco. Like HubHaus, the company leased large properties, then sublet rooms to individuals who bought into Campus’s mission of building community by effectively corralling tenants into residences where the people had similar interests. Beyond monthly rent, members were charged a service fee that included perks like toilet paper refills and professional apartment cleaning. Unfortunately, this meant they were paying a premium above market rate to live with roommates—but they still lived with roommates.

Campus bit the dust in 2015. “Despite continued attempts to alter the company’s current business model and explore alternative ones,” Currier wrote, “we were unable to make Campus into an economically viable business.” At the time, Fast Company’s Sarah Kessler was fresh out of six months of living in one of Campus’s Brooklyn residences, and she concluded: “While Campus, the business, was a failure, Campus, the living situation, was a success.”

Common Living

Among the few communal-living startups to argue it was going to succeed where Adam Neumann failed—then actually manage to survive COVID-19—this venture with more than $100 million in VC backing has since run into problems of its own making. Namely, in May, over a dozen residents told the Daily Beast that living in Common housing is a complete “nightmare.” They described violent altercations among housemates, lingering piles of uncleaned vomit and other maintenance delays, and security so poor that in the mornings they were frequently finding strangers asleep in the common areas. “It’s been probably one of the worst experiences living somewhere I’ve ever had in my 38 years on this planet,” one tenant complained.

Common was founded in 2015 with the goal of giving adults a cheaper group-living setup. It merely acts as property manager for landlords, putting their buildings under the rule of Common’s co-living arrangement. It’s doubled its portfolio in the last two years to 7,000 units under management. “We really want to make the experience of renting better,” cofounder and CEO Brad Hargreaves says.

Flow Living

Plenty of community-driven rental startups with lesser-known names have come and gone—Krash, Pure House, and a myriad of others that simply went belly-up. But one worth noting, if just because of its coincidentally similar name, is Flow Living. Roger Norton, part of the team that helped start it, said on Twitter that this version dates back to 2017, and describes the premise as “‘club’ living for Gen Z” that provided “Everything you need to live ‘in the flow.’”

At move-in, Norton explains, residents picked a predetermined “style” for their room to come outfitted in. At any time, they could move to another Flow Living building. Meanwhile, private chefs, laundry, coworking space, and movie theaters were at their beck and call, all managed by app. Ultimately, Flow Living struggled to raise funding though, he notes, adding it “ended up pivoting for rental landlords to manage their properties with contracts, rent collection, and ticketing.”

WeLive

Finally, if the branding for this one looks familiar, it’s because this was Neumann’s OG stab at communal living. The concept began in two buildings—one in New York City, the other in northern Virginia—and had a pretty unshakable adult-dorm-room vibe, which WeWork leveraged to market the experience to excitable young professionals: The rooms were indeed teeny tiny studios, yet there was free beer on tap, the laundry room had a pool table, and dinners were cooked for you, and served communally. (Anyone who’s seen WeWork: Or the Making and Breaking of a $47 Billion Unicorn may recall having these experiences described by WeLive resident/official ambassador August Urbish.)

Neumann once predicted the globe would be scattered with WeLives, and at one point was working to expand into India and Israel. But the concept fizzled after the initial two locations opened and New York City housing officials got interested. They started investigating if WeLive’s units, which were legally required to be rented as apartments, were instead being advertised by WeLive as hotel rooms.

(21)

Report Post