By Jennifer Alsever

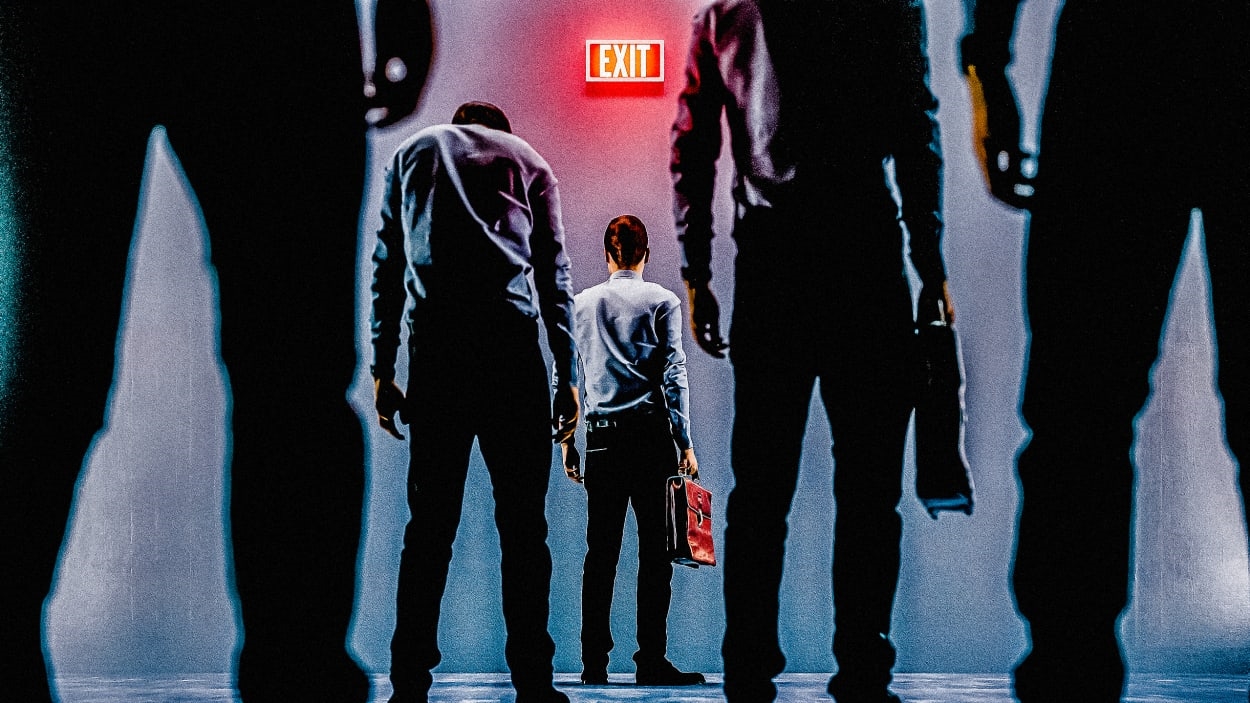

The uber-tight labor market has prompted employers to speed up the hiring process to land the best candidates before they disappear—and increasingly, software is helping to make those job offers.

Speed is everything in today’s job market. The nation’s unemployment rate held steady at 3.7% in November, the most recent data available, and the 10.5 million job openings outpaced the 6.1 million people seeking work. The result is an unprecedented labor shortage that has put employees firmly in the driver’s seat. They’re bargaining better, commanding higher salaries, and entertaining multiple job offers.

A large swath of companies are dropping college degree requirements, boosting internal promotions, and accelerating the time to hire. Some, including UPS, Home Depot, and the Gap are even going so far as to skip the job interview entirely.

But the key to hiring fast increasingly relies on AI software: 70% of companies now rely on automated tools for scoring candidates and conducting background checks, and AI-enabled tools are matching skills to jobs. This can happen in minutes and cut the time to hire to 35 to 40 days on average.

“If you don’t get somebody through the process fast, you’re going to lose them,” says Josh Bersin, CEO of the Josh Bersin Company, which analyzes the talent market and trends impacting the global workforce.

Opportunity knocks fast

Nine in 10 of new hires who got a new job within the past six months said they heard back from their current employer within a week, according to a survey by ZipRecruiter. At least half of them (50.3%) heard back within three days after applying for jobs.

Chatbots with names like iCims, Phenom, and SmartRecruiters now enable a candidate to submit a résumé and book an interview on the spot. Artificial intelligence tools like Jobvite, Modern Hire, VidCruiter, and HireVue now assess and score a person’s word choice, micro gestures, and overall answers in recorded video interviews. Software tools like Predictive Index, Harver, and Plum prompt candidates to do interactive job scenarios and take online tests, and then scores them and sends the best job candidates on to do interviews.

A jewelry store might give a candidate an interactive video test in which she is asked how to handle a customer who thinks a necklace is too expensive. Do they talk the customer into buying it? Find them something less expensive? “They’re trying to quickly decide if this person is a good fit—and it works,” says Bersin.

For hourly job openings, McDonalds uses a Paradox.ai, an AI chatbot that asks the candidate questions about their job history and where they live and the hours they can work. The system conducts a background check, and if the person is qualified, he gets a job offer. The software cut the hiring process to one to two days from 10 to 14 days.

Florida PR firm Otter started using software by Breezy HR to keep its pipeline of candidates moving. The 52-person firm intends to hire 12 people in the next six months, and the software constantly alerts the team of new people in the pipeline. It prompts candidates to do an online writing assessment, scores those tests and sends top contenders to another round of tests. The scores get sent to the Otter team each week, and after a group meeting, they decide who gets interviews and job offers.

“It gives us insight into their capabilities,” says Tiffani Martinez, Otter’s head of HR. “Because sometimes people look really good on paper and they’re not as good fit in the role.” Better yet, it takes just one week from application to job offer.

The accelerated hiring process comes with risks. There is still concern that AI may promote biased hiring. Critics contend it perpetuates a status quo because it uses unconsciously prejudiced selection patterns, such as language and demography, and is programmed on biased and inadequate data sets.

And sometimes quick hires aren’t always the best ones, says Kelly Robinson, CEO at Panna Knows, an HR consulting firm. “Companies are cutting çorners,” she says, and many have consequently paid inflated salaries, some paying $50,000 more than normal—just to get someone into the position.

“They’re overpaying and not getting the [best work],” Robinson adds. “We advise all our clients to slow it down.”

(30)

Report Post