Apple and Samsung are the McCoys and Hatfields of the tech industry—they seem to hate each other. Besides suing each other over patent rights, each is trying provide the “better user experience” on a mobile device. That’s the nature of competition. However, you should never let intense competition get in the way of mutual interest. Which is why Apple recently awarded a major contract to manufacture chips for its iPhone and iPad product lines to Global Foundries—whose strategic partner is none other than Samsung.

This is also why despite the legendary Mac vs PC ads that posited a Bill Gates look-alike as an unhip, clueless geek, Microsoft continued to supply a Mac version of its Office Suite software. And that the two “enemies” have cooperated in licensing mobile operating system features and patents.

As The Wall Street Journal Small Business Report notes, sometimes a tough competitor can be a good partner. The key is mutual self-interest to create a situation in which both partners win. As noted by the Harvard Business Review, collaboration fails when one stakeholder assumes success can only come at the expense of the other stakeholder. In contrast, co-opetition—a term coined in 1996 in the book of the same name—succeeds when there is a congruence of interests that mutually benefits collaborators, even when they compete in other spheres.

You’ve Got Mail

One example is the co-opetition between the United States Post Office and United Parcel Service. The strength of the Post Office is coverage of “the last mile” to a recipient’s door. UPS has a national distribution system that provides superior logistics. Just as it is more economical for UPS to pick up a package from a warehouse and ship it across its delivery network, it is more economical for the Post Office to deliver that package to its final destination. In addition, customers of participating retailers can conveniently return UPS delivered merchandise by dropping it off at a Post Office mailbox. The two package delivery competitors get to share higher profits by avoiding higher costs of operation they otherwise would have incurred had they operated separately. And packages are shipped faster, providing higher value to both the shipper and the recipient.

Milking It

Brian Wiedemann, owner of George Bowers Grocery in Staunton, Virginia, works with two other local businesses to acquire organic milk for customers. “We work with our local gelato shop and a natural foods grocer to meet the purchase and delivery minimums required for a small-scale dairy farm. Distribution is one of the trickiest parts of small-scale agriculture, so this group purchase allows our respective businesses to grow while also serving our customers.”

Growth of the Amazon Jungle

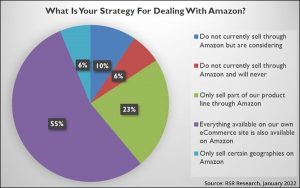

Rightly or wrongly, Amazon is widely viewed as the Internet juggernaut responsible for the decline if not demise of small businesses that can’t compete with its size and scope. Yet Amazon’s Marketplace provides these very same small competitors with a widely regarded eCommerce portal in return for a small percentage cut of their online sales.

This not only provides a revenue stream for Amazon that has consistently grown over the years, but contributes further profitability by allowing it to amortize software development and other operating expenses over a greater number of items.

These small businesses can’t compete directly with a giant company like Amazon, but by cooperating can improve their profits and long-term sustainability. Moreover, the ultimate winners are consumers who get greater choices and more competitive pricing.

(356)

Report Post