By Sam Becker

Don’t bend, don’t break: That may be the winning strategy to defeat office bullies, according to new research.

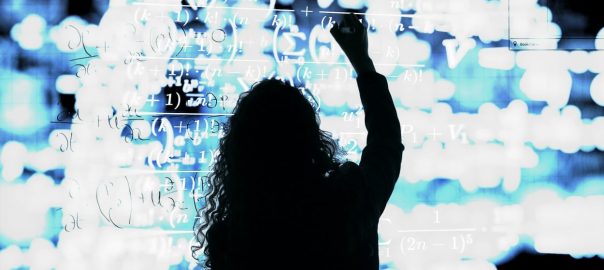

Researchers from Dartmouth College have found that there may be some surprising ways to fight back against workplace bullies, uncovering an “Achilles’ heel” that can help equalize the playing—or working—field. It’s all about utilizing the dynamics of game theory, and the underlying mathematics of optimized competitive strategies.

Game theory is a branch of mathematical and economic research concerning the interactions between parties in some sort of competition—the players in a poker game, for example. There can be strategies at play that one party may use against the other to reach a desired outcome. Typically, the two responses are either to cooperate or defect. But when “extortionists” control situations in a given scenario (such as an office bully), other parties can use “zero-determinant (ZD) strategies” to fight back.

In effect, the Dartmouth study finds that when you’re up against a “fixed extortioner” (i.e., a bully), refusing to submit to his or her demands may be the best strategy, and may result in the extortioner coming out a loser in the exchange. This “unbending strategy,” as it’s called in the study, involves a refusal to cooperate with the bully.

“Unbending players who choose not to be extorted can resist by refusing to fully cooperate. They also give up part of their own payoff, but the extortioner loses even more,” said Xingru Chen, one of the paper’s authors, and an assistant professor at the Beijing University of Posts and Telecommunications, in a Dartmouth release.

“Our work shows that when an extortioner is faced with an unbending player, their best response is to offer a fair split, thereby guaranteeing an equal payoff for both parties,” she said. “In other words, fairness and cooperation can be cultivated and enforced by unbending players.”

Essentially, the study finds that fairer outcomes can be effectively forced by players in interaction by flat-out refusing to play the game. This may have been seen recently in the American political sphere during the recent debt ceiling negotiations—two parties, each hoping for different outcomes, attempted to play the “unbending” card (the White House, in particular) to gain the concessions they wanted. Neither was completely successful, but at the onset, the strategies appeared similar.

Other real-world examples were spelled out by the paper’s senior author, Feng Fu. “Consider the dynamics of power between dominant entities such as Donald Trump and the lack of unbending from the Republican Party, or, on the other hand, the military and political resistance to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine that has helped counteract incredible asymmetry,” Fu said in the Dartmouth release. “These results can be applied to real-world situations, from social equity and fair pay to developing systems that promote cooperation among AI agents, such as autonomous driving.”

As for how workers can utilize this research in the workplace? In the simplest terms, refusing to give in to an office bully’s power plays or initial attempts at enforcing their will on others is a good place to start. By refusing to bend to the “extortionist,” workers can effectively reset the terms of engagement by holding fast. There’s no guarantee that they’ll get the outcome they want, of course, but it may help some people who are used to being steamrolled by managers, or others, reclaim a bit of power in the workplace.

(13)