You might assume that humans buy products because of what they are, but the truth is that we often buy things because of where they are. For example, items on store shelves that are at eye level tend to be purchased more than items on less visible shelves.

In the best-selling book Nudge, authors Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein explain a variety of ways that our everyday decisions are shaped by the world around us. The effect that eye-level shelves have on our purchase habits is just one example.

Here’s another:

The ends of aisles are money-making machines for retailers. According to data cited by the New York Times, 45 percent of Coca-Cola sales come specifically from end-of-the-aisle racks. (1)

Here’s why this is important:

Something has to go on the shelf at eye level. Something has to be placed on the rack at the end of the aisle. Something must be the default choice. Something must be the option with the most visibility and prominence. This is true not just in stores, but in nearly every area of our lives. There are default choices in your office and in your car, in your kitchen and in your living room.

My argument is this:

If you optimize the default decisions in your life, rather than accepting whatever is handed to you, then it will be easier to live a better life.

Let’s talk about how to do that right now.

Design for Default

Although most of us have the freedom to make a wide range of choices at any given moment, we often make decisions based on the environment we find ourselves in.

For example, if I wanted to do so, I could drink a beer as I write this article. However, I am currently sitting at my desk with a glass of water next to me. There are no beers in sight. Although I possess the capability to get up, walk to my car, drive to the store, and buy a beer, I probably won’t because I surrounded by easier alternatives—namely, drinking water. In this case, taking a sip of water is the default decision, the easy decision.

Consider how your default decisions are designed throughout your personal and professional life. For example:

- If you sleep with your phone next to your bed, then checking social media and email as soon as you wake up is likely to be the default decision.

- If you walk into your living room and your couches and chairs all face the television, then watching television is likely to be the default decision.

- If you keep alcohol in your kitchen, then drinking consistently is more likely to be the default decision.

Of course, defaults can be positive as well.

- If you keep a dumbbell next to your desk at work, then pumping out some quick curls is more likely to be the default decision.

- If you keep a water bottle with you throughout the day, then drinking water rather than soda is more likely to be the default decision.

- If you place floss in a visible location (like next to your toothbrush), then flossing is more likely to be the default decision.

Researchers have referred to the impact that environmental defaults can have on our decision making as choice architecture. It is important to realize that you can be the architect of your choices. You can design for default. (2)

How to Optimize Your Default Decisions

Here are a few strategies I have found useful when trying to design better default decisions into my life:

Simplicity. It is hard to focus on the signal when you’re constantly surrounded by noise. It is more difficult to eat healthy when your kitchen is filled with junk food. It is more difficult to focus on reading a blog post when you have 10 tabs open in your browser. It is more difficult to accomplish your most important task when you fall into the myth of multitasking. When in doubt, eliminate options.

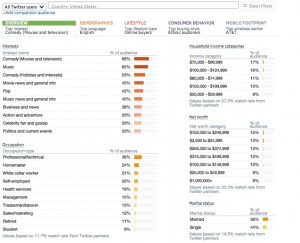

Visual Cues. In the supermarket, placing items on shelves at eye level makes them more visual and more likely to be purchased. Outside of the supermarket, you can use visual cues like the Paper Clip Method or the Seinfeld Strategy to create an environment that visually nudges your actions in the right direction.

Opt-Out vs. Opt-In. There is a famous organ donation study that revealed how multiple European countries skyrocketed their organ donation rates: they required citizens to opt-out of donating rather than opt-in to donating. You can do something similar in your life by opting your future self into better habits ahead of time. For example, you could schedule your yoga session for next week while you are feeling motivated today. When your workout rolls around, you have to justify opting-out rather than motivating yourself to opt-in.

Designing for default comes down to a very simple premise: shift your environment so that the good behaviors are easier and the bad behaviors are harder.

Designed For You vs. Designed By You

Default choices are not inherently bad, but the entire world was not designed with your goals in mind. In fact, many companies have goals that directly compete with yours (a food company may want you to buy their bag of chips, while you want to lose weight). For this reason, you should be wary of accepting every default as if it is supposed to be the optimal choice.

I have found more success by living a life that I design rather than accepting the standard one that has been handed to me. Question everything. You need to alter, tweak, and shift your environment until it matches what you want out of life.

Yes, the world around you shapes your habits and choices, but there is something important to realize: someone had to shape that world in the first place. Now, that someone can be you.

This article was originally published on JamesClear.com.

- This data comes from the article, “Nudged to the Produce Aisle by a Look in the Mirror.”

- Thanks to my friend Christine Lai for originally tossing out the term “design for default” in a conversation I had with her.

(80)

Report Post