— January 21, 2019

“You gotta flex. You gotta look good, bro.” – Kiari “Offset” Cephus

Scrum stands on the three legs of transparency, inspection, and adaptation. Of these, transparency can arguably be said to come first. Unless a situation is made clear it cannot be inspected, and any consequent adaptation arising therefrom is likely to prove futile.

Clarity over the amount of work which is thought to remain for a product is one example of transparency, and it is essential to have a definitive Product Backlog which provides it. In Scrum, the contents of the backlog will need to be refined, estimated, planned into Sprints, and increments of work satisfying those requirements delivered in each iteration. Projective practices may then be used — based on the empirical evidence of value honestly delivered — to determine whether or not any future plans for the product are realistic. Transparency is indeed essential in Scrum, and if an implementation of the framework is to succeed, it must be paired with a culture of discipline and rigor.

Achieving this standard is hard. Many Scrum practitioners will have experienced situations where a struggling Product Owner has wanted a team to action ad-hoc work immediately. He or she may have claimed that the work was too urgent to be refined and planned into a future Sprint. In the name of a supposedly greater agility, it may have vaulted over the Product Backlog and made little or no contact with it at all. Indeed, the rules of Scrum are all too frequently dispensed with in the heat of battle. Agility is very often lost to a reactive mode of fire-fighting, and perhaps just as often confused and conflated with it. Any work which is planned or in progress becomes obscured, and the amount which truly remains becomes indeterminate. Transparency is the first casualty of a weakened Scrum implementation.

Of course, it’s important to recognize that urgent and unforeseen work does genuinely arise, and must therefore genuinely be dealt with. Unless technical debt is kept under careful control, for example, a product is likely to become unstable and its defect rate will escalate. Scrupulous attention to the Definition of Done is instrumental in reducing this particular problem, as is inspecting and adapting frequently. Nevertheless, “emergencies” of one sort or another can still happen. Scrum is optimized for complex product development where there are at least some unknowns. If the length of a Sprint is decided with care, and if a release-quality Definition of Done is diligently observed, then the risk of ad-hoc work arising can only be minimized. What a team cannot do is to eliminate that risk entirely.

Some Development Teams are tempted to reserve a buffer, each Sprint, to accommodate any urgent and unplanned work they are expected to do. For example, they may perhaps estimate that ten or twenty percent of their time should be reserved to cope with ad-hoc or emergency requests. They are perfectly entitled to adopt this way-of-working, given that major outages or other P-level incidents must be expedited and handled.

Yet what this buffer effectively does is to formally reduce transparency. Any work which is undertaken in that buffer, by definition, cannot be foreseen or planned for. In fact, should no emergency happen, the time so reserved might not be needed at all. An ad-hoc planning session to bring work forward from the Product Backlog might then be in order.

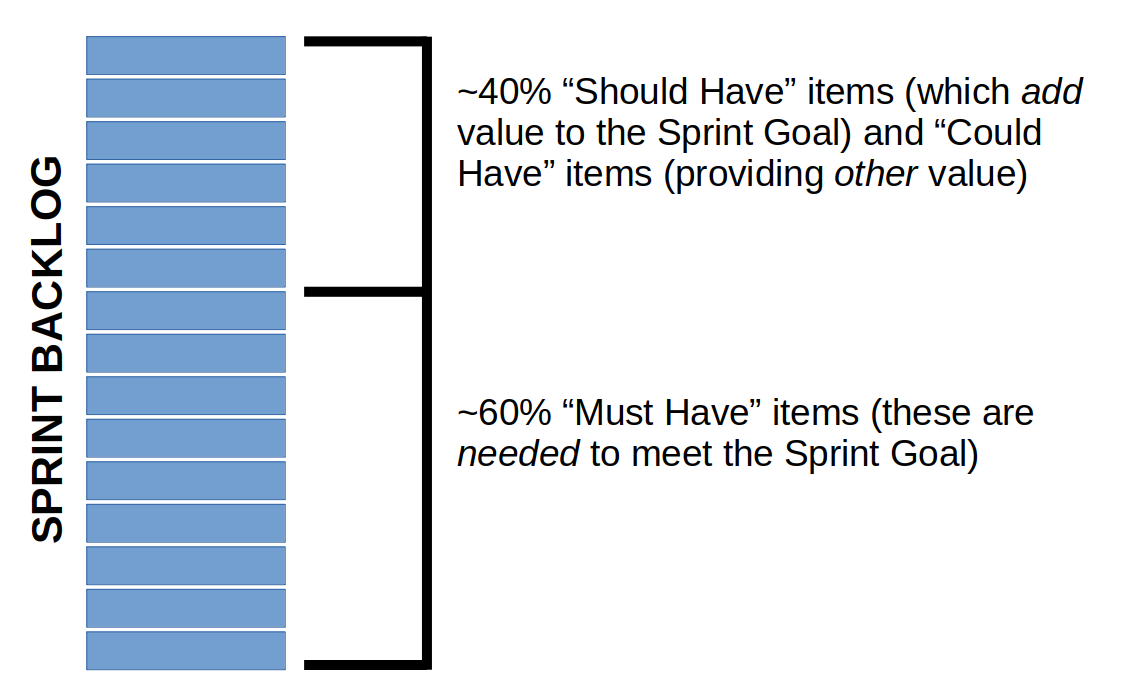

Another approach is to plan a certain amount of work into the Sprint Backlog which — while enhancing the value provided during the Sprint — is not absolutely critical to the Sprint Goal. The practice of valuing work in terms of Must Have, Should Have, and Could Have requirements supports the mechanism. In this technique, only Must Have items are considered essential to the Goal, and they may only contribute to a certain proportion of the backlog — typically 60%. The remaining 40% or so of the backlog is made up of Should Have requirements which add value to the Goal but are not critical to it, and Could Have requirements not necessarily aligned to the Goal but which nevertheless provide value.

This scheme allows for scope to flex in response to unforeseen events of various kinds. Unessential work (Could Haves, and then if necessary Should Haves) may be traded out of scope in an emergency, while the Goal itself remains achievable and intact. In effect scope is used as a buffer. In agile practice it is matters of scope, rather than time or quality, which indicate where a team’s contingency ought to lie.

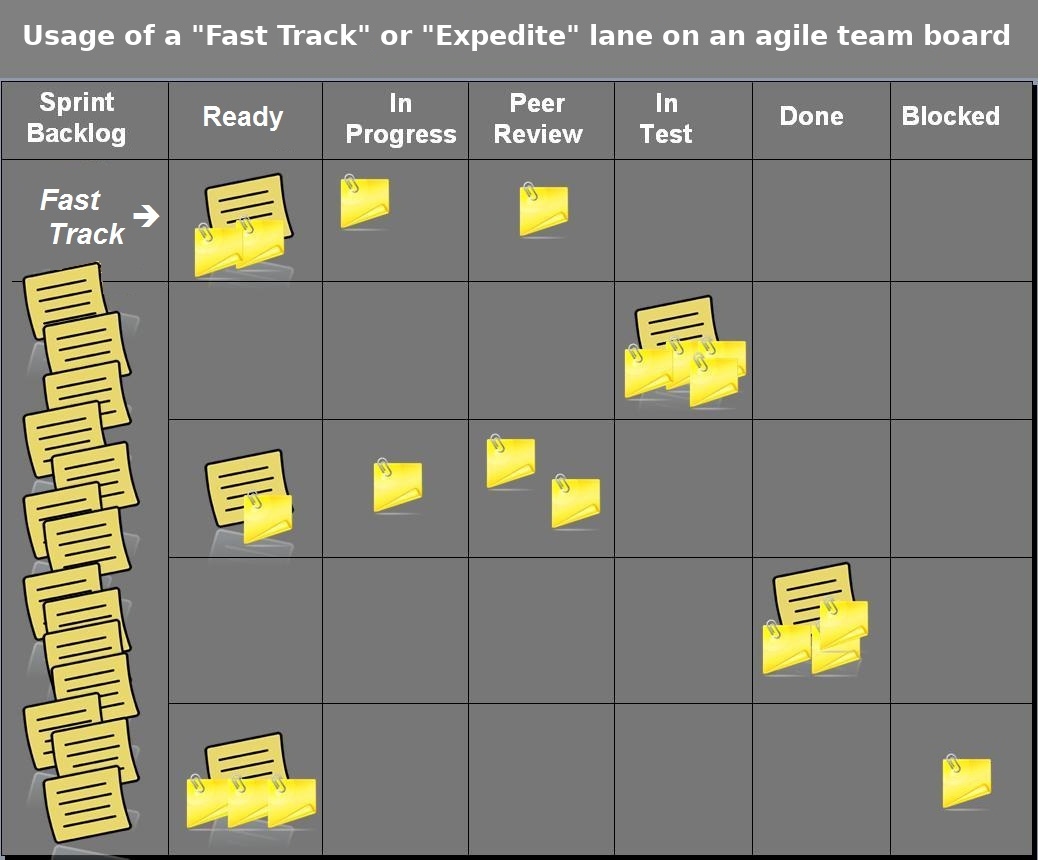

Supporting different qualities of service for different types of work can provide much-needed transparency over the issues. For example, a team may have an “expedite” lane on their team board for unplanned urgent items. When expedition is requested, such as when a critical issue arises, the team will decide whether or not existing work can be replanned to accommodate it without compromising the Goal. Informed decisions about the viability of the Sprint can then be made accordingly.

Bear in mind that no-one can force work onto a Development Team. If a Product Owner requests that an unplanned, urgent, and critical piece of work be actioned — but there is insufficient work for the team to trade out of scope while preserving the committed Goal — then the value of continuing with the Sprint may have to be reconsidered. Using clear “scope flex” mechanisms and protocols to absorb such risk helps to reduce the chance of a Sprint having to be canceled.

Business & Finance Articles on Business 2 Community

(86)