By Scott Raynor, Published October 14, 2014

A look at the different understandings of what constitutes as viral content exposes the rare nature of what ultimately drives content to go viral. What does it actually mean to go viral? We hear a lot about what increases the likelihood of making content “go viral,” why certain blog posts and videos have gone viral, but there’s little known about what actually factors into virality. After a review of research on the subject, definitions have emerged from academics, biologists and one large social media giant. It suggests a more nuanced understanding of how information is spread on the Internet and the surprising rarity of viral content. See also: These Emotions Might Make Your Written Content Go Viral

Going Viral as Defined by Biology

A virus is a microscopic organism that requires a host body to survive, replicate and spread. It’s commonly spread through what’s called horizontal transmission, which is when a disease spreads within the same species through physical contact or airborne transmission. When a virus “goes viral,” it spreads from the original source to another, and another and another — capable of being dispersed far from the original source. According to research from the University of Arizona, a single contaminated doorknob in a office building — infected with a tracer virus similar to Norovirus — spreads to as much as 60 percent of surfaces in two to four hours. Anyone who’s published a hit post knows its clicks and social media impressions can seem to accelerate just as fast. This basic model of how viruses spread has actually informed some recent research on the subject —which actually complicates our understanding of Internet virality.

Structural Virality

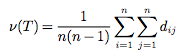

Mircrosoft Research and Stanford University researchers recently applied the biological definition of virality to the spread of approximately one billion events on Twitter — that is, tweets and retweets. The researchers (led by Sharad Goel) came up with their own definition of virality. It’s called structural virality; it involves math and it looks like this:

It’s essentially the average distance between each person that spreads a piece of content, from the creator to each and every person that clicks a share button. That means an article of a bizarre or shocking crime created by Yahoo News that receives a million hits — but is rarely shared — isn’t really viral at all since there’s only one person (Yahoo News) that shared the story. Meanwhile, a modestly trafficked BuzzFeed quiz on bookish introverts that’s shared among thousands of like-minded bookish introverts earns significantly more virality.

Going Viral as Defined by Facebook

An update to Facebook’s insights — its page to help Facebook page owners track the performance analytics — introduced the option to see the “viral reach” of each post. When Facebook introduced it, the social media giant defined it as the the number of people who created a story from a post on your Facebook page, divided by the number of “unique people” who have seen that original post. See also: 5 Ways to Make Your Content More Original That means if you publish a post on Facebook and it’s passed in front of 9,000 unique viewers — but only 90 shared it with their friends — it has a virality of only 1 percent. This understanding of virality is specific to the structure of Facebook, but it helps emphasize the importance of interaction when measuring virality.

When Going Viral Isn’t Actually Viral

As we’ve seen above, narrowing down a real definition of viral is incredibly difficult. Partially, this is due to the new nature of this field of study, but the biggest challenge may be the attempt to measure events that are too rare to accurately analyze. Much of what we think is viral isn’t. In their research, Goel points out that thechances of content going truly viral in their dataset was one in a million. Approximately 99 percent of tweets ended either with retweets from immediate followers or no retweets at all. This suggests the rich conversations we like to think are happening around our content may be somewhat one-sided. Much the same is true with Facebook as well, according to an article from “digital marketing advisors” Convince and Convert. In looking at a client’s Facebook page with over 500,000 followers, they found that the “organic reach” — total number of eyes on a post — was six to 12 times higher than the”viral reach,” which accounted for only about 1.2 percent of traffic.

What’s Really Happening?

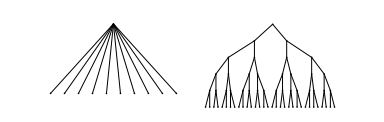

If content isn’t as viral as we might think, then how does it really spread? More often than not, Goel’s research suggests the spread of information is more similar to a broadcast of the Super Bowl than a fast-moving virus. The difference is that in broadcasting, a message is sent to people directly — whereas a viral spread relies on spreading via word of mouth. The difference looks like this:

For every 10 tweets in the research study, Goel and his team found only an average of three retweets. This means there’s less person-to-person sharing and more traditional “broadcasting” than we might imagine. It may be that, despite the rapid change the Internet has brought to our communication, the spread of content might be less diverse than the days before viral web content was even possible. What are your thoughts on the debate of viral content? Share them with us in the comments section below.

Images: The structural virality of online diffusion. Authors: Sharad Goel, Ashton Anderson, Jake Hofman and Duncan J. Watts.

Business Articles | Business 2 Community

(458)

Report Post