In October 2020, as it became clear COVID-19 wasn’t going anywhere anytime soon, Dropbox made a big bet. Rather than continuing with a temporary remote-work policy and postponing longer-term decisions, the company declared it was going virtual-first. Henceforth, employees could work from anywhere and—with some coordination of collaboration hours—on their own schedules. The company argued that doing so wouldn’t hinder its ability to build products and run its business. Actually, it believed the move would make it easier to understand what customers wanted in an age when collaboration would be more distributed than ever.

Three years later, enough normalcy has returned to the world that Dropbox is holding a conference called Work in Progress: Perspectives today in New York City. It’s the first in-person edition since the before times, combining product updates with more open-ended conversations about where work is going as AI seems to be on the cusp of fundamentally transforming it.

As the event approached, I spoke with cofounder and CEO Drew Houston about what’s new with Dropbox the product and Dropbox the company. We were both using Zoom from the comfort of our own homes, which was a sign of changing times in itself. The last time we talked, in 2019, we met in a music-themed room at the company’s palatial headquarters in San Francisco—one of the lavish legacies it shed by embracing virtual work.

Looking back, Houston doesn’t seem haunted by regret over the era when Dropbox signed the biggest commercial real estate lease in San Francisco history and had a cafeteria so remarkable that the urban legend it had earned a Michelin star seemed plausible. “I wouldn’t change a lot,” he maintains. “I mean, I think we got a little carried away. We maybe solved a little bit too much for our comforts.” But he says that the company’s 2020 gamble on virtual collaboration has paid off in a big way. And he’s quick to connect the dots between its move away from brick-and-mortar teamwork and its ability to leverage AI to best advantage in its products.

“We’re using Dropbox as a lab,” he says. “In a world where everybody’s relocated to the cloud and working in screens instead of offices, and where we have this silicon brain that’s a great compliment to our human brain.”

AI, Dropbox style

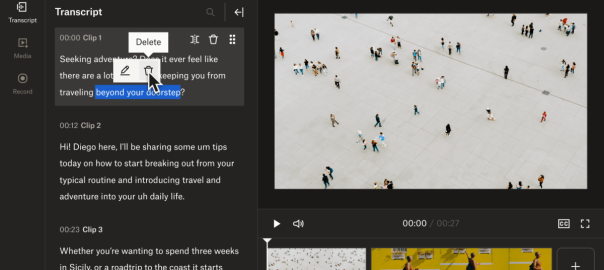

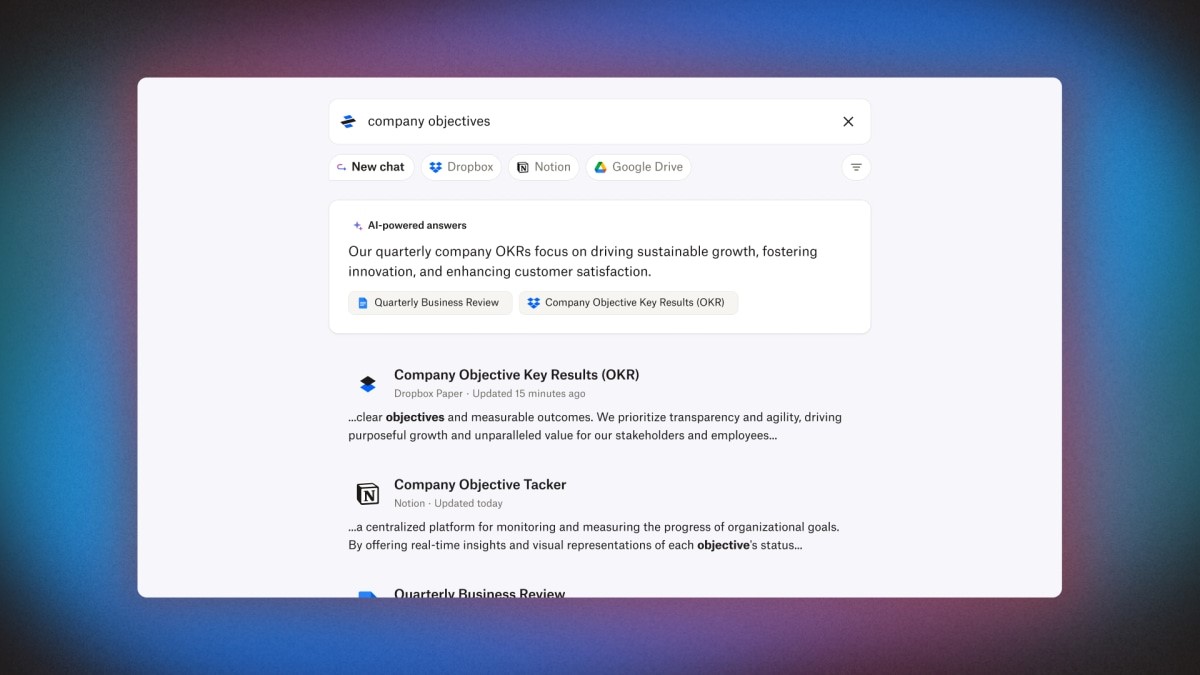

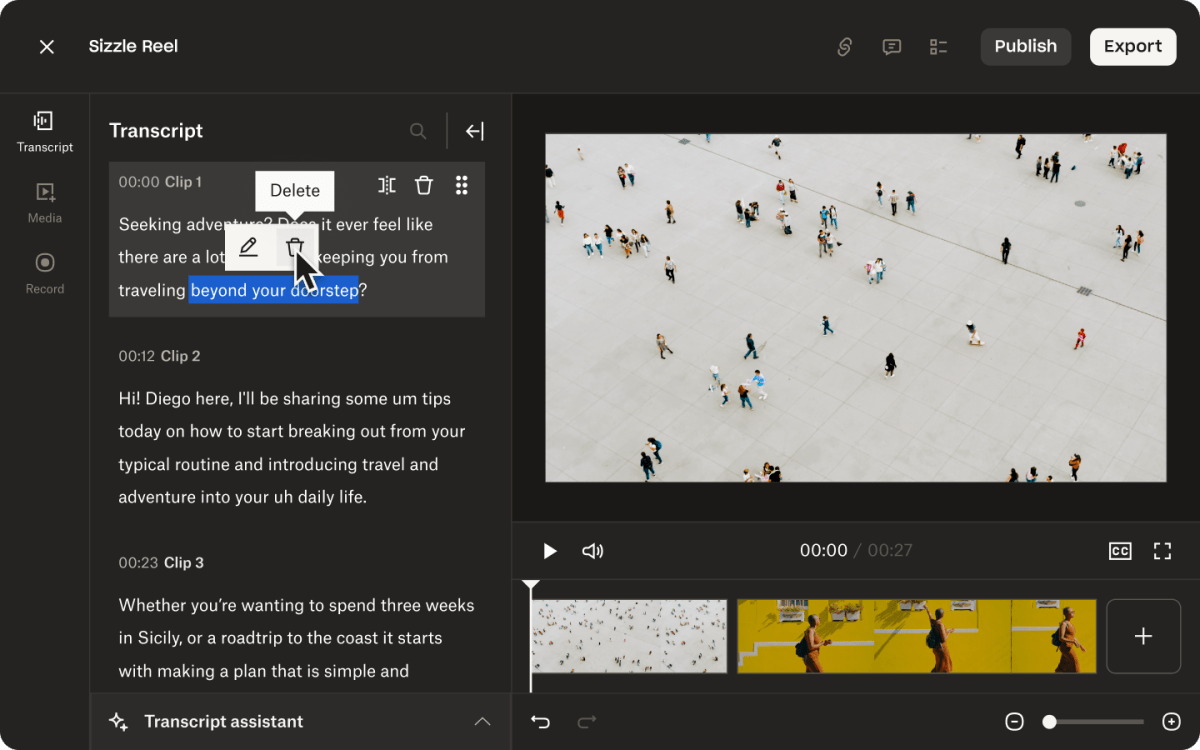

At its conference, Dropbox is showing off several uses of AI across its portfolio of products for wrangling digital content, none of which have yet reached general availability. Dropbox Dash, an AI-powered universal search tool is entering public beta: It can scour Microsoft 365 (née Office), Google Workspace, Salesforce, Notion, and numerous other apps along with Dropbox itself. Dropbox AI, which soups up Dropbox searches with features such as summarization and natural-language queries (“show me photos from my photoshoot (October 22, 2023)”), is still in alpha but rolling out to more users. Also in alpha: Dropbox Studio, a new video editing/posting tool with AI-infused capabilities such as the ability to slice frames out of a video by deleting blocks of text in a transcript.

Of course, it would be bizarre if Dropbox weren’t using AI to reimagine broad swaths of its products. Everyone else—from competitors in the company’s own Zip Code (Box) to productivity’s kingpins (Microsoft, Google)—is also doing it. Some of what Dropbox is building, such as summarization features, feel like they’ll soon be regarded as necessities, not breakthroughs. But Houston says there’s plenty of opportunity for the company to distinguish itself even as AI becomes table stakes.

It’s not because Dropbox has created its own core AI from scratch. Indeed, it’s relying on some of the same technological underpinnings as others, including two major large language models: OpenAI’s GPT and Meta’s Llama. “The LLM is just one piece of the puzzle,” says Houston. “It’s the most shiny piece. It’s like the alien artifact everybody’s poking at and loves to talk about. But that’s the tip of an iceberg where there’s a lot of engineering you need under the waterline, which in many ways is a lot more of the technical challenge.” Those problems, he says, are reminiscent of the ones Dropbox tackled in its early days, when it was working to make cloud storage simple, scalable, reliable, and economical.

With AI, Dropbox is dealing with smaller, better-defined repositories of data than a know-everything service such as ChatGPT or Bing Chat must process. That might make it less likely to make up stuff that sounds eerily real. But applying AI in Dropbox’s context opens up all sorts of issues of its own. “If I unshare a document with you, for example, [we] need the LLM to forget it immediately,” Houston says. “And we don’t really know how to make LLMs forget stuff.”

Then there’s the fact that Dropbox initially became popular by taking a gnarly productivity challenge—getting access to all your files on all your devices—and making it work so well that it was practically invisible. That’s still what many people want from the service. And as the company has expanded its ambitions, it’s sometimes ticked off longtime loyalists, particularly when individuals were confronted with features aimed at business customers.

Exploring new territory without overcomplicating the essentials “is such a hard design challenge, and one where we’ve stubbed our toe in the past,” acknowledges Houston. This time around, the company is redoubling its effort to introduce new features in ways that don’t feel like an imposition to anyone. For instance, the Dropbox Dash universal search tool is a standalone product, not part of the familiar file-syncing experience.

“A lot of the basic, fundamental principles around making things simple and really easy to use, kind of the soul of Dropbox, we hope don’t change too much,” says Houston. “But there’s a new, bigger canvas we’re painting on.”

(Mostly) virtual

As for how Dropbox the company is doing, it certainly hasn’t been immune to the shock waves roiling the tech industry. In April, it laid off 16 percent of its workforce, a move Houston attributed at the time in part to the need to redeploy resources toward new AI initiatives. But he touts the company’s virtual-first experiment as a model for other organizations that are still figuring out what work should look like in 2023 and beyond.

That many well-known tech companies continue to struggle with that question is clear from the steady stream of news stories involving managers trying to corral recalcitrant, far-flung employees back into physical offices. Over the summer, for instance, there were reports that Google was monitoring whether workers were badging in and touting $99 specials at an on-campus hotel. Meanwhile, Meta’s attempts to manage its new hybrid policy were deemed “a mess” by one employee quoted in a Fortune story.

If anything, the ongoing disconnect between the industry’s top brass and its rank and file has reinforced Houston’s feeling that Dropbox made the right decision when it demoted traditional face time to an occasional element of its approach to collaboration—typically a few days each quarter.

“Our belief is that this sort of default awkward compromise of, ‘Okay, we’ll do three days [a week] in the office,’ is really the worst of both worlds,” he says. “Certainly, some companies are going to be able to make that work. But you’re asking a lot more of your employees . . . because people spread out during COVID. In a lot of cases, folks were authorized to move away, and now [management] is saying, ‘Never mind, come back.’” He calls that backtracking “a crazy rug pull.”

Instead of obsessing over the quantity of in-person interaction, Dropbox focused on its quality. “What we find is, if . . . you think of the most memorable moments in your career, it’s usually not in a windowless conference room on a random Thursday afternoon, ” says Houston. “It’s when you’re all together and present somewhere nice.”

At first, the company envisioned doing this periodic collaboration in spaces it operated. It later decided to sublet even more of its physical footprint and convene staffers at retreat-like periodic gatherings in interesting places. When I asked Houston for an example or two of where such get-togethers were held, he didn’t mention any specific destinations: “In the Bay Area, we’re pretty lucky—there’s a lot of these places you can go, kind of in any direction.”

Today, 70% of new recruits cite the virtual-first policy as a key reason why they’re joining Dropbox. Last month, the company ranked #1 in Glassdoor’s list of the top tech companies for culture and values: “That doesn’t mean we’re perfect . . . but we’ve shown at least you can still have a functioning and vibrant culture in these environments,” says Houston.

When Dropbox was new to virtual work, it studied the techniques of companies that had made it part of their DNA long before COVID-19 came along, such as GitLab and Automattic. Now it’s confident enough in its learnings that it shares them in an open-source virtual first toolkit, though Houston isn’t ready to disclose everything it’s trying: “We’re experimenting with lots of different concepts that we haven’t released or talked about yet.”

As the name of Dropbox’s conference indicates, the future of collaboration is unquestionably a work in progress. Regardless, Houston argues that looking backward is not a viable strategy—even if you’re a CEO with the theoretical power to decree whatever policies you choose.

“You can’t go back to 2019,” he says. “Once people have a taste of that flexibility, they’re not going to give it back.”

(19)

Report Post