How IBM invented the smartphone, then abandoned it

1994’s Simon was the first rough draft of a device that would change the world. But it was also a dead end.

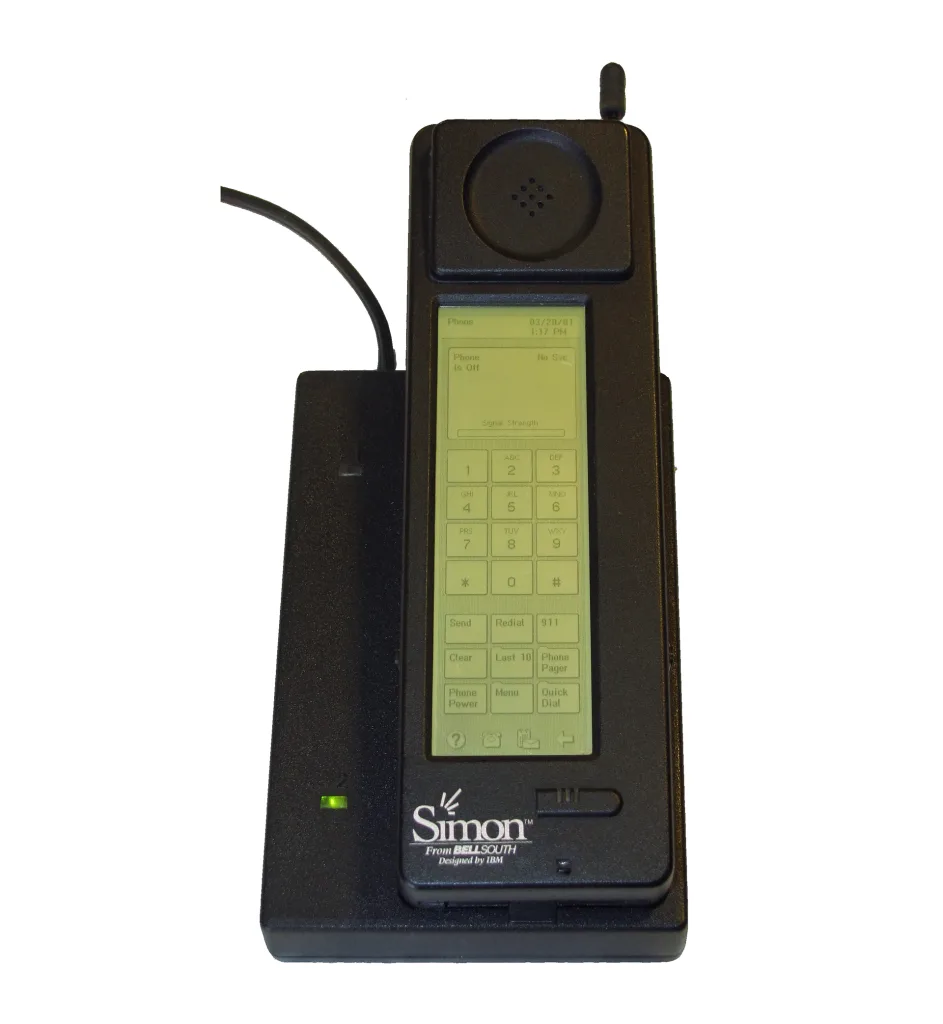

In October 1994, I reviewed a new gizmo for InfoWorld, a prominent tech newsweekly. The device in question—the result of a collaboration between IBM and wireless carrier BellSouth—was a mobile phone known as Simon. Like all 1994 cellphones, it was a brick-like behemoth. But the reason InfoWorld cared about it was because it was also a handheld computer. Its tiny touchscreen interface let you access and send email, manage your calendar, take notes, and—whoop-de-doo!—send faxes.

I spent much of my story detailing Simon’s many shortcomings, from its unwieldy touchscreen QWERTY keyboard (which required you to rotate the phone 90 degrees to type) to its sluggish performance (which sometimes left you waiting 10 seconds for anything to happen). However, I was open-minded enough to declare the hybrid phone/personal digital assistant “unique” and concluded that “adventurous mobile workers” might find it worthwhile.

I just wish I’d been prescient enough to realize that it was the first product in a new category that would someday eclipse even the PC in epoch-shifting significance: the smartphone.

1994 was like that. On multiple fronts, personal technology was evolving very quickly. Sometimes the payoff was obvious and immediate; in other instances, it would take years or even decades to play out. And in still additional cases, developments that seemed historic didn’t lead much of anywhere.

Overall, 1994 was just plain interesting, in ways that were rewarding at the time and worth remembering today. So recently, when we were discussing possible themes for a package of history-minded Fast Company stories, we decided to look at some of the products, technologies, and machinations that defined the year.

As I write, we’re midway through our 1994 Week and have published four stories:

- My look at the year’s hottest new medium—not the still-emerging World Wide Web, but CD-ROMs.

- David Zipper’s history of GM’s EV1—a pioneering electric car that someone once said might have rendered Tesla irrelevant if GM had stuck with it. (That someone was Elon Musk.)

- Chris Morris on why 1994 was the year the video game business grew up, with a little prodding from publicity-hungry senators.

- Jared Newman’s report on what it’s like to use a prerelease version of Netscape Navigator—once the world’s most popular browser—to surf the web in 2004.

Two more 1994 Week stories are yet to come, from my colleagues Jessica Bursztynsky and Alex Pasternack. I’ll leave the topics as surprises; they, and the rest of our lineup, will be available here.

So much happened in 1994 that we could have run three times the number of stories without running out of fodder. For example, Iomega’s Zip disk, the QR code, the web banner ad, and the browser cookie all debuted that year. In an early e-commerce breakthrough, you could order a pizza from your web browser, at least if you lived within delivery range of one particular Pizza Hut in Santa Cruz, California. Intel discovered that its Pentium chip had an obscure malfunction that (very occasionally) led to math glitches—one of the first instances of faulty technology making headlines. And Jeff Bezos founded a company called Cadabra, which he rechristened Amazon long before it started shipping books to customers the following year.

I could go on. But instead, I’ll return to the Simon phone. It represented the commercialization of a tech demo created by IBMer Frank Canova, first shown publicly at the COMDEX trade show in Las Vegas on November 24, 1992. (I attended the conference and wish I could say I remember seeing Canova’s prototype, which was known as “Sweetspot.”) IBM took the better part of two years to turn the idea into a working product, which was delayed by software bugs and finally went on sale at BellSouth dealers in August 1994. (For more details on all this—including some internal IBM documents—I direct you to this nifty Simon history site.)

At the time, cellphones of any kind hadn’t achieved ubiquity, at least in the U.S.; even the following year, I still remember being startled by how many passersby I saw using them during a visit to London. Turning one into a networked computing device was wildly ambitious. IBM had to figure out a user interface that would fit onto Simon’s tiny-but-tall display. It had to decide which features were essential (a calendar made the grade, but a spreadsheet did not). It had to shuttle email over a 1G network, well before email services were designed with wireless communications in mind. The company even came up with a primordial form of predictive typing to help facilitate text input.

IBM did punt on certain aspects of the project. Rereading my review, I see that I dinged the Simon device for lacking cut-and-paste functionality, something that struck me as table stakes for any computing platform. What I didn’t know then was even the iPhone would do without that convenience for its first two years on the market.

Evaluating the device for the business-minded InfoWorld, I wasn’t expected to give points for sheer audacity. Nor did we cut IBM and BellSouth any slack for the severe constraints they had to contend with. Back then, I didn’t know that later smartphones would have high-resolution color screens, PC-class processors and storage, and more cellular bandwidth than they knew what to do with. Did I mention multiple cameras, sensors such as GPS, and all the other features we now take for granted?

BellSouth reportedly sold 50,000 Simons before discontinuing the phone in February 1995. By modern standards, that might sound like failure. (In 2023, according to IDC data, Apple sold that many iPhones every couple of hours.) Still, given the bleeding-edge nature of the $899 device, it doesn’t feel like abject failure to me. Sadly, there would be no Simon II: IBM began work on a smaller second-generation model, code-named “Neon,” but abandoned it before release.

It’s obvious now that several generations of Simon would have been necessary to get to something with the potential to be a breakout hit. It’s hard to imagine IBM—which even backed out of the PC business it helped create—making that long-term investment in a new hardware category.

Instead, two other companies that rose to prominence before the 1990s were over prepped the world for the smartphone revolution to come. One was Palm, whose PalmPilot personal digital assistant was pocketable, affordable, and an ace at handling productivity tasks that could be done well at the time, such as syncing appointments and contacts with a desktop PC. The other was BlackBerry, which built email into a pager-style gadget with a QWERTY keyboard that was astoundingly usable given its dinky size. Buoyed by technological advances that occurred after the Simon’s premature demise, both companies ended up making popular smartphones before being washed away by the iPhone.

There’s plenty of recognizable PalmPilot and BlackBerry DNA in modern iPhones and Android phones. The Simon, meanwhile, didn’t leave nearly as distinct an imprint. Then again, its inventor, Frank Canova, certainly did, going on to engineer some of Palm’s seminal devices. The phone he designed for IBM was too early to the smartphone party to succeed. But I’m sure glad I got to try it for myself then—and am pleased to have finally had an excuse to revisit it here in the 21st century.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

(8)

Report Post