“What is beautiful is good,” the saying goes.

This saying stems from a belief that attractiveness correlates to other good qualities. In a phrase, attractiveness is a Halo Effect.

Of course, you can see that on the surface, the logic in that saying is flawed. What’s beautiful has nothing to do with what is good. But we still conflate overall perception and individual traits, making our judgment of things less accurate than we believe.

What is the Halo Effect?

The Halo Effect is a cognitive bias where one trait of someone/something influences how you feel about other, unrelated traits.

As I mentioned, one of the most popular examples of this effect is in attractiveness. We perceive good-looking people to be more intelligent, more successful and more popular. More attractive political candidates tend to be perceived as more knowledgeable, regardless of their level of knowledge.

One study found that subjects were more lenient when sentencing attractive individuals than unattractive ones, even though exactly the same crime was committed.

It works for things other than attractiveness, though.

Edward Thorndike first coined the term in a 1920 paper, where researchers asked commanding officers in the military to evaluate a variety of qualities in their subordinate soldiers. These characteristics included such things as leadership, physical appearance, intelligence, loyalty, and dependability.

They found that high ratings of a particular quality consistently correlated with high ratings of other characteristics, and negative ratings of a specific quality also led to lower ratings of other characteristics.

The research goes on and on, in all sorts of different areas and industries, but it all spells out a simple truth: we don’t evaluate things as they objectively are, but through lenses that we may not even be aware of.

The Halo Effect has a wide breadth of uses, reaching areas like management, design, copywriting, advertising, and of course, A/B testing and conversion optimization strategy.

Halo Effect as a Persuasion Strategy

Marketers and advertisers have been using the Halo Effect for a long time, whether they were conscious of it or not.

They knew that by associating a product with something (or someone) attractive, they could raise the perceived value of the product as well.

In business and as a persuasion strategy, we consistently see this strategy employed in a few ways:

- Celebrity endorsements (or appeal to authority)

- The use of beautiful people

- Beautiful design (or making a good first impression)

- Broken features lower overall perception

- Corporate (big) names

- The rising tide effect of products and companies

Celebrity Endorsements

Celebrity (or authority) endorsements are incredibly common, not just online, but in the history of marketing. The logic goes, “if X important person used Y product, it must be amazing.”

Thing is, if the allure of the celebrity is strong enough, there doesn’t even need to be a strong correlation between the celebrity and the product (though this can sometimes lead to a “Vampire Effect,” where tools used creating attention end up pulling too much of it away from the actual product).

This form of the Halo Effect is really a highly visible type of social proof. As Jeremy Smith wrote on Neuroscience Marketing, “You can use the halo effect by associating authoritative people with your product or service. E.g., “Steve Jobs preferred using our iPhone case.”

Of course, it’s really common online, whether you’re selling games:

Running an eCommerce store:

Or selling a book:

…or any running business really.

The problem comes when your brand becomes associated with a celebrity who later gets themselves into trouble, therefore destroying their brand and damaging the company’s brand in the process. Not sure if I even need to provide this example, but I’m sure Subway isn’t thrilled to be associated with Jared anymore (though his ads were effective back in the day):

I’d imagine it’s hard to predict these things.

Beautiful People in Design

There’s absolutely no question that advertisers have been using beautiful people to sell their products for decades. A few products in specific come to mind, like perfume, clothing, and alcohol.

And of course, it has been pretty empirically supported that using attractive models is effective.

Something to keep in mind, though, is that by itself, the use of attractive people in design won’t usually move the needle. Depends on your audience of course – I’m sure the strategy is more effective in the alcohol industry than in SaaS.

Actually, a study found that the overall perception of the model, including personality, factored into the effectiveness of the ad (you know from studies above, however, that if someone is attractive, people tend to correlate that with a better personality).

Beautiful Design (or Creating a Good First Impression)

It isn’t just beautiful people that can induce a Halo Effect on your site; it’s beautiful images and design, as well.

As Gregory Ciotti wrote on the Unbounce blog, regarding attractive people in design: “Does this mean it’s time to bust out the modelesque photos? Not quite. The main takeaway here for marketers is photo quality is important, creating “attraction” in the sense of polish and professionalism.”

We just published an Academic Insight on why people trust/distrust websites. The most reported factor: a site’s visual design – its use of colors, site layout, layout complexity, and photographs.

Here’s a quote from one of the study participants: “When I visited their site it looked very cheaply put together and the overall appearance of the site and products made me not feel safe shopping there.’’

It’s a trust issue. Make people feel safe on your site, and quickly. (Image Source)

It turns out that first impressions are important online, and design issues affect those first impressions, leading to a possible mistrust of a website.

We know it takes about 50 milliseconds (that’s 0.05 seconds) for users to form an opinion about your website that determines whether they like your site or not, whether they’ll stay or leave.

Sometimes, beautiful websites just make you think they have their shit together.

Listen, though: this isn’t to say beautiful websites always perform best. That’s not true at all. In fact, the Halo Effect goes both ways – you could be limiting your testing program by ruling out variations that aren’t ‘beautiful enough.’ It’s about what works, not what’s prettiest.

That said, the research tells us people tend to associate beauty with quality and all those other nice traits, so it’s good to keep in mind.

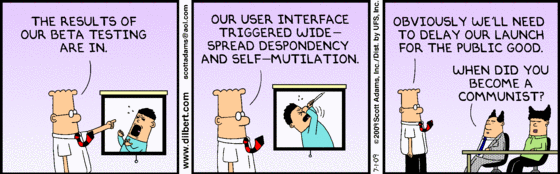

One Broken Piece Can Ruin the Whole Thing

Even if it’s beautiful, it’s gotta work. One poor usability issue can paint the rest of the website and brand as being poor. Jakob Nielsen from NN/g talked about this a few years ago in relation to internal search and complicated setups:

Jakob Nielsen:

Jakob Nielsen:

“An example we often see is that the quality of a website’s internal-search results are used to judge the overall quality of the site, and, by inference, the quality of the brand behind the site and its products.

Thus, a user’s statements may proceed as follows if verbalized in a thinking-aloud study: “Wow, these search results make no sense and appear in seemingly random order. This site must be really poorly done. This company doesn’t have its act together and doesn’t care about customers. I shouldn’t buy any of these products.”

Note that each step in this chain of inferences is at least a little bit reasonable, and yet the final conclusion doesn’t follow from the initial observation. (Sometimes you’ll get a good product when buying from a site with poorly-implemented search.) However, users don’t really progress through a logical reasoning process. The Halo Effect works by shortcutting all these steps and simply allows people to make their overall judgment based on their impression of one attribute.

Similarly, if it’s horribly complicated to set up an account for a service then that bad user experience will rub off on people’s expectations for the rest of the service.”

Optimizers sometimes focus on cosmetic changes, like changing button colors or hero images. But usually, the biggest wins come from simply fixing shit that is broken.

And that’s why usability testing and user research is so important. Find the bottlenecks in your site where users are frustrated, struggling to complete tasks. Fix them. Profit.

Corporate Brand Name

Most people tend to trust a shoe from Nike. Because of the brand name and the strong reputation athletic shoes, people also tend to trust golf balls and golf clubs from Nike.

According to an article in the Houston Chronicle, “Some corporate names become powerful marketing tools in their own right, which can lead to a halo effect to marketing other products.”

This is more an issue of brand equity, so not as much under the domain of website optimization, but it’s still important to know in the context of the Halo Effect.

A Rising Tide…

A similar variation of the brand equity effect is when a product does really well, it makes the rest of a company’s catalog look attractive as well.

Al Ries talks about this version of the Halo Effect in relation to the iPod. In 2005, basically all of their numbers jumped impressively. Apple Computer sales were up 68% over the previous year. Profits were up 384%. And the stock was up 177%. Ries attributes this to the Halo Effect of the iPod:

Al Ries:

Al Ries:

“During the year, Apple bombarded the public with TV advertising, print ads and billboards touting its iPod. Very effectively, too. Apple share of the digital music market is 73.9%. The iPod brand is so dominant that almost nobody knows which brand is in second place. (For the record, it’s iRiver with a minuscule 4.8% share.)

What about the marketing support for Apple’s line of personal computers? The company can’t have spent very much. I can’t remember seeing a Macintosh advertisement during the year, can you?

Which is exactly the point. Apple put the bulk of its marketing budget behind the iPod creating a halo effect that helped the entire Apple product line.”

This works in an industry context, too. For example, Amazon’s Prime Day created a halo effect for other retailers, with online traffic increasing by an average of 21%, and conversions also rising by 57% on average.

One Trait to Lead: Go with your best horse

The Presenter’s Paradox says that simply increasing the quantity of items, or the amount of benefits in copy, doesn’t increase the perception of value. Instead, think about the one value proposition, benefit, or quality that can raise the whole ship.

Al Ries, who, for years has been advising to focus your marketing message on a single word or concept, wrote, “To cut through the clutter in today’s overcommunicated society, place your marketing dollars on your best horse. Then let that product or service serve as a halo effect for the rest of the line.”

Think about a company like Buffer and their focus on transparency, or how Creative Live‘s marketing efforts mostly center around their founder’s affability and expertise. These single aspects touch upon all others in the mind of the consumer.

Avoid The Halo Effect in the Boardroom (and in Your Testing Program)

In addition to using the Halo Effect as a persuasion technique, you should also be aware of how it can affect your optimization strategy.

Left unchecked, it can sway decisions and even stunt a testing program before it begins.

HiPPOs and High Performing Egos: Don’t Rock the Boat

In the Mine That Data podcast, Kevin Hillstrom gave a great example of a catalog executive who has decades of experience, is very successful, has a nice house, and has built his credibility upon his catalog expertise. However, if Hillstrom brought him math and results that showed catalogs not to be effective, he’d likely tune it out.

Why? The post hoc indicators of success (business is doing well, executive very successful, etc.) create the idea that everything about the business is well-tuned. “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it,” right?

This is the Halo Effect in the boardroom. As the Economist defined it, “It is the phenomenon whereby we assume that because people are good at doing A they will be good at doing B, C and D (or the reverse—because they are bad at doing A they will be bad at doing B, C and D).”

The same idea works at a company level.

Once a business does things one way, and it is seemingly successful (the VP of Marketing knows print ads are working well because he’s had 30 years of success and has the nice house and car to show for it), it’s hard to adapt new ways of doing things (especially when those new methods might support these decisions as being “wrong,” making VP and the company look inadequate).

This is a large part of what Phil Rosenzweig talked about his bestseller, The Halo Effect. Basically, we always try to explain the success or failure of a business, and how we explain the success or failure depends on when we analyze it.

While Cisco was exploding in growth, John Chambers was praised as the best CEO in America, their culture was praised (“Nobody has this much fun going to work,” said Wired), their voracious acquisition strategy was praised, they were said to be highly customer-centric, and their product line expansion was praised (described as “deftly maneuvering into new areas,” by Fortune).

When the company began to tumble, all of the things they were once praised for were cited as the reasons for their failure (culture was like the “Wild West,” acquisition strategy was random and too aggressive, company wasn’t customer-centric, etc.)

It seems silly that everyone would have been so fickle with their attributions, but we all do this – it’s a function of the narrative fallacy.

Test Ideas and Their Hidden Halos

Deciding what to test is one of the most important questions in optimization. After a few iterations, you and your team can probably learn to run a test the right way, but deciding on and prioritizing tests is always hard work – especially when egos enter the mix.

Andrew Anderson actually has a really good section on the Halo Effect, specifically in relation to how it affects testing prioritization and decisions, in a previous article on ConversionXL.

Andrew Anderson:

Andrew Anderson:

“We really do trust good looking people and good looking pages more, despite the fact there is no correlation to actual outcomes. We assume that because some expert can speak well that this must mean that their information is better than those that aren’t as eloquent. We really do choose the tallest presidential candidate in almost all elections even though that should have no correlation with their ability to lead.

Example: Every page analysis that has ever taken place. You don’t like the look of the page so everything, especially that CTA, needs to go. In reality, your impression of a page or how much you like any part of the experience has no bearing on the value of that item to performance.

What you should do: Let people vote beforehand for what they think will do best and second best out of all the options you test. Do this even a couple of times, and it will become apparent that no one – be it the most seasoned marketer or the new intern – can tell the performance of anything by just looking at it.

While some people are slightly better than others in choosing an option that is slightly better, very few, if any, will even come close to a 10% success rate in choosing the best option. Confronting this bias head on will also force you to test out things that people consider “ugly” or that go against their vision of the site, and when they win it allows you to really open up what the real best user experience should be.”

This further drives the point that humility is an incredibly important trait for an optimizer. As Craig Sullivan said, “hire the humble one.”

Conclusion

The Halo Effect affects both consumers’ judgment of websites (and products) and our decision making from a strategic standpoint.

On one hand, you can use the Halo Effect to alter the perception of your website, brand or product. Just associate it with something attractive or successful, and the rising tide lifts all ships.

On the other hand, the Halo Effect is dangerous to an organization in a few ways. First, it alters post hoc evaluation of success. Just because you’re doing well, doesn’t mean every part of your company is doing well. Just because an executive is rich and successful and experienced, doesn’t mean he knows which variation you should implement (“In God we trust; all others bring data”.)

Business & Finance Articles on Business 2 Community

(178)

Report Post