By Mark Wilson

The year was 2022—a lifetime ago.

OpenAI, Midjourney, and Stability AI were going viral in an endless stream of posts shared on social media. The world dropped its collective jaw at the ability to type a few words and transform them into realistic photos, product renders, and rich illustrations.

And Adobe, the most famous media-editing company in the world, was oddly, even awkwardly quiet. For nearly a year.

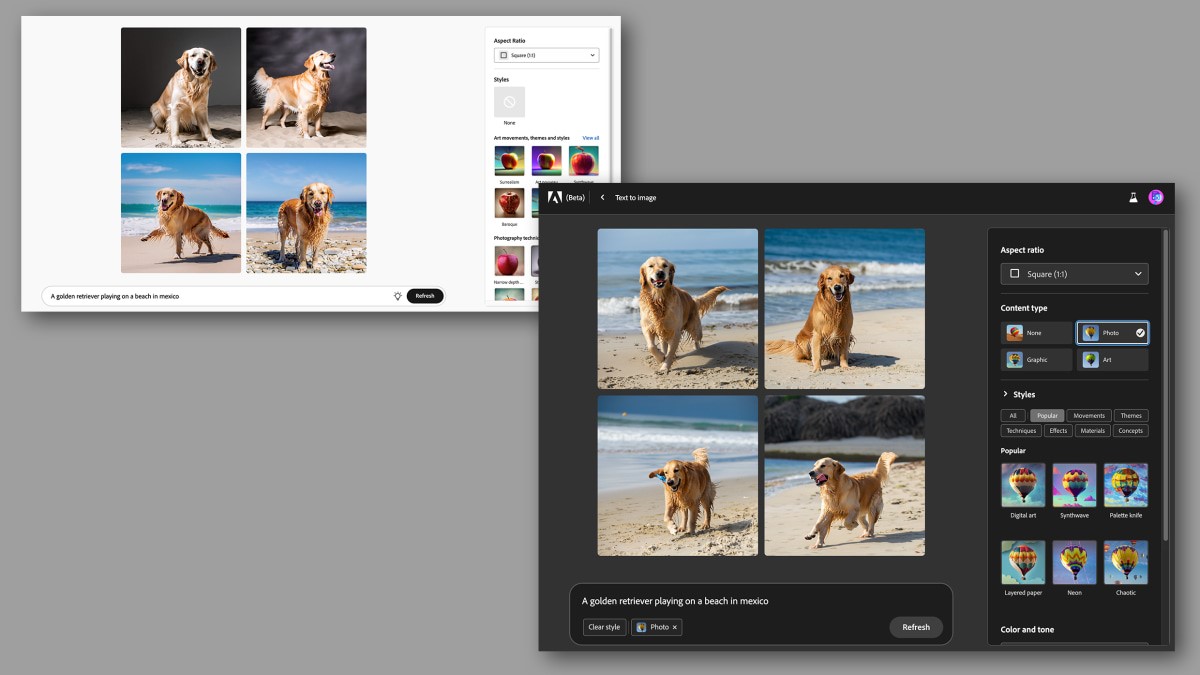

It wasn’t until March of 2023 that Adobe revealed its own take on generative AI—a public beta site called Firefly, which featured a small collection of AI experiments. Firefly allows users to erase an area of a picture and “generative fill” it with a newly imagined image, and create a new typeface dripping with slime, peanut butter, or any other idea you could think of. The public response was measured. Some celebrated the intuitive interface for AI, while others quickly pointed out the limitations and flaws of Adobe’s proprietary AI models. Considering the remarkable speed with which people embraced platforms like ChatGPT (which had 100 million users in its first two months), it was unclear if Firefly was too little, too late. Especially given that, in the same month Adobe’s beta debuted, its competitor, Canva, was already integrating several generative AI tools into its core app.

Yet half a year later, Adobe’s stock price is no worse for the wear, as its revenue has grown 10% year-over-year. In a series of exclusive conversations with Fast Company, Adobe’s technologists and designers shared more insights about what took them so long—and why they believe that their slower launch will pay off in the long run. To Adobe, the future of generative AI is not about automated magic tricks dreamed up by a machine, but about sneaking AI into a creative’s existing workflow and allowing someone to truly realize the picture in their heads, while promising that picture won’t get them sued in the process.

“For us, over time, creative control is going to be a differentiator,” says Eric Snowden, VP of design at Adobe, who spends about 80% of his time on Firefly now. “And I think that’s what our customers want, and why they come to us instead of someone else.”

Adobe’s early AI dominance

“I’ll start my story in a dark room in Santa Cruz,” says Alexandru Costin, with a hint of drama. Costin, Adobe’s VP, Generative AI and Sensei, recounts being late to a presentation at Adobe’s research retreat in 2018, when researcher Cynthia Lu was showing off a concept for GenShop: Generative Photoshop. Using a photo of herself standing on the beach, she was able to swap out her dress with a button press.

“It looked like science fiction to me at the time,” says Costin, who connected after the presentation to ask if this idea was real. “She said, ‘We have a demo.’”

By 2019, Adobe had already been using AI in its tools for many years. Beloved Photoshop tools like Content Aware Fill had been around for nearly a decade, and the company increasingly leveraged AI to power its reality-melting tools. (In 2014, Adobe even made a play to offer some of this core technology as an SDK, in an attempt to position its technology as a backbone of mobile apps while chasing continued relevance in the smartphone era.) But for Costin, the GenShop demo provided a mental breakthrough about how Adobe should approach its software.

“If we actually embraced this vision of using AI as the core of the creative tools, how far can we take it?” he asked. The question wasn’t rhetorical. Around 2020, Costin helped lead the charge to more aggressive experimentation with AI in Adobe’s apps, like neural filters, which used AI to colorize an old photo or even age someone’s face. Neural filters proved to be one of the most successful features in Adobe history. Such features were landmark, Costin says, in that they were using AI to help artists create new pixels that never existed before.

Much of Adobe’s neural filters work was based on the machine learning of GANs—generative adversarial networks—which stacked two AIs against one another. Essentially, one AI would paint an image, attempting to convince the other that it was real, again and again, until the results seemed real to anyone. The curveball came in 2022, with the rise of large language models and diffusion models from companies like OpenAI, which raised the bar of generated content by a solid mile. Adobe, sitting on decades of AI work, had plenty of talent—but no modern AI model to compete with.

Building Firefly

The Adobe team spent 2022 surveying the field and deciding how to respond. One of their early musings was, should it simply license this technology—like Dall-E from OpenAI—and build its apps atop the models of other parties? (After all, that’s how most AI startups are doing things today—even the AI leader, Microsoft, ultimately invested billions in OpenAI instead of trying to beat it.)

“The first question at hand was, ‘How do we get this into our customers hands?’” says Ely Greenfield, CTO at Adobe. “It wasn’t, ‘How do we build it ourselves?’’

But the generative AI models of today were built unapologetically in a technological smash-’n-grab that sucked up writings and imagery from across the internet to build massive datasets of human work from which the AI learns. These models can talk and draw like you because they learned from you—and if you hadn’t noticed, you were in no way compensated for these “tutorials.”

“When we were evaluating the models, one of our big stakes in the ground was this has to be ethical. We can’t be using data from all over the internet,” says Brooke Hopper, principal designer for Emerging Design, AI/ML at Adobe. “I come from eight years of working on drawing and painting apps, and the illustration community was very understandably [like], ‘You’re taking my work!’”

Ostracizing its own users was a major concern for Adobe. Its core community of creatives was the most vocal about the consequences of generative AI taking their jobs—as well as the lack of licensing behind training these models. Furthermore, Adobe’s lawyers wanted to avoid lawsuits of their own. OpenAI and Microsoft are facing multiple class action lawsuits claiming the models have breached consumer privacy, and the New York Times has blocked OpenAI’s web crawler while it reportedly considered suing the company for using its work without licensing. Images generated from unlicensed content could be a legal risk for creatives.

Instead of strip-mining the internet, Adobe decided to train its AI on Adobe Stock—the company’s library of photos and illustrations with a known, paid provenance—and other licensed imagery. This single decision may be the biggest determinant of Adobe’s success in AI generation over the next few years.

On one hand, Adobe seems to have sidestepped legal troubles—for itself and creatives. Creatives in particular won’t accidentally generate an image that contains IP from another brand. (Though Adobe has still fielded accusations from artists that its sometimes targeted generative tools infringe on their copyright, while others claim Adobe used their Adobe Stock submission to train an AI without express consent.) On the other hand, Firefly is worse at generating many things than its competitors in this space.

Take a superhero. Adobe’s AI has never seen a Marvel or DC character. When I asked Firefly to paint a superhero flying through the sky, it gave me results that looked like a random person wearing a T-shirt had put on a cape. Why? Because those are the options in the Adobe Stock library from which it learned. And Adobe AI hasn’t seen Endgame.

“It’s a feature,” says Costin about Firefly’s intentional blindspots around corporate-owned characters. “We’re not worried about short-term quality flaws.” Down the line, he suggests that Adobe could always partner with companies, either licensing their IP to expand Firefly’s purview, or even building a custom model for a company like Disney to use its own characters for generative AI. In fact, currently, Adobe offers companies an enterprise version to train their own Firefly models.

Designing an AI

By 2023, Adobe had a plan in place. Costin stepped into his role on January 12 of this year to begin development on Firefly, and in a highly accelerated development schedule, Adobe shipped the first iteration of Firefly by March 21.

To do so, Costin says that Adobe shifted “from design thinking, or a design-first methodology, to a research-first methodology.” Basically, that means Adobe’s research team led development by creating its generative AI model. Countless iterations of this model were handed over to the design team, which before they began working on the front end design, put particular efforts into testing the model’s functionality.

“I’d say that’s most of our time, focusing on, ‘Is this model doing what our customers expect and at a quality Adobe can be proud of?’” says Snowden. “That takes up a lot more time than the UX design and things you’d traditionally think of us doing as a design group.”

Engineering and design went back and forth rapidly during the development stage, testing a handful of models at a time on a simple website, with updates coming in 24-hour periods. Much of the feedback from the design team was creative in nature: What should the line width be on an Adobe-style Firefly illustration? And designer feedback did a lot to shape the aesthetic of Firefly’s results, including the company’s preset styling options.

Another particular concern was, if Firefly-generated images demonstrated algorithmic bias (which even OpenAI founder Sam Altman concedes is a rampant problem in his industry)—like, were all doctors white men because that’s what the system had been trained to see in examples? “That’s not exactly a model [problem], really; that model is capable of creating any human being. And that’s not exactly a UX [problem],” says Snowden. “But it’s a principle to make sure people are seeing themselves in this product.”

So Adobe opened a Slack channel for its global workforce to try out the AI, and test for issues like bias, refining the model to eliminate the most egregious errors. While this sort of work is ongoing, Adobe did develop a system to help results feel more representative without actually eliminating bias in the model itself. Any time you generate a person in Firefly, Firefly takes into account your location, and it cross references the demographics in your area to generate an image of a doctor, teacher, or any other person most likely to be familiar to you. (The catch, of course, is that such a solution doesn’t really challenge stereotypes in regions where most doctors are white.)

As Adobe refined its model, the design team implemented the front end of Firefly extremely quickly. That’s because it built the system to work with Adobe’s existing Spectrum design language and UI logic, arranging the canvas and tools in patterns that would be familiar to any Adobe product user. (In fact, every time you query Firefly, it’s actually referencing a dozen or so different Adobe historical AI models outside of Firefly—which is another reason the tools feel so familiar.)

“It’s like little pieces of a house coming together,” says Hopper. And this is the regard where Firefly really shines. While I often find Firefly’s generative models fall short of my inner vision, the act of turning avocado toast into a typeface couldn’t be simpler thanks to its refined UI.

Where Firefly goes next

For now, Firefly is mostly a stand-alone demo site (and you can try it in betas for Photoshop, Illustrator, and Express), but its tools will increasingly work their way across the Adobe Creative Cloud in a more official capacity. Meanwhile, Adobe confirms that more advanced capabilities, such as generating full video and 3D objects, are on the horizon.

But for Adobe, the ultimate question comes down to not just how well Firefly generates convincing images, but how close it can get a user to the core vision trapped in their head. That requires doing more than typing the perfect prompt. And this is where Adobe’s team believes its advantage remains long-term—why it believes you’ll continue to use its products to create and tweak imagery, even in an era when machines can imagine our dreams by typing.

“Some people say you’ll tell the computer what to do, and it’ll do it all for you. It’s not going to be that,” says Greenfield. “It’s going to be multimodal, heavily iterative . . . and involve styluses and mice and selection areas and timelines and many of the same metaphors we use today.”

In other words, Adobe believes the future of generative AI is about what Snowden called “creative control.” It’s more than the prompt. It’s the buttons and knobs, the selectors and erasers that Adobe believes will still remain key to editing media in the future—even when AI paints the first pixels. It’s an argument than serves Adobe’s extensive platforms well, but it’s also the most realistic solution for creative professionals. The question remains, however: Will Adobe be so bold as to break its own molds and offer up a unique piece of software within generative AI that creates the sort of magic we can’t imagine just yet?

“When Adobe makes new products, we’re successful when we’re tied to a shift in user need,” says Snowden, who cites that the countless photos taken by digital cameras necessitated Adobe’s Lightroom even when Photoshop already existed. “Will there be a shift with that in generative AI? Maybe. I don’t think we have the answer to that yet. But we know the power of our existing tools and generative AI together—there’s kind of nothing else like it out there.”

(13)

Report Post