Spending the budget on the other guy

At the time of writing, the US election is approaching its final few days of what seems like an eternal trail of speeches and mud-slinging. It’s a presidential campaign that has been defined by its digital content. With the traditional rallies largely cancelled for social distancing reasons, much of the debate has been conducted online. Advertising and messaging has been crucial.

For politicians, it’s often easier—and safer—to attack what your opponent says rather than document your own policies. It’s a tactic perfectly suited to Trump’s outspoken personality.

According to the New York Times, roughly 80% of the Trump campaign’s ads have been either negative or what’s called a contrast ad, a mix of criticism of the opponent and self-promotion. Of those, 62% were all-out attacks.

For the Biden campaign, about 60% of ads have been negative or contrast, with just 7% outright negative.

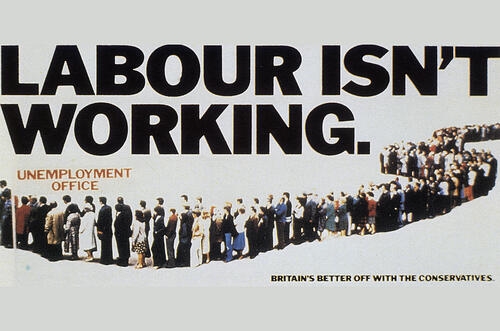

Calling out the competition isn’t limited to US politicians, and it’s hardly a new approach (even if it has been pushed to extremes in recent years). Saatchi & Saatchi’s infamous “Labour isn’t working” campaign is credited with swinging voters to Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative Party back in 1978.

Thatcher was initially concerned about directly mentioning her political opponents, the Callaghan-led Labour Party.

But the poster struck a nerve. The Chancellor of the Exchequer, Labour’s Dennis Healey, attacked it as “soap powder advertising” in the House of Commons, which of course only resulted in greater publicity. It became headline news. And Thatcher became Prime Minister.

He who shall not be named

The discussion about competitors is also relevant for business organizations. How do you go about referencing a rival’s products or services without giving them free publicity? What if your prospects may not have even heard of your rival, but you inadvertently point would-be customers directly towards a competitor?

The running joke at some of the global brands we’ve worked for is that the direct competition is known as Voldermort—he who must not be named. Even uttering the competitor name internally was frowned upon.

But why? Let’s analyze this for a minute and unpack some of the arguments.

Firstly, will your prospects honestly have never heard of your competitors?

Customers almost always undertake due diligence. Whether it’s a consumer buying a new washing machine or an enterprise looking to implement an ERP, a shopping list of features and prices will be compiled. Procurement will be asked to compare multiple quotes from vendors. If your competitor is a genuine rival, it’s unlikely that customers will not come across them as part of their own research.

So if prospects are likely to be aware of competitors, why the reluctance to talk about them?

A grown-up approach

It can be argued that acknowledging the fact that competitors exist shows a level of maturity. Pretending someone or something isn’t there can seem childish. Refusing to recognize its existence won’t make it go away.

Talking about your competitors demonstrates a degree of self-confidence. “Yes, we’re happy to talk about another organization, because we’re comfortable with who we are, and can explain how we’re different. It’s immature to pretend they don’t exist, so let’s draw up a comparison and explain why we’re different.”

Note that this doesn’t give you free rein to constantly criticize a competitor. Belittling another can easily come across as needy and tawdry. Chances are your audience will think less of you than the organization you’re trying to attack. Instead, an argument needs to be balanced, detailing strengths as well as perceived weaknesses.

It’s something we advocate here at TP. Creating battlecards can be a hugely important deciding factor in helping prospects to convert. At the right time in the sales funnel, when the prospect is close to making a purchase and is making final considerations, clearly outlining how your offering differs from another can close the deal.

It’s all about deciding when the moment is right to talk about the elephant in the room. And then how you execute the plan.

Please don’t buy from us

As a main sponsor of the London 2012 Olympic Games, British Airways had a great opportunity to cash in on the Games’ global appeal. Its advertising strategy was a courageous one: “Don’t fly. Support Team GB.”

The thinking was that home advantage only counts if you’re at home. So a business that makes money from people traveling told its customers not to travel for the benefit of GB’s medal chances.

Its B2B angle was equally difficult. How do you tell the travel industry sector that you’re currently spending a huge amount of money to tell consumers not to book flights with them, potentially risking their livelihoods?

The answer is that it was a calculated risk. Although the messaging seemed counterproductive, the hope was that customers would admire the stance, keep the airline top of mind, and come back in droves after the Games. BA was seemingly sacrificing its performance for GB’s athletes’ performances. Its ‘cool’ factor would outweigh any possible negatives.

It’s worth noting that BA was awarded Superbrand of the year four years in a row following the London 2012 Olympic Games. I guess you could call that a successful gamble.

Good publicity? We’re lovin’ it

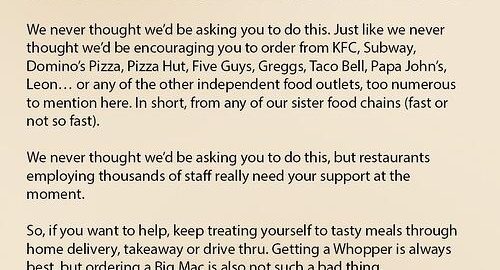

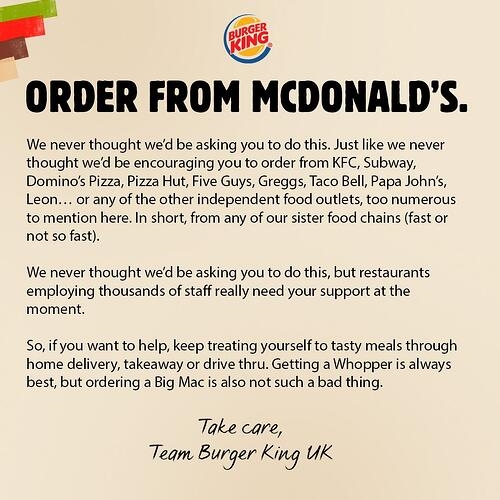

In an equally controversial move, Burger King recently released a statement telling customers to “Order from McDonalds”. This takes BA’s strategy one step further: not only don’t buy from us, but buy from our biggest rival instead.

Once you read the full statement, you can see the context. With lockdowns having a huge impact on the hospitality sector, Burger King is showing solidarity with its fellow operators. It’s simultaneously looking at the big picture, while also analyzing the personal impact on individuals who work in competitors’ restaurants.

It’s not just McDonald’s who gets called out either. In total there are 17 outlets named in the statement. It’s clever; while the headlines will concentrate on McDonalds, the statement isn’t focusing solely on them. It’s a call to arms for the fast food sector as a whole, ultimately saying that what’s truly important is that the employees of McDonald’s, KFC, and all the other restaurants hold on to their jobs. Rivalries are put aside so that people can provide an income for their families.

There are no risks to naming McDonald’s. Everyone knows who they are. So it’s great publicity for Burger King, as they get kudos and everyone comments on how classy they are.

It’s a smart move, at the right time, and beautifully executed.

Part of a community

While Burger King is a key player in their community, others are looking to join the big league in their own industry.

For startups and disruptors, publicly calling out the competition may indicate the market they want to be a part of, rather than the one they are currently in. It’s an aspirational play, similar to upcoming boxers who see themselves as future title contenders, calling out the current champions in a bid to become the next big thing.

It’s rarely that simple, or that quick. Hitting the big league can often involve time and patience, not to mention a lot of hard work. But maybe calling out the established players can get your organization noticed and your name added to that procurement shortlist of possible vendors. If you make the right noise, and get your powerful content seen by the right people, you can start to make inroads.

After that, once you’re finally in the ring and ready to stand toe-to-toe with your competitor, it’s all down to your product and service offering.

Go get ‘em.

Business & Finance Articles on Business 2 Community

(21)