By Ahmed Elgammal—The Conversation

Making art using artificial intelligence isn’t new. It’s as old as AI itself.

What’s new is that a wave of tools now let most people generate images by entering a text prompt. All you need to do is write “a landscape in the style of van Gogh” into a text box, and the AI can create a beautiful image as instructed.

The power of this technology lies in its capacity to use human language to control art generation. But do these systems accurately translate an artist’s vision? Can bringing language into art-making truly lead to artistic breakthroughs?

Engineering outputs

I’ve worked with generative AI as an artist and computer scientist for years, and I would argue that this new type of tool constrains the creative process.

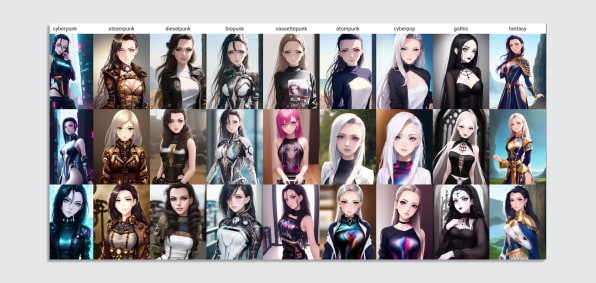

When you write a text prompt to generate an image with AI, there are infinite possibilities. If you’re a casual user, you might be happy with what AI generates for you. And startups and investors have poured billions into this technology, seeing it as an easy way to generate graphics for articles, video game characters and advertisements.

In contrast, an artist might need to write an essay-like prompt to generate a high-quality image that reflects their vision—with the right composition, the right lighting and the correct shading. That long prompt is not necessarily descriptive of the image but typically uses lots of keywords to invoke the system of what’s in the artist’s mind. There’s a relatively new term for this: prompt engineering.

Basically, the role of an artist using these tools is reduced to reverse-engineering the system to find the right keywords to compel the system to generate the desired output. It takes a lot of effort, and much trial and error, to find the right words.

AI isn’t as intelligent as it seems

To learn how to better control the outputs, it’s important to recognize that most of these systems are trained on images and captions from the internet.

Think about what a typical image caption tells about an image. Captions are typically written to complement the visual experience in web browsing.

For example, the caption might describe the name of the photographer and the copyright holder. On some websites, like Flickr, a caption typically describes the type of camera and the lens used. On other sites, the caption describes the graphic engine and hardware used to render an image.

So to write a useful text prompt, users need to insert many non-descriptive keywords for the AI system to create a corresponding image.

Today’s AI systems are not as intelligent as they seem; they are essentially smart retrieval systems that have a huge memory and work by association.

Artists frustrated by a lack of control

Is this really the sort of tool that can help artists create great work?

At Playform AI, a generative AI art platform that I founded, we conducted a survey to better understand artists’ experiences with generative AI. We collected responses from over 500 digital artists, traditional painters, photographers, illustrators and graphic designers who had used platforms such as DALL-E, Stable Diffusion and Midjourney, among others.

Only 46% of the respondents found such tools to be “very useful,” while 32% found them somewhat useful but couldn’t integrate them to their workflow. The rest of the users—22%—didn’t find them useful at all.

The main limitation artists and designers highlighted was a lack of control. On a scale 0 to 10, with 10 being most control, respondents described their ability to control the outcome to be between 4 and 5. Half the respondents found the outputs interesting, but not of a high enough quality to be used in their practice.

When it came to beliefs about whether generative AI would influence their practice, 90% of the artists surveyed thought that it would; 46% believed that the effect would be a positive one, with 7% predicting that it would have a negative effect. And 37% thought their practice would be affected but weren’t sure in what way.

The best visual art transcends language

Are these limitations fundamental, or will they just go away as the technology improves?

Of course, newer versions of generative AI will give users more control over outputs, along with higher resolutions and better image quality.

But to me, the main limitation, as far as art is concerned, is foundational: it’s the process of using language as the main driver in generating the image.

Visual artists, by definition, are visual thinkers. When they imagine their work, they usually draw from visual references, not words—a memory, a collection of photographs or other art they’ve encountered.

When language is in the driver’s seat of image generation, I see an extra barrier between the artist and the digital canvas. Pixels will be rendered only through the lens of language. Artists lose the freedom of manipulating pixels outside the boundaries of semantics.

There’s another fundamental limitation in text-to-image technology.

If two artists enter the exact same prompt, it’s very unlikely that the system will generate the same image. That’s not due to anything the artist did; the different outcomes are simply due the AI’s starting from different random initial images.

In other words, the artist’s output is boiled down to chance.

Nearly two-thirds of the artists we surveyed had concerns that their AI generations might be similar to other artists’ works and that the technology does not reflect their identity—or even replaces it altogether.

The issue of artist identity is crucial when it comes to making and recognizing art. In the 19th century, when photography started to become popular, there was a debate about whether photography was a form of art. It came down to a court case in France in 1861 to decide whether photography could be copyrighted as an art form. The decision hinged on whether an artist’s unique identity could be expressed through photographs.

Those same questions emerge when considering AI systems that are taught with the internet’s existing images.

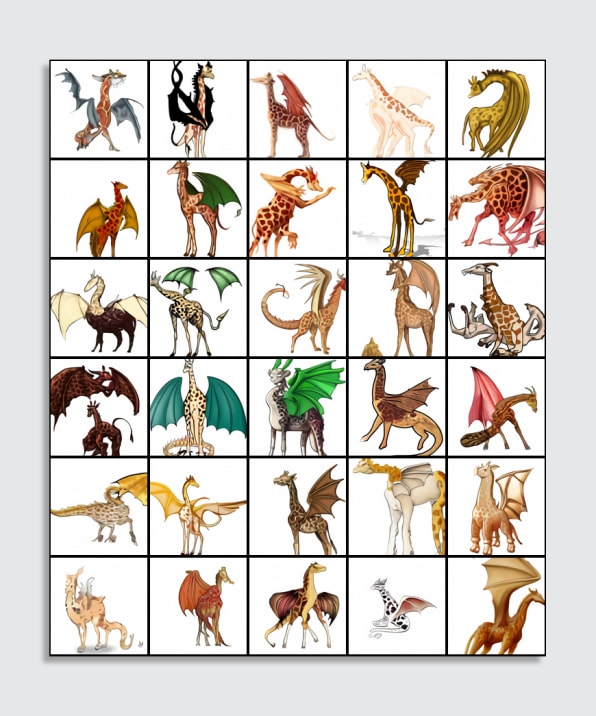

Before the emergence of text-to-image prompting, creating art with AI was a more elaborate process: Artists usually trained their own AI models based on their own images. That allowed them to use their own work as visual references and retain more control over the outputs, which better reflected their unique style.

Text-to-image tools might be useful for certain creators and casual everyday users who want to create graphics for a work presentation or a social media post.

But when it comes to art, I can’t see how text-to-image software can adequately reflect the artist’s true intentions or capture the beauty and emotional resonance or works that grip viewers and makes them see the world anew.

Ahmed Elgammal is a professor of computer science and director of the Art & AI Lab at Rutgers University.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

(32)