Marc Newson dishes on 40 years of jet packs, space Nikes, and why even timeless designs die

On the release of his new book with Taschen, the legendary industrial designer sat down with ‘Fast Company’ for a discussion as wide ranging as his career.

BY Mark Wilson

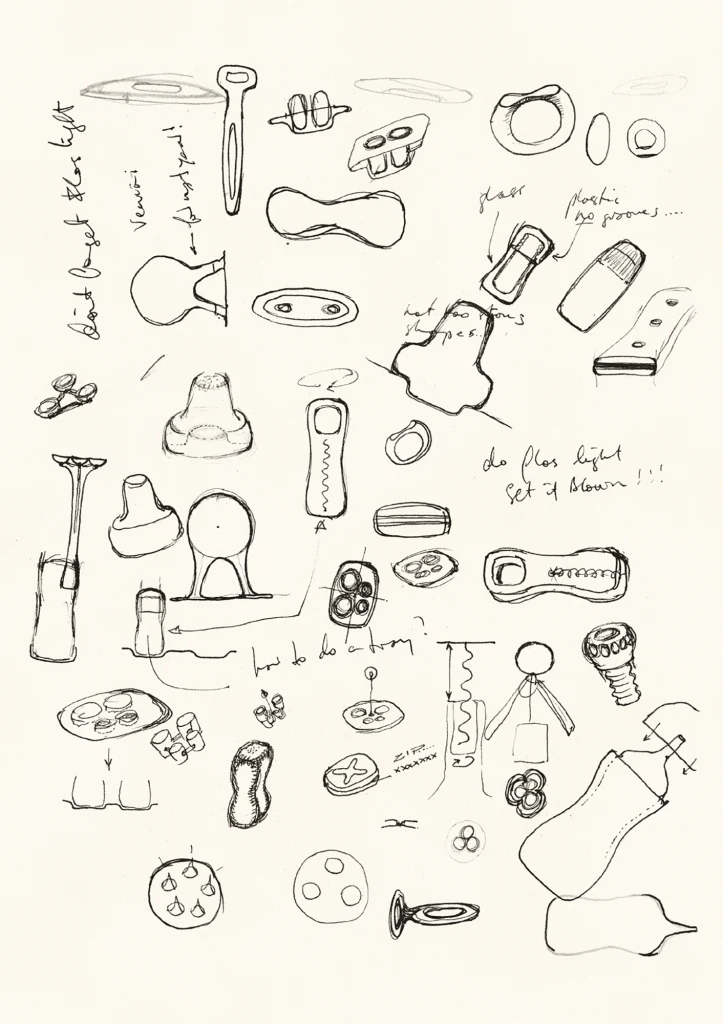

No doubt, a retrospective makes you introspective, and Marc Newson is in a career-analyzing mood when we meet for lunch at the Mandarin Oriental hotel during Milan Design Week. Between plates of spring rolls sits the industrial designer’s latest project: not a luxurious watch or boat, not a $3.7 million chair made from the riveted aluminum of an airplane nor a sex toy made from silicone and molded as an abstract breast.

It’s a true, blue tome of a book: Marc Newson. Works 84-24 ($200), which breaks down Newson’s 40-year career, from 1984 to today, through the things he’s created. Over that period of time, the LoveFrom cofounder has designed almost every object you can think of (silverware, seating, even a Tokyo public restroom), but the new book takes you through his staggering list of creations in a straightforward manner. Works are assembled chronologically and in sections for Objects, Furniture, Interiors, and Transport. Each project features a significant amount of written detail, process imagery, and detailed photography.

“Books now are sort of like jet packs. Slightly anachronistic,” he says, with a dry chuckle at one of his own designs. “Though books are actually a thriving business, and it gives one an opportunity to catalog everything properly.”

Over the course of an hour-long conversation (lightly edited below), he revealed not only his philosophies on design, but his views on his own creations, the entire industry of making stuff, and where design might be going next in a moment when even “timeless design” has proven to be a transient concept.

Why did you make another book? Why now?

Basically, the last book I did was 12 years ago, but it was a sort of book that Taschen refers to as an “art edition.” It’s meant to be sort of expensive. We had the intention of producing a more mainstream, accessible type of a book for a student. We just never got around to doing that because there was always another project. There was never any kind of urgency.

But then it kind of got to the point where I was like, you know, we really have to do this. And there was 10 years more work to put into it. So it’s far more succinct [than the previous edition]. It only includes projects, which are actually, physically out there, while the last book included a whole bunch of stuff which was unrealized. So, this was the book that was supposed to be, in effect.

It’s a very digestible reference to your work, which is just hard to duplicate online through any website or social feed.

Totally. I think it is very important for designers, in particular, to actually be able to search through things—to sit down and absorb a focused retrospective on a topic, rather than just the mix of their Instagram feed. I feel like social media is driving so much information overload, where you can’t really edit out an aesthetic.

These sorts of books are almost relaxing; in a way they’re quiet, and you know, you can lose yourself without being sort of distracted. Or, they enable you not to be distracted.

I’d love to talk about your approach to shape—flipping through so many projects back-to-back, you can really see how you play with this distorted, rounded rectangle in countless ways across your designs, whether it’s a car’s front end or a chair’s bottom. It’s something you’ve spoken to before, but unpack this shape for me, and why it’s such an obsession.

My response would be pragmatic in the sense that it’s somewhere between a square and a circle. You’ve got the two, I might call, most fundamental two-dimensional shapes. That’s the black and the white. And then there’s just like a myriad of grays in between.

[The grays] are where you sort of inhabit—more so toward the circle side of the spectrum, rather than the square. I’ve never really been one for really hard-edge things. A long time ago, my work was referred to as sort of organic or retro-future lead. There’s all these sort of weird definitions.

Your work has never felt organic to me—even the Lockheed Lounge I’d never call “organic.”

I mean, they’re sort of meaningless descriptions, really. I’ve always felt that my work was far more sort of restrained than that. There was an order. There’s a reason. There’s a kind of a logic and pragmatism. But form itself, in a formal sense, is really, really complicated.

Shapes for me are often vehicles to carry an idea; but in some ways that they’re arbitrary as well. Form is a canvas. It’s a communicator. A kind of a concept to demonstrate a certain kind of technology, or a certain process.

I’d say a unifying part of your design is you’ve never been simply drawn to a base function. You’re always more expressive.

It depends what the thing is, you know, if it’s a pair of binoculars . . .

Take the Sukeban Japanese female pro-wrestling league championship belt you just made! That would be quite a juxtaposition to the shape conversation we’re having here.

That’s a sort of a strange, outlying project, but nonetheless kind of fun. Fun has always been an important part of what I do. You know, a sense of humor or lightness. I’ve always felt uncomfortable about taking what I do so seriously—although, you know, it’s a really serious job when you’re designing things for airplanes and boats! I’ve done a ton of work in the aviation industry over the years. I spent 15 years working really intensively in that space. And it’s kind of like being in the Army.

You’d even designed a jet pack with BodyJet SAS.

It’s weird. Now it feels like one of those sort of weird, futuristic, utopian kinds of things that seems anachronistic in the world. Like, it’s somehow no longer relevant. I just don’t feel like anyone has an interest anymore.

It’s true. Since that design was released in 2010, it’s now like, “Why would I want a jet pack? We have drones!” I flew a jet pack, briefly, in 2008. But personal flight doesn’t feel like the same dream today.

Right. Drones—[it seems] the concept of some unmanned vehicles are far more acceptable. And appealing, I suppose, in a way. You know, that distance that we create now, between us and reality, is the distance [between us and the drone]. But the jet pack is such a bizarrely analog thing as well.

Which is why I feel like a jet pack could never really work. The core mechanics just aren’t feasible.

Just put on the VR headset.

I was just looking at your TV Chair and Table for Moroso, and at first my reaction was, those are from the 1960s! But, of course, you released them in the ‘90s. Your work can be hard to place chronologically, even in comparison to itself. How have you seen your work evolving over time?

It’s very hard to look at [my evolution] and go, I started there, and I’ve ended there. There’s a discernible sort of language that’s been expressed, amplified, throughout the decades. And [yet], of course, there’s an element where I can’t see the wood for the trees because I’m just, like, immersed in what I do. But at the same time, I do feel one of the greatest compliments anyone could pay me is to say, “your work is recognizable.”

Though ideally it would never always be apparent, either. Because at the same time, I certainly don’t want to sort of slavishly impose stylistic rules. I’m solving this problem for, say, a pen or a pair of binoculars or something super functional. And say it has to contain X number of stylistic hits in my top 10. Although, having said that, I feel like I could sort of write a rule book for myself. I kind of have, actually. That’s why, in a way, I wouldn’t say design has become easier [for me], but it has certainly become faster. What once took me weeks to do takes me days or even hours.

Why is that? Just your mindset? Your tools?

I’ve narrowed down the possibilities within my own context of how I solve problems. There are things that you ask, Should I do this? Or should I do this? Well, 20 years ago, it’d be, like, a choice. Now it’s just, that’s my way.

If I was an author, it would be like using certain vocabularies. It helps. It’s also one of the ways that I can justify or reconcile working on such a broad range of different things. I didn’t really think too much about the difference between designing a mega yacht or something really small. So what helps me to navigate those extremes is knowing that there will be certain commonalities that I can rely on or anchor to what I’ve developed. And they’ve become part of my parameters that I’ve set for myself.

It’s like mental physics.

Yeah, absolutely. It’s almost like sort of deducing a kind of a formula, and you get a little bit closer every time.

I feel like that as a writer, though you can get quite literal with the formula, and that’s when you get a little scared.

Yeah, yeah! True. But nevertheless, it can be helpful. I’ve always thought that my job, and to an extent, the job of any designer, is problem-solving, really. You know, most of the things that we work on exist in one way or another. In many ways, yes, they’ve all been designed already. And actually, in many cases, they don’t need to exist. The choice doesn’t need to be any greater.

So why design?

There’s finding a point of difference—how could I add something? It’s not making it better. It’s how could I express it my way? It’s making it better for me, actually.

No one wants to work in a gratuitous way, especially now. I think restraint is an important topic that obviously comes up more and more and more—justifiably. [However, I wonder] not only is something sustainable practically, but, is it sustainable philosophically?

That was also the great thing about doing a book because it gives me the rare, and maybe one-time opportunity to sort of step back and look at everything holistically. And sort of take stock, actually, I guess in a way to decide if I want to keep being a designer. [laughs]

What did you decide? I guess you have to read to the end of the book.

I guess the point is . . . it’s my job. It’s my career. It’s my vocation. But if I wasn’t doing that, I’d be kind of doing it in another way. I’d do some tinkering in the garage making shit, basically. Maybe not for other people. But inevitably, I guess it would end up being for other people as well. You know, I would just end up building stuff.

And eventually, you end up with enough that you have to either give it away or sell it or something.

Yeah! You know, I’m not a collector; I don’t do this to own it. I kind of do love the idea, on one hand, of being able to populate my world with things that I built and fill a need I feel needs addressing. But at the same time, once it’s done, it’s done.

Do you live with your work?

Some of it, but not that much. It’s hard to say, actually. I guess, increasingly more and more as I get older! I’ve always really prided myself on being able to, you know, ironically, live out of a suitcase. I’ve always loved traveling, so it’s been important [in my work].

Definitely, you’ve so many designed vehicles, luggage, and objects around travel.

And looking at how different cultures solve problems, because we all solve problems in really fundamentally different ways. The Japanese will solve it in a really different way than the French or the English. The French will do it in a really, completely bizarrely, uniquely French way. Go to some engineers in the U.S. and they’d laugh about it. Yet somehow, that’s justified. That’s a fair approach in France. One of the great things about the job that I do is that it is now essentially borderless. There’s no geographical boundaries [to design]. And it’s hard to think about the creative expressions that are not bound by some sort of geographical or regional line.

I mean, that’s dangerous in some ways. Look at cities getting the same architecture, or unique color, being wiped out of many urban spaces as they adopt a uniform gray.

That’s the bad side—a homogenization of everything just because we are now completely international. We are borderless, and it doesn’t really matter where you are in the world, you know, you can work remotely. Whereas when I was growing up, and sort of planning my trade in the early days, it was so [global], and I miss that. I miss the necessity of having to move and to be there. There’s a kind of mental tactility that is associated with that. And I think it’s healthy.

You know, I’m from Australia. But I’ve been based in the U.K. for 30 years, and somehow it’s still a topic. If anyone ever writes anything about me, that fact is generally mentioned within the first two lines.

At this point in life, you don’t feel like an Australian?

No, at this point in life I feel completely international. But I’m trying to think, what is that? What does it mean to be from somewhere? I struggle with it.

You don’t think it’s affected you as a designer?

It’s hard to articulate, but it’s there somehow. Maybe it’s, you know, it was the light growing up or something, you know, wide open spaces or something like that.

What’s it like talking so much about your past work all of a sudden?

People always ask me, what’s your favorite thing you’ve designed? If I get that question one more time. . . . I should just pick something.

You could change it every time. It becomes a running gag.

I’ll do that. It’s a brilliant idea.

You have to commit though, this isn’t a two-week thing. It’s a 20-year thing.

I should have started that 20 years ago.

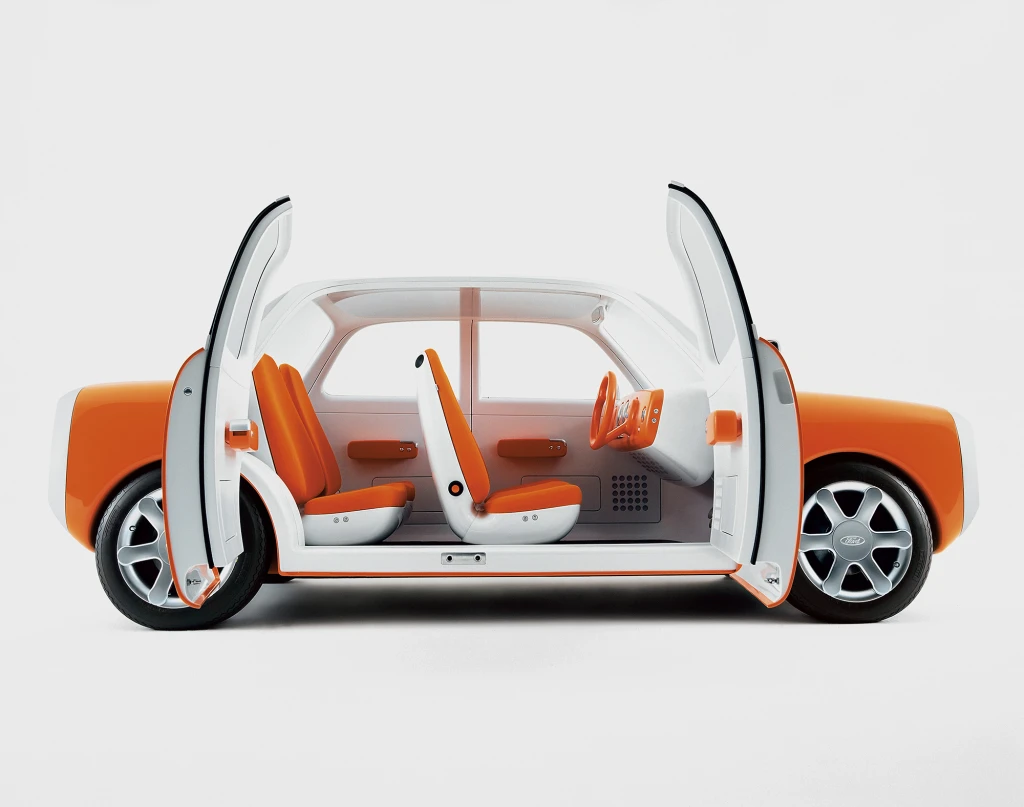

So I was at Nike recently in a meeting with the design team, and your Ford 021C Concept Car came up on one of their mood boards. How does something like that feel?

Nike claims, to this day, well Mark Parker does, that the Nike Zvezdochka was one of the most influential projects that they ever did in terms of influencing the way they produce shoes. Because this was done kind of a long time ago, pre-Crocs.

We kind of reversed the way that [shoes were built], so the structure was on the outside. The whole idea was to mold it [instead of sewing the upper]. You know, there’s so much wastage in that industry. And this was an attempt to sort of address a lot of those [modern] questions that were present a long time ago.

The concept was a convertible project that can be kind of multifunctional. It was actually originally designed for Russians cosmonauts to go into space and be worn at the International Space Station.

How’d the shoe come about?

I became friendly with a guy called Sergei Krikalev, who was the cosmonaut who had spent the most time in space. Years. Listening to him and talking to him about it, it’s a completely mundane experience. It’s really basically doing nothing. You have to kind of occupy yourself, you have to keep fit. Because if you don’t exercise in space, you atrophy. And I thought, keeping fit? Could Nike have a greater calling than that? If there’s one place you need really good trainers, it seems to me, it’s in space.

Yet most of the time, you’re just floating around the cabin with socks on. Krikalev showed me pictures where he’s wearing socks with holes in them and stuff. It’s just hysterical!

Well, they’re only rocketing up so many socks! That’s a million dollar sock in space.

So [I created] a shoe where you can have versions. [The modular design featured a sock to be worn all the time, with a Croc-like exoskeleton and an optional tread in the bottom.]

It was going to space. It was all ready. I had sanctioned it with the Russian Space Agency, and then, at the last minute, it was canceled because it was a Nike-branded product. The government wouldn’t send branded products.

The government would have been endorsing Nike and thereby, America.

It has the name, Zvezdochka, which was actually the name of one of the dogs that went up into space and didn’t come back.

It’s amazing how modern it looks.

They did reissue it in 2014, actually. And I did another project with Nike [the NikeLab Air Vapormax], which is in the book somewhere. It was supposed to be the beginning of a series of three things, culminating in a project for the Paris Olympics. And sadly, it was linked to a handful of guys who got let go.

It almost looks like a Birkenstock on top but a Nike on the bottom.

They were basically moccasins. They were so comfortable that I practically had to have them surgically removed. I don’t have any now because I wore them all constantly.

Honestly, I would not have liked these in 2017 when they were released. But they’d be in style today.

I think maybe they’re more relevant now. At the time, they were kind of . . . no one could quite [wrap their head around them]. Then Travis Scott, like two years ago, wore them at one of his concerts, and everybody was suddenly trying to buy them on StockX. And you can’t get them!

I mean that’s a problem, even for the shoe companies. They have to actually buy back their old archive products. Do you?

We buy stuff on the secondary market all the time. Through necessity. Yes, it’s so weird, isn’t it, with companies like Nike? I mean, like all the companies that I work with, when I try and kind of fathom how—it’d be so easy just to [make more]. There’s such a demand. It’s obviously typical of the industry. When something’s done, it’s gonna die. And there’s always an element of appeal to suddenly have something become rare.

[But] you know, the assumption that something’s going to get made and remain in production is kind of a myth. It just doesn’t happen. Things get made, and then they stop getting made. It’s a kind of moment in time. These companies—whether it’s Louis Vuitton or Nike—all they think about is the moment, the beginning, you know, the drop. But they never ever think about the ends, the trajectory, of that thing.

Now they do but only through the lens of sustainability.

It just sort of fizzles! And that’s, like, okay. No one ever thought about [more]. There was never a plan.

The plan was to do it. And so you tick that box. Whereas designers like me, we’re also sort of thinking about the future. I think every designer desires to create a timeless object—to create things that can stand the test of time and are relevant into the future. The only hitch is that the people making it don’t necessarily see it like that! They’re like, that’s a nice idea, but that’s way too much thinking.

Do you consider any of your designs timeless, or more timeless than others?

Yeah, I’d like to think that all of my things in some ways are timeless. Not in a sort of a pretentious way, but just that they could be as relevant now.

There’s nothing cringe about your designs, like there is when your favorite cut of jeans goes out of style.

Yes, exactly. The best example would be fashion. Fashion is very linked to modes and times. And maybe that will recycle, but design is a bit more like architecture, I guess. But actually even architecture is a bit like fashion, if you think about movements in architecture, like postmodernism or stuff.

Ha! Well, architecture is so material based, and in bringing up architecture, you expand the scale of building objects to 10,000 years. Whereas industrial design is about a century old.

Yeah, it’s so new.

I don’t want to get too galaxy brain right now, but I’m thinking through this, and we transitioned from handmade objects to mass-produced goods. And the consequences of that just have barely been explored in the scale of actual human history.

One of the great things about doing a book is I can go back, actually 40 years, in some cases, which starts to become a meaningful amount of time in terms of understanding how things continue to be or not to be relevant. But it’s only now that I think we can have a reasonable-enough perspective to kind of start to consider those things. Because, you know, it’s a new industry; it’s a new business. And it’s a curious moment because we’re looking at how younger designers solve problems, and looking at the way that they work and, and it’s very different!

Gemini Salt and Pepper Grinders Wood, paint, mechanism

© Marc Newson [Photo: Taschen]

I’ve been thinking a lot lately about how, following the impact of Virgil Abloh, it’s hard to even know what good design is. Once you blow up and remix all references, what’s the anchor? It’s difficult for me to get my grounding now.

It really is. Now, we have the death of craft, simultaneously with that [explosive] trajectory that we’re talking about with design that almost [designs] inversely. And the craft based way of doing things is done. It’s not coming back.

I was lucky enough that I was still able to draw from that, that [craft] history and that kind of reality in a kind of profound way. But it’s not available anymore.

You see that in the sculpt of your work. So much of your work literally starts with sculpture as much as what we might label design.

I trained as a silversmith, basically. I didn’t study design. And so, the idea of being self-taught is a generalization. I think that [craft reference] is certainly something that can exist and should exist, and maybe it’s more relevant now than it ever has been. But, you know, the possibilities are so nebulous now. Like, it’s just kind of mind-bogglingly unfathomable! Everything’s possible, and not necessarily in the good way.

I need five years distance from some work to know if it’s good. And everything is coming so fast now! Will this design acceleration just make us completely untethered?

Absolutely. And more so, will those questions we ask even be relevant? Or are they just kind of analog?

But in any case, this has always been about the future for me. I love the idea of looking into a kind of a crystal ball and thinking, How will this be perceived? I used to always think in terms of 5 years or 10 years—and of course, that’s probably a kind of childish encapsulation.

Indeed, with AI, three months sounds like a decade.

Yeah, the goalposts are not only moving left and right, they’re moving up and down! They’re moving in dimensions people aren’t even aware of!

. . . So, you know, maybe I should just quit while I’m ahead! [laughs]

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

(23)

Report Post