Columnist David Rodnitzky explains why he believes the latest Facebook privacy scandal may be overblown.

There is a common trope in movies — the all-knowing, or omniscient, supervillain. Take the Joker in “The Dark Knight.” At the beginning of the movie, he pulls off a bank heist, manages to time it perfectly and escapes in a school bus by merging into a bunch of school buses that he somehow knew were going to be passing the bank on a field trip at the exact time he was ready to leave the bank!

In real life, we often attribute omniscience to people and companies when the truth is much more, well, normal. Such is the case with the uproar over Cambridge Analytica, the data mining company used by the Trump presidential campaign to create psychographically targeted ad campaigns on Facebook.

The outrage over Cambridge Analytica goes something like this: A Cambridge University professor launched a popular “personality quiz” on Facebook called “thisisyourdigitallife” which was taken by 270,000 people. By using their Facebook IDs to take the quiz, they gave their consent for the app to access certain information about them, as well as information about 50 million of their friends whose privacy settings allowed it. Because everyone loves a free quiz!

Though the app deployment and data collection were done in accordance with Facebook’s rules, the scientist, Aleksandr Kogan, eventually took that information and gave it to Cambridge Analytica. That’s where things started to go wrong.

The firm, which works on political campaigns and was involved in both the anti-Brexit movement in the UK and President Trump’s election campaign, then added additional data to create profiles for Facebook users. Those profiles were then used to microtarget ads designed to influence political opinions leading up to the 2016 election. And — according to the Company itself and many pundits — this worked amazingly well and swung the election over to Trump.

In a secret recording made as part of an undercover investigation and reported on by The Guardian, the company’s head of data, Alex Tayler, said, “When you think about the fact that Donald Trump lost the popular vote by 3m votes but won the electoral college vote that’s down to the data and the research.”

It all sounds so Big Brother. Evil data nerds who use our own personality traits against us! Delete Facebook!

In this case, truth is much more boring than fiction. And that’s because Cambridge Analytica was not nearly as omniscient as they (or the media, or Donald Trump) would like you to believe.

And I have personal proof of their fallibility!

Cambridge Analytica’s data is questionable at best

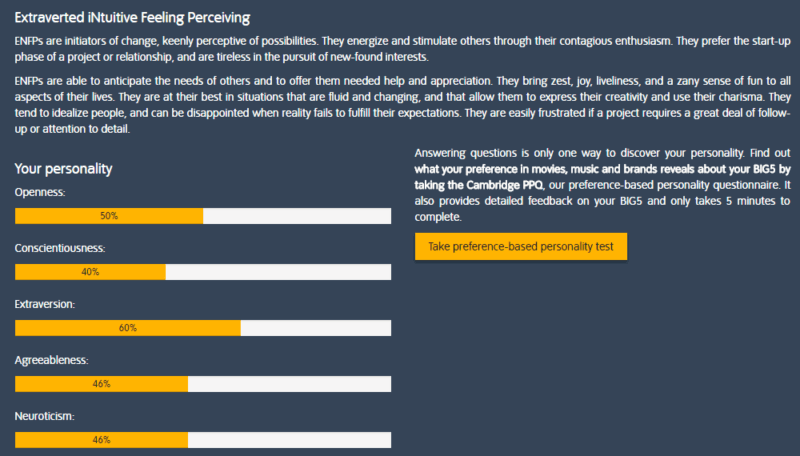

Let’s start with the first assumption of omniscience: the accuracy of Cambridge Analytica’s psychographic profiles. I took a demographic prediction test from Cambridge University that Financial Times reports was the foundation of Cambridge Analytica’s data. You can do it, too (Note: You have to give them permission to look at your Facebook and Twitter files). Here’s what they got absolutely right on my demographics:

- I am liberal.

And here’s what they got wrong:

- I’m a woman (“Your digital footprint is fairly androgynous; it suggests you’re probably Female but you don’t repress your masculine side”).

- I’m 28 years old (I wish).

- I have low leadership potential (Not saying I am great here, but I am a CEO . . .).

- I’m Christian or Catholic (only a 2 percent likelihood that I am Jewish, according to their data).

- My education is probably either in engineering or psychology (I’ve never taken a class in either).

- I’m single (married for 11 years).

Not too impressive, is it?

The more detailed personality test on the site came out more or less accurate (You have to answer 100 questions, so I’d hope it was accurate) — but it’s hard to see how these results could dramatically impact an advertiser or politician’s ability to persuade me.

Even the best microtargeting isn’t foolproof

But hey, let’s assume that they nailed my demographics and personality. What next? If you assume omniscience, Cambridge Analytica would create highly targeted ads that played to my personality traits and demographics to sway me toward a particular candidate. Maybe some fake news post about how Hillary Clinton wanted to shut down the Iowa Football program? (Their system seemed to put a lot of weight on the fact that I was a fan of the Iowa Hawkeyes.)

While I do agree that psychographics and demographics are valuable, they (a) aren’t a secret sauce unknown to savvy online marketers and (b) aren’t powerful enough alone to sway an election.

At least a couple of times a month I get a call from an ad tech vendor who wants to sell me some form of hypertargeted advertising. Be it geotargeting down to a specific store or airport or psychographic data like the stuff that was allegedly so valuable to Cambridge Analytica, this data is readily available.

Heck, Facebook has dozens of data partners that you can access directly from the advertising UI (though they have now announced that they are sunsetting third-party data partners as a result of this controversy). Here’s but one example: people who buy bakery goods more than the average person.

Obviously, if you happened to be selling bakery goods, you are going to want to target these users. And you’d think that if you combined this psychographic data with geographic data (perhaps people within a mile of your bakery), you’d have an amazing conversion rate, right? Well, it depends on the definition of amazing.

Compared to generic targeting of everyone in the US, microtargeting is going to work a lot better. But a successful microtargeting campaign might have a 5 to 10 percent conversion rate at best, which means that 90 to 95 percent of your targets aren’t going to buy from you despite being your perfect potential customer.

And let’s remember that, in this example, you’re not trying to get someone to switch from buying bread to, say, dairy. Insofar as you get 5 or 10 percent of the audience to buy from you, you are mostly enabling a change in brand preference, from their current bakery choice to you. The saying, “You can’t sell ice to an Eskimo,” seems apropos here.

Going back to Cambridge Analytica, my guess is that their ads may have had some impact on solidifying a person’s opinion, e.g., getting someone who was already leaning toward Trump to become a more solid Trump supporter. But I find the notion that these ads somehow hypnotized voters a la “The Manchurian Candidate” into doing something that they weren’t likely to already do anyway a bit much.

And it’s not like the rest of the political universe wasn’t using the same techniques. Indeed, the Obama campaign was heralded for its data savviness in connecting with potential voters and also used Facebook profile information to target ads (though, to be clear, the Obama campaign didn’t violate Facebook’s terms, as Cambridge Analytica did).

The two sides of targeting on Facebook

Someone smarter than me once said, “If you are getting something for free on the internet, you’re the product.” Facebook, Google and YouTube are all free because these platforms monetize their content through advertising. And advertisers pay top dollar to run campaigns on these platforms because of the rich microtargeting opportunities brought about by all the data that is collected about users.

Targeted advertising, however, is not just a cash cow for platforms; it actually improves the user experience as well. Think about TV advertising. There’s a reason that most households now have a DVR — so they can skip the broadly targeted ads that are almost always irrelevant to them. So even if only 5 percent of users end up buying a product advertised on Facebook or Google, most users still find the ads relevant, which isn’t the case for traditional media.

Google and Facebook have revolutionized advertising by making the ads a relevant part of the user experience. They do this by rewarding advertisers who generate the highest click-through rates (CTR). And the best way to generate high CTRs is to microtarget.

Take away microtargeting and Google and Facebook will be left with two choices: charge users to access their platforms, or serve a lot more less-relevant ads. Given these options, I’m pretty certain that most users would prefer to have some of their data sold in exchange for a free, more relevant experience.

This does not mean that Facebook and Google should have an unfettered right to collect whatever data they can from users and sell it in any way they see fit. There’s a balance that needs to be found between privacy and capitalism. But I generally believe that these companies — perhaps with very limited guidance from the government — can figure it out.

So, yes, we need to find ways to prevent rogue actors from abusing social media. But, no, we don’t need to panic and enact sweeping changes that penalize all of the legitimate (and, again, relevant) advertisers that use data responsibly because of a few bad actors.

As Shakespeare noted, “The fault is not in our stars, but in ourselves.” When we try to blame omniscient boogeymen for political outcomes we don’t like, we may feel better about ourselves, but we aren’t actually solving any real problems.

Opinions expressed in this article are those of the guest author and not necessarily Marketing Land. Staff authors are listed here.

Marketing Land – Internet Marketing News, Strategies & Tips

(89)

Report Post