By Eva Galperin

Roe v. Wade is no more, but this is not 1972, the year before it was passed. In some ways, it’s even worse.

When the Supreme Court ruled last week that banning abortion is not unconstitutional, abortion immediately became illegal in several states with “trigger laws” primed to take effect with just such a ruling. It’s about to become illegal in several more states in which previously passed laws restricting abortion had been blocked by federal courts.

Millions of people are about to lose access to safe, legal abortions, and those who provide abortion access or support will face consequences ranging from civil suits to arrest in some states. These are grim times for abortion access.

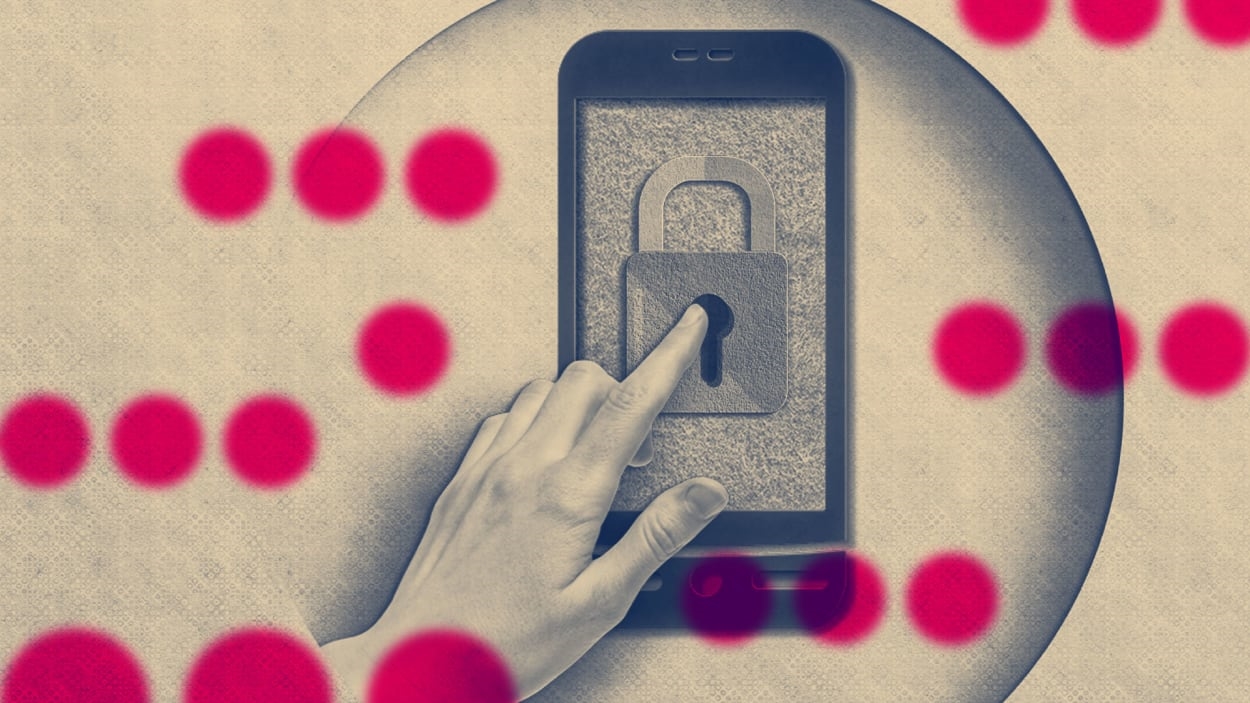

And the forecast is even more grim because we now live in an era of unprecedented digital surveillance. I’ve spent most of my career helping to protect activists and journalists in authoritarian countries, where it is often wise to think several steps ahead about your digital privacy and security practices. Now, we must bring this mindset back within our own borders for both people providing abortion support and people seeking abortions.

The first step is operational security. Abortion providers, the staff and volunteers of abortion support networks, and those seeking abortions must immediately take steps to thoroughly compartmentalize their work and health from the rest of their digital lives. That means using aliases, using separate phones and emails, downloading a privacy-protecting browser, and being very cautious about installing applications on personal phones.

For people who are pregnant, it is important to start with an understanding of the existing threats. People who have already been prosecuted for their pregnancy outcomes were surveilled and turned in by people they trusted, including doctors. The corroborating evidence included Google search histories, texts, and emails. It is time to consider downloading Tor Browser to use for searches relating to pregnancy or abortion, using end-to-end-encrypted-messaging services with “disappearing messages” turned on for communications, and being very selective about who can be trusted with information about their pregnancy.

Also, it is important to look to the future and reconsider the treasure troves of data we create about ourselves every day—because these now could be weaponized to use against us. People who may become pregnant should rethink their use of unencrypted period-tracking apps, which collect data that could be subpoenaed if they are suspected of aborting a pregnancy. They should use only an encrypted period-tracking app, such as Euki, which stores all of their user information locally on the device; but beware that if that phone is seized by the courts, the stored data may still be accessible to them. Also, people who become pregnant should carefully review privacy settings on all services they continue to use, and turn off location services on apps that don’t absolutely need them.

But right now, the biggest responsibility lies with the tech industry. Governments and private actors know that intermediaries and apps often collect heaps of data about their users. If you build it, they will come—so don’t build it, don’t keep it, dismantle what you can, and keep the data secure.

Companies should think about ways in which to allow anonymous access to their services. They should stop behavioral tracking, or at least make sure users affirmatively opt in first. They should strengthen data deletion policies so that data is deleted regularly. They should avoid logging IP addresses, or if they must for anti-abuse or statistics, do so in separate files that they can aggregate and delete frequently. They should reject user-hostile measures like browser fingerprinting. Data should be encrypted in transit, and end-to-end-message encryption should be enabled by default. And companies should be prepared to stand up for their users when someone comes demanding data—or, at the very least, ensure that users get notification when their data is being sought.

There’s no time to lose. If I’ve learned anything from a decade and a half working with vulnerable populations in authoritarian countries, it’s that when things start to go wrong, they will get worse very quickly. If tech companies don’t want to have their data turned into a dragnet against people seeking abortions and people providing abortion support, they need to take these concrete steps right now.

It is not an option to leave frightened people to figure out their own digital security in a world where it’s hard to understand what data they’re creating and who has access to it.Tech companies are in a unique position to understand those data flows and to change the defaults in order to protect the privacy rights of this newly vulnerable class of users.

The Supreme Court rolled back rights by half a century on Friday, but now is not the time to shrug and say it’s too late and nothing can be done. Now is the time to ask hard questions at work. You hold the world’s data in your hands, and you are about to be asked to use it to be “repression’s little helper.” Don’t do it.

While others work to restore rights that were so callously stripped away, good data practices can help tech companies avoid being on the wrong side of history.

Eva Galperin is the the director of cybersecurity at the Electronic Frontier Foundation.

(25)

Report Post