It is ironic that Rupert Murdoch’s News Corporation has complained to the European Commission about Google – but it has become like a giant octopus, gobbling up and stifling everything

It takes one to know one. Along with Amazon, Google is perhaps the most transformative of all the high growth businesses to have emerged from the communications revolution of the past 20 years, sweeping all before it and like some kind of giant wrecking ball, laying waste to many of the established economic powerhouses of the past. Success on such a scale is bound to generate resentment and complaint, and just lately, Google has been the subject of a veritable barrage. What’s more, quite a lot of it is justified.

There is none the less a certain irony in the fact that battle has now been joined by Rupert Murdoch’s News Corporation. In a no-holds-barred missive, his chief executive, Robert Thomson, has written to the European Commission complaining about a “cynical management … willing to exploit a dominant market position to stifle competition”.

When I heard about this, I imagined for one glorious moment that someone had got hold of an internal News Corp memo, detailing Mr Murdoch’s own private agenda, for this is a man who has spent much of his life ruthlessly pursuing the holy grail of monopoly. Both in UK national newspapers and pay TV, he came pretty close to achieving it.

Yet against Google, Mr Murdoch’s achievements pale. It must stick in the craw. At nearly $400 billion, Google is capitalised at four and a half times the combined market worth of Mr Murdoch’s Twentieth Century Fox and News Corp, and an astonishing 40 times the value of News Corp alone, the holding company for all Mr Murdoch’s newspaper interests, including the Wall Street Journal, the Sun and The Times.

All business, if it is honest about its motives, aspires to monopoly, for it is very much part of the dynamic of capitalism that companies attempt to out-trade or otherwise destroy competitors. Mr Murdoch was once a master of the art.

Like Google, Sky was originally just a start-up. Fox, too, began from virtually nothing. It was Mr Murdoch’s drive and vision that made them what they are today. Both are phenomenal entrepreneurial achievements. That they are now being eclipsed by Google and other new media upstarts will surely hurt. And that Mr Murdoch is for a change off the front foot and onto the back, will feel strange and unnatural to him. By character, he is an attack dog. Defence is not his game. But that he is turning for help in countering the new menace to the very people he has spent a lifetime fighting – government regulators – is perhaps the strangest thing of the entire business. Complaining to regulators about unfair competition is what business losers do, not the winners.

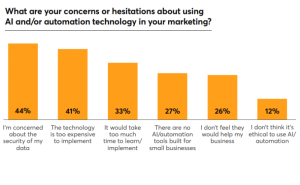

None of this is to argue that News Corp has no case. Google has become like a giant octopus, gobbling up and stifling everything around it. Its tentacles are seemingly everywhere. Mr Thomson has timed his letter to perfection, for we seem to be at one of those tipping points, where growing concern about an emerging business monopoly may well turn to destructive action against it. If Google has a fault, it is lack of transparency. Despite its manifest power, nobody outside a small core understands how its algorithm works, or how its rankings are established, still less how it manages to achieve a gross profit margin of an astonishing 50 to 70 per cent.

Google thought it had secured a deal with European regulators that would answer its critics. But following a tsunami of complaint from the German publishing establishment, the Commission is reconsidering, and now threatens Google with something very much worse. Mr Thomson’s intervention adds to the pressure for much harsher action.

In the end, however, it is more likely to be size and innovation that will be Google’s undoing than a regulatory crackdown. Eventually, all successful organisations become too big to manage. They get comfortable, complacent and fat, and don’t see the next big thing coming until it hits them in the face. Even the most successful business models eventually mature and decline, Tesco being only the most recent example with its out-of-town mega stores, now increasingly redundant.

I still vividly recall a World Economic Forum nightcap with Microsoft’s Bill Gates, then at the height of his power and influence, during which he opined that search engines like Google were undoubtedly a phenomenon, but he wasn’t yet convinced they were a proper business. A similar moment of complacency and misjudgment will eventually engulf Google.

In Mr Murdoch’s neck of the woods – news distribution – social media has already taken over from “search” as the primary point of access. In other spheres too, challenger platforms to Google are popping up all over the place, and because Google is no longer seen as independent, preferring to push users to its own profit centres, they will eventually thrive.

Even so, regulators can be instrumental in speeding up the process of corporate decay. IBM never recovered from its 13-year fight with antitrust regulators. By the time the case was dismissed as “without merit”, the world had moved on. IBM – obsessed with the legal battle – had not, and paid the price. The same is partially true of Microsoft, whose decline as king of the techs coincided almost exactly with an all-out assault by US and European competition regulators.

So far, it’s been most unwise to bet against Google, but Mr Thomson’s letter may in time be seen as the company’s high water mark.

Telegraph Columnists: daily opinion, editorials and columns from our star writers

(388)

Report Post