Social Media Metrics

Social Media Metrics

Is it true that there’s one metric to rule them all?

(May 23, 2015), I attended an analytics session at the Modev MVP conference — which is a great group of folks and an excellent learning experience for product managers. The panel consisted of key folks from NPR, Uber, OPower, and other companies discussing how they’re using metrics to run the business.

Someone suggested you should measure between one and three metrics, which makes a lot of sense if you’re a time-crunched startup, but struck me as a little dangerous. But, as the question of metrics moved down the panel, everyone agreed you should have a very limited set of metrics you analyze — popular metrics included new customers or other growth measures.

Finally, the question made it toward the end of the panel where John Mark Nichols, Sr. Director of Product, Marketplace Efficiency at Uber, sat. He said what I’d been thinking through the earlier discussions.

There are problems with the “one metric to rule them all” mentality. And, the biggest problem is you analyze metrics to provide guidance on management decisions, not just as a yardstick of how well you’re doing.

One metric to rule them all

If you Google “one metric to rule them all” you’ll get a wide divergence of opinions about whether there is a single metric or multiple metrics you should analyze as part of evaluating the success of your business.

While MOZ comes out in favor of a single metric, their metric is actually an algorithm that provided multidimensional information to both measure success and provide insights for decision-making. So, despite their one metric to rule them all notion, they really advocate a combination of factors to assess your business. I’ll talk a little more later about their algorithm and why it makes sense.

Seth Levine at VC Adventure recognizes the decision-making value of using multiple metrics — potentially hundreds of metrics specific to each group within the organization. He acknowledges the common practice of rolling up these decision-making dashboards into core metrics used by the C-suite to monitor the overall health of the organization and for strategic planning.

Despite his belief in a plethora of metrics for decision-making, Levine believes organizations should develop one metric to rule them all. He’s done an exercise with many CEOs asking them to come up with this singular metric, which generally results in an answer that really doesn’t hit on the most important metric. Here’s more about what Levine says about one metric to rule them all:

At the core of what you do as a company, underneath the veneer of the business itself is typically an underlying data point that is at the heart of the product or service that you’re providing. That may be the number of domains that you manage, the number of emails that you send out daily, the number of unique website visitors that your business generates. Rarely is this number an input, nor is it generally a forward looking statistic. It’s also likely not a financial number – you won’t find this metric on your income statement. It’s generally an operationally derived output to the running of your business. Surprisingly (and this is part of the power of this exercise) in many cases it’s not something that you’re already tracking on your highest level dashboard.

He encourages businesses to go through the exercise as a means to improve not only management of the business, but as a chance to remember what the business is — at its core.

Levine isn’t alone when it comes to a belief in one metric to rule them all. In his keynote at Lean Conference 2014, Ash Maurya, who wrote the book Running Lean, argues for distilling hundreds or thousands of metrics down to a single metric (or, at most a small handful of metrics). This is surprising for a methodology heavily grounded in management science.

Not to be outdone by their cousins Lean, Agile proponents like Wes Williams disparage startups who think they can capture everything they need in a single metric or two.

How to use one metric to rule them all

I don’t believe it’s possible to have one metric to rule them all.

Even in the C-suite, where you’re interested in a less granular view of firm operations, you need more than a single metric — unless that’s a composite metric like the one developed at MOZ. It’s important to note the MOZ metric is designed to assess content performance, but, with adaptation, you could use it to assess whatever core function you desire.

Not only is the metric a composite, which makes it preferable in my mind to one metric to rule them all, it uses a number of other tactics to develop a single metric that provides a ton of information.

Let’s take a look at the features of the MOZ metric and what makes it good.

Combines key metrics

For content, key metrics include Google Analytics, page metrics, and social signals (Tweets, RT, Shares). These metrics align perfectly with those critical for content success — ie. they drive visits through organic (these metrics are key page elements included in the Google Search Algorithm) and social.

If your company wants to assess overarching success, what key metrics should you combine?

- Sales (or year over years sales if there’s a seasonal component)?

- Operating expenses?

- Customer satisfaction?

- Returns?

- Loyalty?

Weight metrics

Metrics aren’t on the same scale so simple addition distorts the resulting metric and skews interpretation in the wrong direction. Instead, weight metrics to ensure you’re comparing apples to apples.

In the example above, sales might be measured in millions of dollars, while customer satisfaction might exist on a 10 point scale.

An effective way to weight factors is to turn them into percentages rather than combining raw numbers. Thus, customer satisfaction might be 80 percent and returns 13 percent.

Another weighting consideration is a function of the impact of a factor on some desired performance measure. This type of weighting requires regression analysis to assign β-values (or β-weights) to each factor.

Use gap analysis

Image courtesy of MOZ

This tactics actually comes from accounting where you develop projections or expectations. You then compare actual with expected and model the gap (or difference between actual and expected). Small gaps represent adequate performance, while large gaps (primarily negative ones) reflect poor performance.

We call this “management by exception” meaning you pay close attention to large gaps because they reflect problems and ignore small gaps as representing suitable performance.

Of course, if expectations are set artificially low, performance appears adequate when, in fact, it’s poor. Tying performance evaluations closely with gap analysis may result in managers gaming the system. The best expectations represent historic performance averages.

Obviously, you’d want to automate the process by integrating your data sources into a spreadsheet containing the macros necessary to perform the calculations.

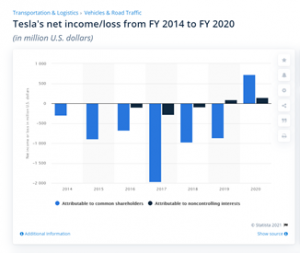

Plot over time

Performance metrics make so much more sense when plotted over time and viewed as trends rather than point measures.

Observing the trend line, any major deviations represent positive or negative outcomes and bear further scrutiny. Obviously, since the composite measure is comprised on a number of individual metrics, further exploration should yield insights into which metric or metrics are responsible for deviations and decisions made about how to optimize performance moving forward.

Uses a graphical interface

Instead of expecting optimal decisions based on row upon row of text and numbers, display data using a graphical interface — a picture is truly worth a thousand words.

Notice in the spreadsheet to the left, the one metric to rule them all is color coded to alert analysts when the metric goes out of whack. Now, instead of praying that deviations penetrate the concentration of a busy executive, he/she can quickly find problems at a glance. Of course, I would have coded really low performers red rather than leaving them uncolored.

(244)

Report Post