By Marcus Baram

May 14, 2022

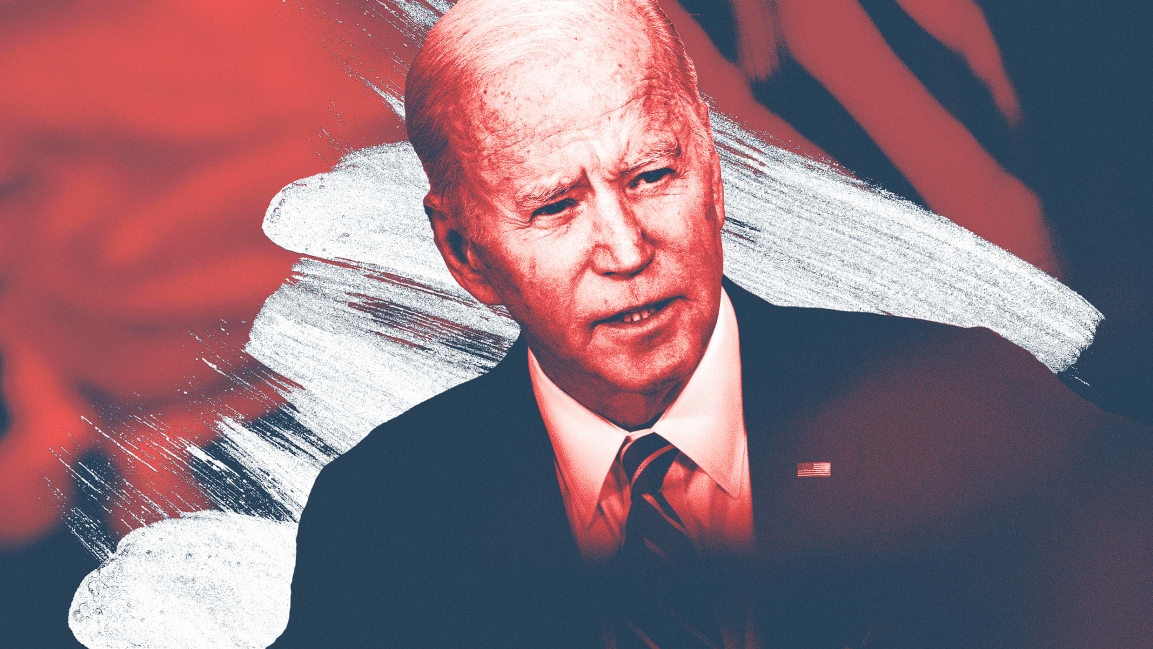

After decades of decline in overtime pay, the Biden administration is considering action to sharply expand access in a time of high inflation. This is the second article of a four-part series examining the 40-year effort by big business and elected officials to deny Americans extra pay for extra work.

An impeached Republican president gives way to a labor-friendly Democrat with an ambitious agenda to expand workers’ rights from the White House. The Democrat wants to extend overtime wages to additional workers, but beset by rising gas prices and high inflation, the Oval Office comes under intense pressure from corporate lobbyists and fiscal conservatives in his own party. Fearful of the cost to companies and the risk of harming the economy, they want the president to slow down and shrink his vision of expanding overtime.

President Jimmy Carter’s efforts to expand overtime eligibility in the 1970s are notable today, as Joe Biden’s administration seeks to boost workers’ buying power in the face of inflation driven up partly by pandemic economic stimulus, geopolitical instabily, and shocks to energy markets. Then, as now, the Labor Department recognized that providing working-class Americans time-and-a-half pay when they put in more than 40 hours a week would help them to cover soaring energy costs and cope with higher grocery bills.

Under Carter, overtime was limited to workers earning less than $8,060 per year—or a maximum of about $4 per hour. The Labor Department proposed increasing that threshold over time from $11,700 in 1981 to $17,940 by 1983, equivalent to $37,350 and $52,282, respectively, in today’s dollars.

But the risk of even more inflation led Carter’s White House to shrink the proposed expansion and to delay the first stage of its enactment until a hoped-for second term in 1981. Instead, Ronald Reagan became president and his corporate-friendly administration shelved Carter’s new overtime rules, and full-time workers earning an hourly wage of a little above $4 (or more) saw no increase in pay when they did additional work.

Throughout the 1980s, 1990s and the 2000s, the overtime threshold didn’t come close to keeping up with inflation. While the maximum income threshold for overtime eligibility has since been raised to $35,000, tens of millions of workers have lost out on potential overtime wages as their buying power diminished.

That’s because $100 went more than four times further in 1979. As for the many workers who earned more than the pay threshold, the vast majority of them never had any federal guarantee they could earn overtime pay.

Fast forward to 2022. The Biden administration is contemplating a revamp of overtime rules, and their enforcement. Labor Department officials recently met with industry groups and employee advocates to discuss possible new parameters that, observers say, will be announced in the coming months, barring a surprise. The labor-friendly Biden is also likely to propose other changes to provide overtime to some who are excluded from it because they work in fields long deemed ineligible.

But facing the highest inflation in 40 years and pushback from corporate lobbyists, it remains to be seen whether Biden will be able to deliver for millions of workers.

Workers Won Overtime, and Then Lost It Again

Paid overtime was established nationally in 1938 by the Franklin D. Roosevelt administration as part of his New Deal. In the depths of the Great Depression, it proved popular with Americans, and became fairly standard. By 1975, more than three in every five full-time salaried workers qualified.

But 47 years later, just one in 14 workers is eligible for time-and-a-half pay. This is part of why workers in many professions have less buying power today than their predecessors did in the 1970s.

The decline in overtime was driven by hardworking lobbyists representing influential industries seeking to lower costs, and lawmakers who sought to protect business interests. It was also facilitated by government officials who prioritized other issues, as well as the general lack of strong voices for workers in Washington, D.C. As Nancy Leppink, the former head of the Labor Department’s Wage and Hour Division, explains, “There is no one there to speak for the workers primarily impacted by these policies.”

This was even true, she suggests, during the Clinton and Obama administrations, ostensibly pro-labor governments that, despite their stated goals, failed to meaningfully increase the number of Americans who qualified for overtime.

This may have been due to a disconnect between administration officials’ goals and their understanding of the working world they were trying to transform. Maria Echaveste, a Labor Department official in the Clinton administration, remembers being in a large White House meeting in the mid-1990s and realizing that she and another staffer were the only ones present who had ever punched a clock at work. The lack of practical experience laboring away at such jobs left a gap between administration members’ policy aspirations and the actions they took to try to address practical challenges, such as expanding overtime pay and ending wage theft.

External events also roiled the lives of countless workers. When the incoming Obama team moved into the Labor Department’s headquarters on Constitution Avenue across the street from the U.S. Capitol Building in 2009, the nation was in crisis. The Great Recession was already pummeling the economy, spurring layoffs and further weakening unions.

Meanwhile, the Department of Labor’s Wage and Hour Division had endured steep budget cuts under President George W. Bush. Staffing losses were particularly notable at the managerial level, but they were having a tremendous impact across the board. Under President Carter, they had 1,600 investigators; Leppink recalls that by the start of the Obama presidency, there were just 700.

Resources were a big problem, too. District offices often lacked copy machines and didn’t even have phones, while staff were also handicapped by a shortage of laptop computers. Things were so bad that some employees told Leppink they had taken to hoarding office pencils. Travel budgets had also largely disappeared, she said. “If you couldn’t inspect a workplace in a day and get back to the office that same day,” she said, “those investigations didn’t happen.”

In those circumstances, labor activists called on the Obama administration to help the nation’s workforce by raising the overtime-salary threshold so that even white-collar managers could qualify for overtime. At the time, the threshold was $23,600, far below the national median personal income of $41,548, meaning that only a small percentage of workers ever received time and a half.

Historian Samuel P. Huntington painted a grim picture of workers in the United States in 2005. Americans, he wrote, “work longer hours, have shorter vacations, get less in unemployment, disability, and retirement benefits, and retire later than people in comparably rich societies.”

The U.S. stands apart for other reasons as well. Canada, Great Britain, and the European Union cap the maximum length of a work week at 48 hours. In the U.S., there is no hard limit. Such differences help explain why American workers put in an average of 1,767 hours per year versus 1,687 hours for the 38 mostly wealthy countries that are members of the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). So Americans work the equivalent of two additional weeks of work every year.

No, We Can’t

While the Obama administration was sympathetic, it was distracted. In a politically divided capital, the administration invested most of its energies getting the Affordable Care Act passed and pulling the country back from the economic brink during the Great Recession. On the labor front, it seized on priorities, such as bolstering the rights of independent contractors in a rapidly expanding gig economy.

“The Obama team was very cautious in its first term,” says Leppink, explaining that her staff was allowed to begin researching ways to update the rules, but that proposing actual changes was discouraged until Obama’s second term. But, she says in hindsight, “If you wait too long, you put yourself in jeopardy.”

Finally, in March 2014, over a year into his second term and hobbled by an obstructive Republican majority in Congress, Obama announced that the Labor Department would revamp the overtime-wage rule to lift the salary threshold to $47,476. The doubling of the maximum income able to potentially access overtime was dramatic, but it was also in line with historical precedent. In 1975, President Gerald Ford’s Labor Department set the threshold at $8,060, which is the equivalent of $43,600 in today’s dollars. That was high enough for more than half of full-time salaried workers in the 1970s to be eligible for overtime. Obama’s increase, by contrast, would have covered about 34 percent of full-time salaried employees.

The proposal prompted a frenzy of lobbying by business and worker-advocacy groups; the agency’s website was flooded with 154,712 comments in just 60 days. Industry groups committed to shooting down or weakening the proposal issued their own studies claiming to show a devastating impact on businesses.

The American Action Forum, a conservative think tank, argued that “the worker benefits are quite limited, and the regulatory costs on businesses are substantial,” claiming that only 825,000 of the 4.2 million newly qualified workers would regularly benefit from the rule and that businesses would face almost $3 billion in compliance costs.

Forces on both sides worked around the clock to pressure the administration. When the liberal Economic Policy Institute heard that the Labor Department was considering only modest increases to the salary threshold, Ross Eisenbrey, a vice president at EPI, told The Washington Post, “We raised a ruckus.” The Labor Department agreed to raise it higher.

Eisenbrey pushed the administration to expand the number of Americans who qualified for overtime by tightening the rules exempting certain jobs, like fast-food managers, from overtime. The agency applies what it calls a “duties test” that allows for overtime exemptions. The concept originally applied to bona fide executives, administrators, and professionals; over time, it came to be misapplied, he argued, to exclude many other workers who should be eligible for additional pay.

“If you really are an executive, you should be paid an executive salary, not $23,600, which is less than the poverty level for a family of four,” Eisenbrey wrote in a post for the Economic Policy Institute. “The current regulations are out of date and result in millions of employees working long hours without extra pay.”

Meanwhile, Labor Department officials from the George W. Bush administration, who had signed on with prominent law firms after his presidency, took part in influence campaigns on behalf of large corporations and industry groups. This was, according to The Washington Post, about “helping major employers to head off a drastic change” to policies they had helped administer when Bush was in the White House.

Such efforts weren’t just about business interests. Nonprofit groups, such as the YMCA and Habitat for Humanity, which both feared the impact on their bottom lines, also opposed the changes. In a brief filed by the U.S. Public Interest Research Group, the longtime progressive organization argued that doubling the threshold would force them to “hire fewer staff and limit the hours those staff can work.”

The pressure, particularly from the business community, was effective—”strong employer-lobbying efforts yielded important changes to the proposed overtime rule,” bragged the Society for Human Resource Management, a major industry group, in 2015.

The Obama administration was forced to reduce the planned increase in the salary threshold and to dial back efforts to limit the ability of companies to exempt employees from overtime by giving them minimal managerial responsibilities. But it wasn’t enough, and in the end, a coalition of hundreds of business groups and 21 states sued the administration, claiming that it had exceeded its statutory authority by raising the salary threshold so high. On November 22, just two weeks before the new overtime policy was set to take effect, Judge Amos L. Mazzant III of the Eastern District of Texas overturned the rule.

Workers didn’t immediately feel the impact of the defeat of the Obama administration’s effort since it was never implemented. But it would cost workers a great deal. Canceling the rule would lead, according to a 2016 Congressional Budget Office estimate, to the loss of $570 million in earnings for affected workers in 2017 alone. Between 2017 and 2022, the predicted loss was $2.6 billion.

The fight over overtime brought key problems with the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) to the fore, most notably that its regime of wage and hour laws didn’t apply suitably to large swaths of the 21st century working world in which gig workers and remote employees were becoming increasingly common. The FLSA was written for archaic job categories like coppersmiths and steam railroad porters.

This is part of why many people in the field would like to modernize the law, but face challenges in doing so. “There is nothing that prevents a group of lawmakers from amending the [Fair Labor and Standards Act] and providing for the elimination of the duties test, and establishing an automatic accelerator for the salary threshold,” says workplace lawyer Michael Lotito. “But that is probably more difficult than convincing Putin not to invade Ukraine. It’s very difficult. Congress has proven itself incapable of coming together on matters that affect the workplace.”

It all raises questions about whether President Biden, who faces the worst inflation since the 1970s, along with pressure from business lobbyists, will deliver access to overtime for millions of workers—or whether, despite the best intentions, his effort will come up short, like those of Presidents Carter, Clinton, and Obama.

Copyright 2022 Capital & Main.

This story is part of a series on overtime produced by Capital & Main in partnership with the McGraw Center for Business Journalism at CUNY’s Newmark Graduate School of Journalism and Type Investigations, with support from the Puffin Foundation.

(30)

Report Post