— November 7, 2018

It’s the early 1980s. You’re in charge of a fledgling ESPN, and you have two choices:

- Add more college basketball—you’re highest-rated programming—to the schedule.

- Stick with the skiing and billiards you’ve aired for years (because you couldn’t afford anything else).

Which creates the more profitable programming bundle?

ESPN stuck with the esoteric sports. And because of that choice, the ESPN family of channels now consumes a double-digit percentage of your cable bill.

Here’s what they knew: To boost subscriber fees, they needed to maximize the number of people who would pick up the phone and call the cable company if, during a tense negotiation, the provider threatened to drop ESPN. Hence, it benefited them to capture the widest possible market—even at the expense of ratings.

For ESPN and others, bundling strategy can be deceivingly complex. It’s easy to assume that you’ll succeed if you simply pick two or three items, sum their value, and offer them at a slight discount. But if you want bundling to work—and work consistently—you need a far more thoughtful approach.

What qualifies as a “product bundle”?

The definition of “product bundling” varies. According to some, newspapers are a bundle of articles sold as a single unit, just as albums are a bundle of songs. (So is a concert a bundle, too?)

This flexible definition can yield endless debate about what constitutes an individual unit for sale or whether an offer is a bundle versus a “cross-sell” or an “add-on.” We’ve tried before to differentiate the three, all of which we bundle(!) into the category of “upsells”:

- Bundles. Two or more complementary products added to the cart from the product page or checkout, usually sold at a discount.

- Cross-sells. A product that complements an existing purchase but is from a different category (or vendor).

- Add-ons. The extras—protection plans, tech-support subscriptions, or product training—that offer peace of mind.

Regardless of where you draw the line, there are two key delineations within product bundles:

1. Product bundles versus bundle pricing.

- While bundled products are often sold at a discount, a special price is only one of several potential motivators. (And, as it turns out, one of the hardest to make successful.)

2. Pure bundles versus mixed bundles.

- Pure bundles are available only as a bundle. Think of Adobe Photoshop: You don’t get to include the magic wand tool but omit the Gaussian blur filter.

- Mixed bundles are available for purchase separately and as a bundle. Think of fast-food meal deals: You can still purchase any of the items individually.

For sellers, the potential benefits of product bundling are clear—and, perhaps surprisingly, far-reaching.

How bundles benefit sellers

Most often, bundles are an opportunity to increase the average order value. One estimate from McKinsey suggests that 35% of all Amazon purchases come from recommendations (at least some of which qualify as “bundles”) and that recommendations have a success rate, according to Forrester, of around 60%.

While you can argue about which upsell bucket each recommendation falls into, the takeaway is the same: Adding related products to a pending purchase is a powerful way to grow revenue. (And, along with increasing the number of customers to your site and the number of repeat customers, it’s one of only three ways.)

There are six other, less-considered benefits, however:

1. Pricing opacity. Here’s the classic example: A $ 750-per-night hotel charges $ 10 for a bottle of water. Consumers feel ripped off. However, that same hotel room for $ 760 per night including water seems like a reasonable deal.

High-end hotels—and other big-ticket services and products—are better off bundling the cost of small items, like water, into the price of the high-value item.

High-end hotels—and other big-ticket services and products—are better off bundling the cost of small items, like water, into the price of the high-value item.

If a minor product has a price point that—justified or not—causes major friction, bundling its cost into the price for the main item can reduce its negative impact.

2. Inventory reduction. Bundles can help move stagnant inventory. There are risks to “throwing in” products (detailed in a later section), especially if that product is cheap compared to other items in the bundle.

3. Product-line expansion. Typically, purchasing individual low-cost items online has two solutions, neither of which is satisfactory: The seller subsidizes shipping but loses money on the deal, or the buyer pays more for shipping than the product itself.

Bundling products at an order-value threshold (“Orders over $ 50 qualify for free shipping”) allows ecommerce companies to expand their product lines with a solution that works for buyers and sellers.

4. Marketing simplicity. If you sell 20 products, you have to market 20 products. If you bundle them as one, you market them as one.

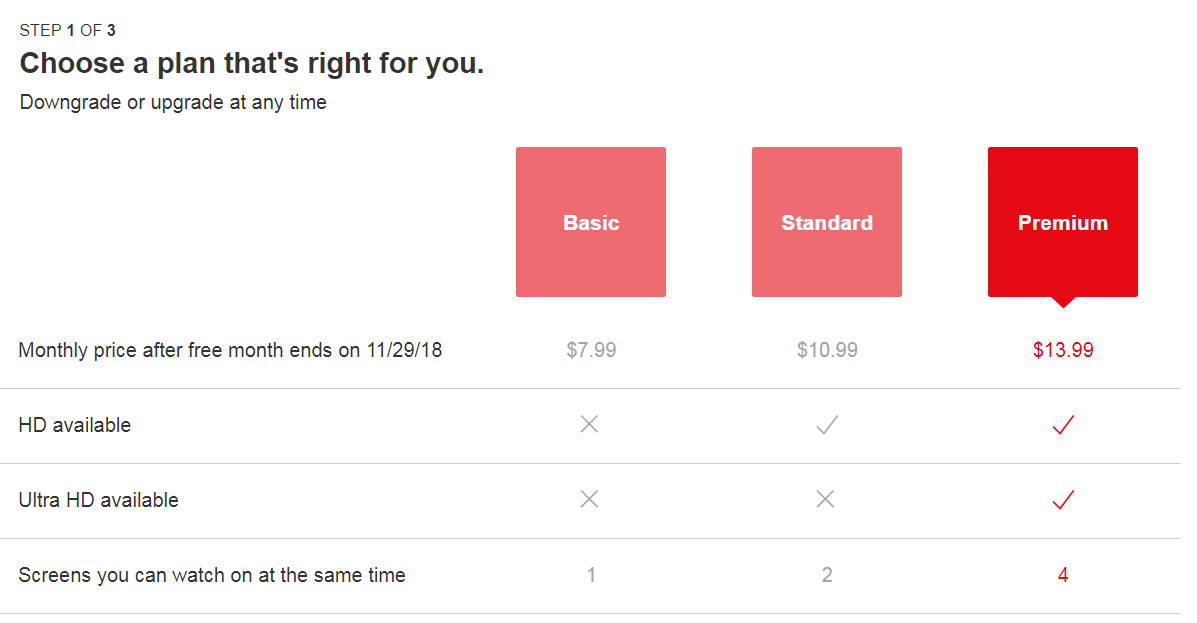

5. Increased product usage. Spotify or Netflix could price plans based on genres. Don’t need the country music catalog? Save $ 1. Never watch horror movies? Take $ 2 off your bill.

For subscription services or SaaS companies, however, bundling expands the use cases for a product. And because platforms like Netflix rely on recommendation engines—some 75% of what users watch comes via recommendations—bundling expands the potential list of recommended titles.

At a minimum, bundles encourage product sampling and exploration, which could help an acid rock aficionado discover the joys of an aria (or motivate a new software user to learn advanced skills).

6. Subsidized feature development. Bundled content (for media companies) and features (for software services) use core features to subsidize development of “long-tail” capabilities.

Even if a fraction of customers use advanced features (e.g. Microsoft Office), the increase in consumers’ perceived value—what they could do—justifies a higher price point that, in turn, funds feature development for power users.

But what do buyers get out of all this?

How bundles benefit buyers

As Roger Dooley notes, bundling reduces the “pain of paying” for consumers. Because pricing is more opaque, they’re less able to identify the “right” price (even if you are charging them $ 10 for that bottle of water) and, therefore, less anxious about paying the “wrong” one.

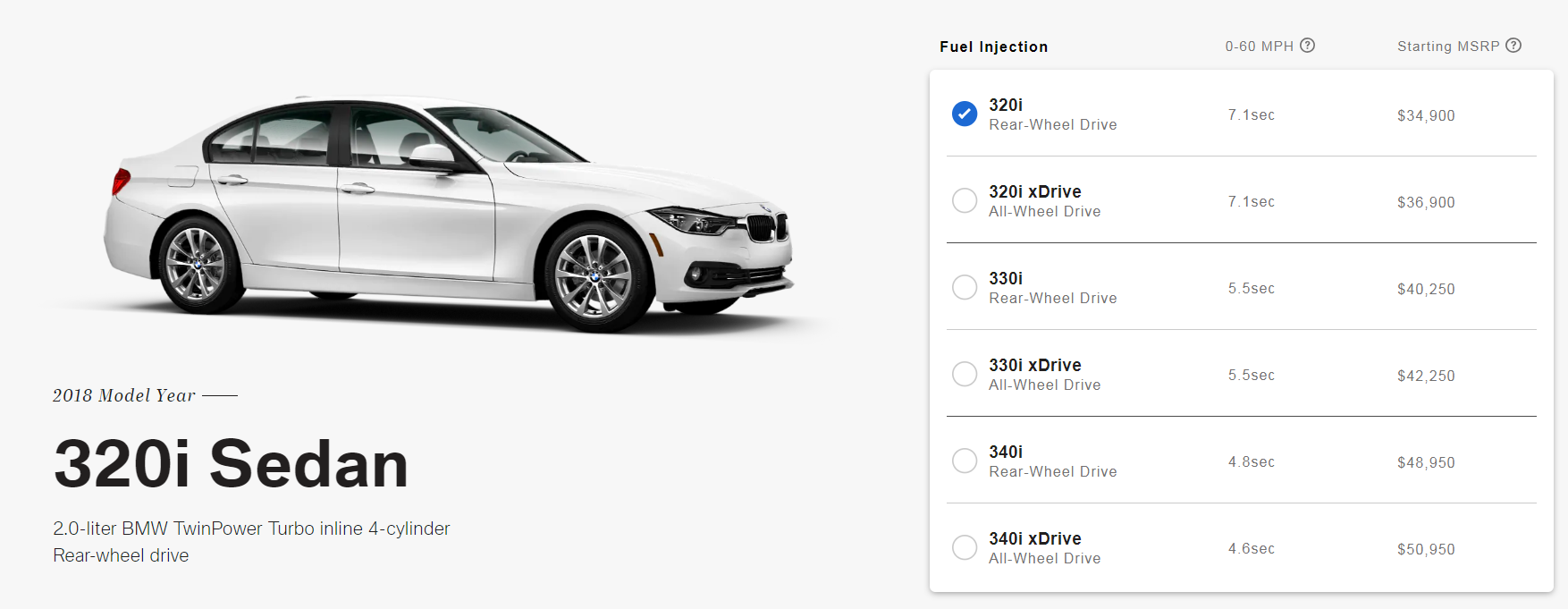

In Dooley’s example, a consumer getting the “luxury” package for a new car has no idea how much he’s paying for leather seats versus the premium sound system. The inability to price each feature frees the consumer from the cognitive burden to pass a fair–unfair judgment on every item. (Yes, this can benefit the seller, too.)

Automakers have long bundled disparate features into a handful of “packages” to reduce the “pain of paying” (and keep consumers from conducting a line-by-line accounting of every feature).

Reducing the pain of buying is increasingly important. A plethora of studies (here’s one and here’s another, but they’re everywhere) shows that most consumers research products online before buying—even on their smartphones while in a brick-and-mortar store. Omnipresent access to product comparisons and pricing knowledge balloons the pressure to find the “right” price.

When the price is known and a discount is offered, bundling helps price-sensitive consumers get what they want at a discount. As mixed and customizable bundles become more common (and better targeted), consumers enjoy more choice—they get the bundle benefits of convenience or price savings while retaining a say over what’s included.

As Anthony Tjan summarizes:

If you are the customer pushing to unbundle the package, asking for a price breakdown is almost always to your favor. Choice is a good thing for you.

Still, bundling is easy to get wrong.

When bundling products doesn’t work

While the potential business benefits of bundling are clear, the process to implement a successful bundling strategy is murky. The “presenter’s paradox” exemplifies the risks of getting it wrong.

The presenter’s paradox

In the original 2012 study, the “presenters” had two choices of what to offer hypothetical customers:

- An iPod Touch with a cover; or

- An iPod Touch with a cover and one free music download

Bundling the song download into the package should make it more valuable, right? Some 92% of presenters thought so—but they were wrong. Participants were willing to pay higher prices for the iPod Touch without the free song download.

Why? Because we subconsciously average the value of bundle components rather than taking their sum. Steve Martin of Influence At Work offers an analogy:

Much like adding warm water to hot leads to a more moderate temperature, attempts to clinch a deal by adding extra features to an already strong proposal, could mean a reduction in the overall attractiveness of that proposal. In effect each additional feature or piece of information provided serves to cheapen the overall package.

The iPod Touch wasn’t the only scenario to show the effect: Consumers were more likely to purchase a pricey home gym when a companion fitness DVD wasn’t included. Additionally, and most surprisingly, people were willing to pay $ 225 for one piece of luggage and $ 54 for another when purchased separately—but only $ 165 for the items as a bundle.

Why are we willing to pay more for less? Categorical reasoning.

Categorical reasoning

As Alexander Chernev explains:

People naturally tend to classify products as either expensive or inexpensive, and this categorization influences how they judge products. When an expensive item is bundled with an inexpensive one, people categorize the bundle as less expensive, and this lowers their willingness to pay for it.

Chernev’s research on categorical reasoning reveals further insights:

- “Simply putting the products side by side doesn’t produce a subtraction effect. That effect occurs only when the two items are considered part of the same offering.”

- “This effect is not caused by differences in the perceived quality of the bundled products and can occur when both items are of similar quality, as in a combination of a Porsche with a Montblanc pen.”

Ultimately, if a bundle inspires categorical thinking along “inexpensive” and “expensive” dimensions, your offering will suffer.

But categorical thinking applies to more than just price. As Chernev discovered, adding a salad to a cheeseburger reduces estimates of total caloric value, even though adding food could only increase calories. Categorical thinking averages the non-numeric perception of nutrition between the two items.

Our research on the presenter’s paradox and the categorical thinking that fuels it confirms its effects, albeit in a diminished form. Our findings reinforce the idea that the effect “is contextual, and likely is influenced by the value gap between the items presented and the presentation of them.”

When it comes to the risk of bundling products, there’s another factor to consider: cognitive load.

Beware of cognitive load

Cognitive load is the amount of mental energy it takes to complete a task. As we’ve written before, a high cognitive load can lead to “analysis paralysis” and make consumer decisions more difficult. Complex bundles may increase the cognitive load—even if the intention is to benefit the consumer.

For a buyer, choosing a single streaming service that bundles all content is easier than selecting the 56 subgenres you want to pay for (or, at maximum granularity, the exact songs or shows among tens of thousands).

Netflix could allow consumers to customize their access based on genre—but the cognitive load would be overwhelming.

Netflix could allow consumers to customize their access based on genre—but the cognitive load would be overwhelming.

The key to making bundles work is symbiosis—developing a product bundling strategy that benefits buyers and sellers.

How to make product bundles work

While price-based categorization can undermine a product bundling strategy, there are two workarounds: price anchoring and, if that fails, a reframing of categorical dimensions.

Price anchoring

Roger Dooley has a theory, one that helps explain why infomercials are so successful with the extras and add-ons that the presenter’s paradox warns against:

the infomercials work to establish a high anchor point (“Thousands sold at $ 199!”), and then give the consumer a lower price (“Just four payments of $ 29.99!”). By the time they start throwing in the deal-sweeteners, the price has been set in the consumer’s mind and the extra items are indeed seen as adding value. The consumer doesn’t need to take a mental shortcut to estimate value, and the categorical thinking effect doesn’t occur.

Dooley’s theory is useful for SaaS companies that choose to present annual versus monthly payment plans: A monthly payment plan may create, in the consumer’s mind, a lower price anchor that makes a lower-value freebie or bundled add-on seem more enticing.

The ideal solution, however, may be to stray from any focus on price.

Categorical thinking: Focus on benefits, not monetary value

Categorical thinking has a negative effect on product bundling when the two categories are “expensive” and “inexpensive”—the cognitive average will not help you. However, Chernev argues, there’s a way to side-step the challenge of price-based bundling:

People categorize along just one dimension at a time. So if you get people to focus on non-price attributes, the price effect will go away. For example, a shoe retailer could get customers to think of shoes in terms of comfort, durability, or versatility.

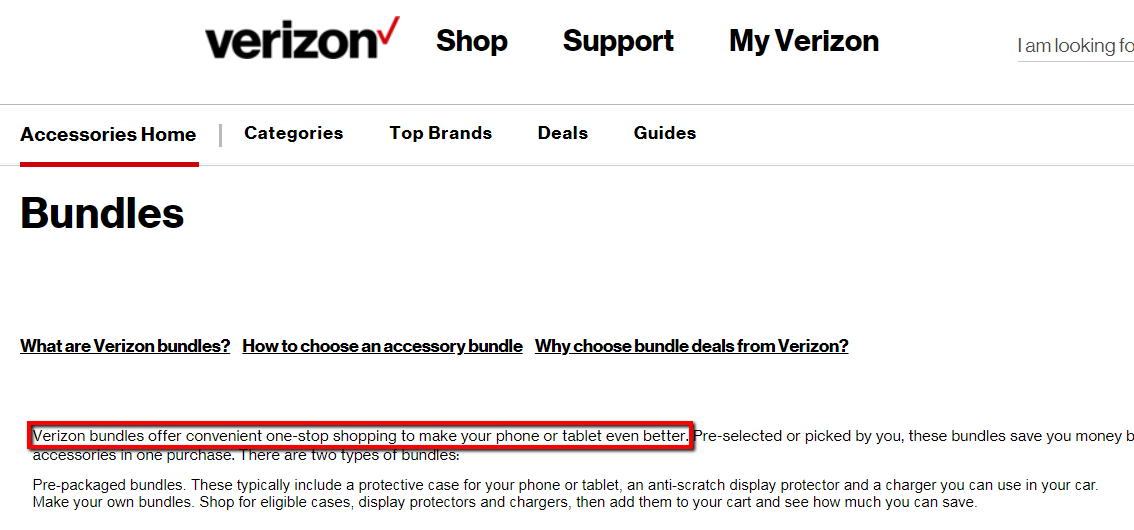

Refocusing the presentation of bundled products on non-price benefits avoids the price-based comparison. For accessory sales, Verizon could focus on price savings but instead highlights convenience and improved device performance as the primary benefits of bundling:

A focus on monetary value may work only for price-sensitive consumers who need a reason to make a purchase sooner rather than later.

Bundle pricing to accelerate the purchase

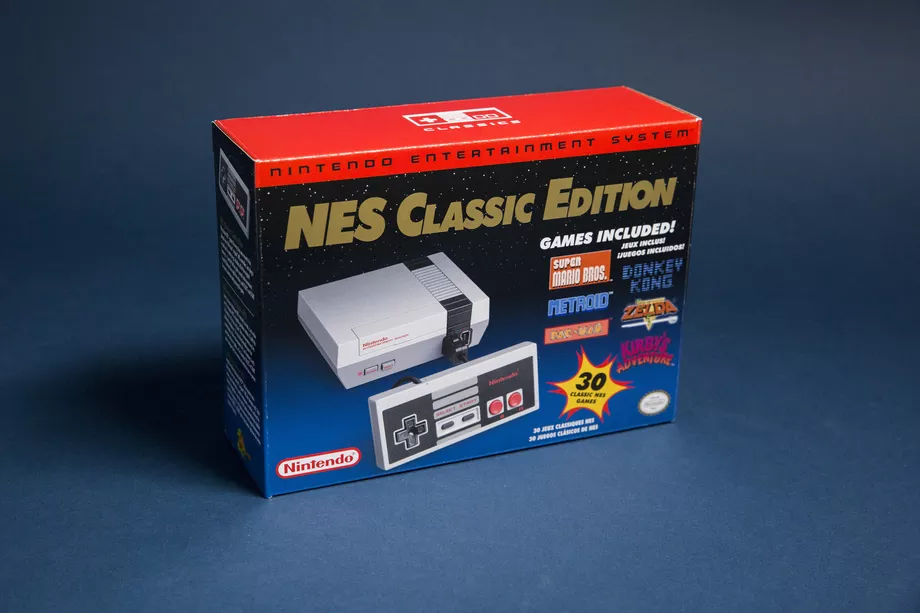

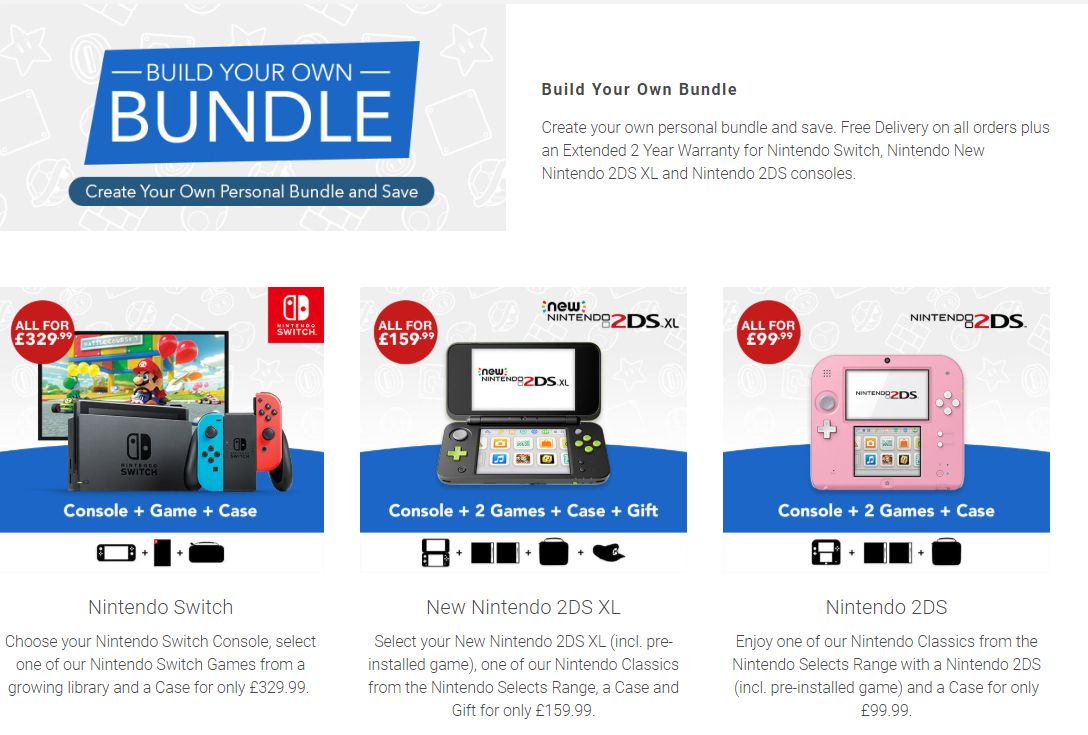

An extensive study of Nintendo sales of hardware (consoles) and software (games) showed the potential impact—and limitations—of bundling, especially bundle pricing, which may motivate consumers to enter a market more quickly or for the first time.

Timothy Derdenger and Vineet Kumar, who conducted the research, explain that bundling can be

especially effective in markets with intertemporal tradeoffs and significant consumer heterogeneity, e.g. durable goods like automobiles, consumer electronics and in technology markets where tradeoffs on when to purchase are especially important.

As Kumar continues in an interview with Forbes:

If consumers don’t like the offering you put out, they can postpone their purchases. In a sense, you’re competing with yourself over time, especially if you’re a monopolist.

Bundle pricing introduces urgency even if waiting might benefit the consumer (game console prices come down, technology advances).

Consumer choice, Kumar notes, remains critical. Even as mixed bundling increased sales for Nintendo, pure bundling reduced them by 20%. Preserving consumer choice—bundle or console, now or later—allows different market segments to choose different solutions.

For Nintendo, Kumar recommended taking the bundle a step further by allowing consumers to choose the game to bundle with their console and maximize the “positive synergy” between items. Nintendo appears to have listened:

For sellers, custom bundling is easier in the ecommerce era: Companies don’t need to pre-bundle, ship, or stock inventory at brick-and-mortar stores. Customization lets consumer preferences drive decisions on which products to bundle and, in turn, makes those bundles more relevant.

Using consumer expectations to your advantage

Bundles succeed more often when included items are usually purchased together. Similar items enjoy an inherent synergy: a hamburger, fries, and a Coke are components of a meal. Likewise, a bundled price for a loveseat and sofa makes sense—most living rooms have one of each, and consumers want them to match.

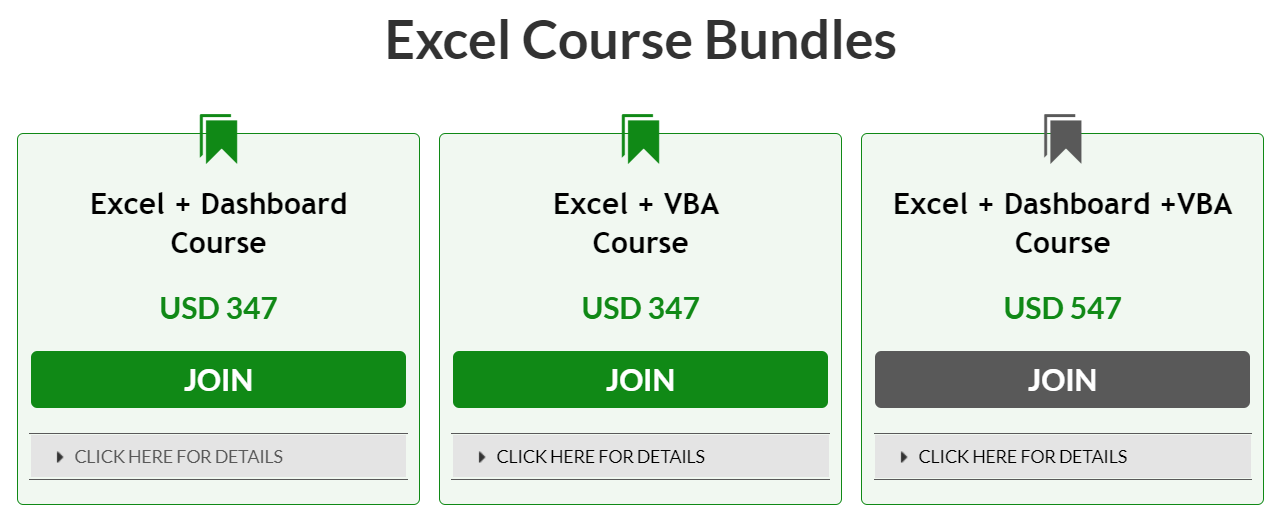

Sumit Bansal, who sells training courses on Microsoft Excel, experienced—for better and worse—the subtleties of those differences:

A bundle where I sell a basic and advanced Excel course is more appealing as the bundle promises to take care of everything on that specific topic. On the other hand, a bundle of two advanced courses on different courses didn’t work at all.

For Bansal, successfully bundling products hinged on understanding the business task that consumers needed to complete, not the user’s skill level.

For Bansal, successfully bundling products hinged on understanding the business task that consumers needed to complete, not the user’s skill level.

It’s the same concept behind bundles like our Digital Analytics minidegree—a package centered on start-to-finish mastery of a skill rather than a package of diverse skills targeting a certain level of practitioner.

Increasingly, recommendation engines enable companies to identify and promote products that consumers view as “similar.”

Recommendation engines: The new frontier in product bundling

It’s one thing for a salesperson to tell me that I should buy Monster cables (one of the great all-time rip-offs) with my new TV. It’s another for an algorithm to let me know what others purchased with their TVs.

A subtle but potentially critical tweak of copy by Amazon: Recommendations are what others “frequently bought,” not salesy prodding.

A subtle but potentially critical tweak of copy by Amazon: Recommendations are what others “frequently bought,” not salesy prodding.

Purchase data fuels the predictive algorithms that recommend product bundles. Those recommendations have two distinct benefits:

- They seem like insider knowledge from other buyers, making them welcome opportunities to reduce cognitive load. As McKinsey has found, peer recommendations have up to 10 times the influence of those from sales staff.

- They’re fully customizable mixed bundles that maximize consumer choice.

Conclusion

“There’s more potential to get it right than to get it wrong,” Kumar says of bundling. And yet, potential guarantees nothing.

A price-based focus on value is the greatest challenge for bundling strategies—the presenter’s paradox is in play, and categorical reasoning deflates the total value. Discounts may work well for a market segment (price-sensitive customers), but avoiding price comparisons entirely may succeed most often.

The diverse benefits of bundling to sellers—which extend well beyond near-term revenue—are a strong incentive to invest the time in strategy and testing to get it right. Even a simple price threshold for free shipping encourages consumers to build custom bundles and spend more, while also allowing ecommerce companies to carry low-cost items profitably.

For its part, technology is helping: Recommendation engines offer custom bundles at the point of sale that meet customer needs—and help companies hit revenue targets.

Business & Finance Articles on Business 2 Community

(187)

Report Post