— October 23, 2017

“Productivity vs efficiency; which do you think is more important?“

A colleague asked me this the other day and I had to catch myself, because my initial response was:

“Aren’t they the same thing?“

That’s the problem – the words have become so overused and confused that they are almost taken to mean the exact same thing in casual conversation. There are, however, key differences between the two that you should know in order to correctly analyze the performance of something.

Simply put, productivity measures output over time whereas efficiency measures input versus output. Together they can tell you how quickly something is completed, the resources it takes to get there, and (through analysis) whether the whole thing is worth your investment.

There are also dangers associated with these metrics. For example, I tried to spend an hour every night working on one of many projects. Monday was playing guitar, Tuesday was physical drawing, Wednesday game development, Thursday digital drawing, Friday playing piano, and the weekend dealer’s choice.

Not only did I give up within a week and a half, but I couldn’t muster the motivation to do any work on any of my projects for weeks following. It doesn’t matter if you’re using the best productivity apps around; when you’re using productivity and efficiency as your goal, rather than the method to reach it, something will inevitably break underneath you.

So, in this post I’ll go through:

- What productivity is

- The pros and cons of productivity as a metric

- What efficiency is

- The pros and cons of efficiency as a metric

- When to use each of them

- The problems and dangers of both

It’s time to analyze performance and improve your workflows without all the meaningless jargon. Let’s get started.

Productivity

“Productivity” means different things to different people

Before I dive into what I’ll be defining as “productivity”, it’s worth noting that the term is applied to a vast array of different circumstances, each with its own nuance in meaning.

First appearing in use in the early 19th century, “productivity” was originally a very focused around agriculture. Plots of land, types of soil, and varieties of plants were deemed more productive if they had greater product yield. This yield (productivity) could be judged over time to see where the best locations were for particular crops, along with aspects such as the effect of different soils and the yield of crops in general.

Modern standards instead talk about productivity almost exclusively in terms of people; specifically, they use it as a measure of the amount of work a person can do.

Thankfully there are some constants between all uses of the word; the idea of tracking the rate at which goals are met.

To most modern audiences, “productivity” means “the rate at which products are created or important work is completed”

The term “productivity” is banded around so much that it’s almost lost all meaning by now. Most seem to use it as a substitute for “volume of work”, but as I’ve already demonstrated, that shouldn’t be the case.

You can be busy without being productive since the amount of work you do isn’t necessarily linked to how worthwhile the tasks are. Five hours spent on minor admin and clearing your inbox is all well and good, but 2 spent working towards an imminent deadline are far better spent.

Even if we go back to agriculture, a greater yield over time doesn’t mean that said yield will be sell-able. Four tonnes of vegetables that are pasty and malnourished will be worth less than two or three of a high quality.

In other words, “productivity” should take into account both the amount of work completed and the worth of that work towards your end goals (even if that just means “increasing profits”).

It’s also vital to have a set amount of time to examine for the work being completed. After all, tracking performance without being able to draw conclusions from trends is next to useless.

By limiting your examination to a set time period you can analyze how well you’re performing, how that compares to your past efforts, and thus what elements might be affecting your output.

So, while the term is certainly overused (almost becoming jargon at this point), “productivity” does have a set meaning beyond “how well you’re doing”. It’s a specific measurement of the amount and value of the work that’s been completed in a set amount of time, such as weekly, monthly, or quarterly.

Productivity is great for measuring raw output and performance

Since “productivity” is a measure of output over time, it makes a fantastic way to judge the performance of, well, anything.

There’s no set consensus on when “productivity” isn’t appropriate to use as a measurement, but it admittedly makes more sense to apply it to people and processes than machinery. This is because the time spent to achieve a certain result is far more variable when looking at a process with human elements or a person’s performance.

I’m not saying you can’t use it to measure the performance of a machine, but it’s far less worthwhile than other methods (such as efficiency) since there’s often very little you can do to affect the time it will take. Aside from something breaking or a significant hardware upgrade there’s not going to be a significant shift in productivity, so it’s not as useful as a metric.

Basically, it’s good for making sure that machinery is working as expected, but not so much for predicting or pre-emptively solving problems that could affect its output.

When used to measure the performance of people and processes, however, productivity is incredibly useful, since minor tweaks in your workflow can result in massive shifts in the time taken to complete a task.

Not only that, but it can also help to indicate when a problem occurs, since you can compare the productivity of someone (or something) to their past performance. This, in turn, will allow you to help the subject in question recognize, diagnose, and deal with the problem much faster than you would otherwise be able to.

Unfortunately, productivity has its own weaknesses as a metric…

It falls flat when considering outside influences and mechanical elements

I’ve already mentioned how productivity is not nearly as useful when looking at things which are unlikely to change over time. Machines are a typical example of this – since they (usually) perform a set action at a consistent rate, measuring their performance over time isn’t very useful.

The other main area where productivity falls flat is in considering the resources invested in completing the work set out. It’s certainly true that time is an important thing to track, but in terms of physical resources (money, materials, and so on) there is no consideration at all.

This means that a person can be highly productive while also wasting far more resources than their peers. The work itself will get completed in less time, sure, but the relative profit from your resource investment could be lower.

Again, to return to the farming example, producing four tonnes of vegetables is better than producing three of the same quality. However, if the extra ton was a result of expensive fertilizers and insect repellents, you may well earn less profit than by selling the natural three tons.

Productivity’s worth as a metric also depends on how you use it. I’ll go into this more when comparing productivity to efficiency, but for now, know that while productivity can tell you the base performance over time, it can’t tell you the reason for this by itself, and can even be detrimental if focused too much.

Efficiency

Efficiency is output vs resource investment

While productivity deals in time, efficiency is all about resources – it’s a measure of the output generated from the resources put into a particular task (or set of tasks). The “resources” invested could be anything from money to components or time, and by measuring the amount put in compared to the amount of useful output you get in return, you get the efficiency of the whole task.

For example, the efficiency of a nuclear power station is 33-36%. This is because of the resources required to generate energy (and safely contain it) from nuclear sources, which are far greater than that of coal energy production. As a result, coal-powered energy stands at 39-47% efficiency.

In this sense, it’s understandable why many have struggled to separate it from productivity. Since time is a resource and efficiency is a measure of resources vs output, it can potentially cover the same ground.

However, there is a key difference. Productivity deals in the rate at which results are achieved, but efficiency focuses instead on the resources invested and the level of waste involved.

Let’s keep things consistent and stick with farming for our example. So, if two farmers both produced 4 tonnes of identical quality crops in the same amount of time, their productivity would be the same. However, one may have used more fertilizer or fuel than the other in the process, meaning his resource investment was greater for the same result.

Greater resources for no gain in results means that there’s a lower return on investment and (generally) more waste. Therefore, while their productivity was equal, their efficiency would show which was more successful.

It’s good for measuring relative profit and waste

Efficiency is great for telling you whether a particular effort is worth the resources it takes to achieve it. Not only that, but by comparing the efficiency of several elements in creating the same result, you can better judge which is the best choice to go with.

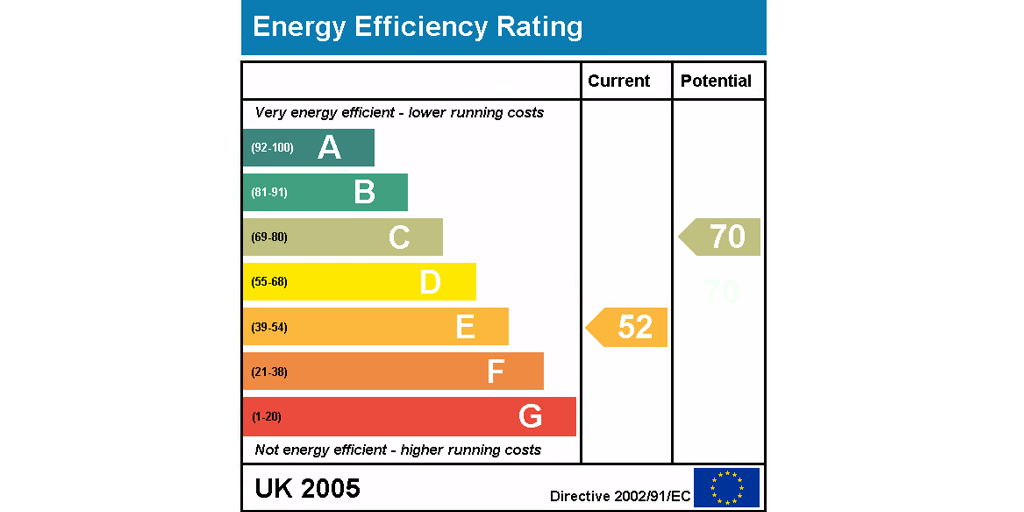

Due to the focus on resources invested and the waste involved in a task or process, efficiency is also more suitable for tracking the performance of machines and processes than people.

That’s not to say that you can’t track the efficiency of a person, but time is a key metric in measuring human performance, and so productivity is more commonly used. Things that don’t change much based on time, however, rely more on metrics like the resources used and wasted (hence why you have an “energy efficiency” rating for your home instead of a “productivity” rating).

The resources a person uses to achieve their results are still important to track, but the level of waste plays a far more significant role in the overall effectiveness of a machine or process.

Let’s say you wanted to assess which tractor to use when plowing the fields for a new crop. Tractor A gets the field done 10 minutes faster than tractor B, so in terms of productivity, A is the obvious choice.

However, by looking at their efficiency you notice that tractor A uses 35% more fuels than tractor B, effectively increasing your fuel spend by almost a third.

Whether that extra expense is worth the time saved is up to you, but the point is that efficiency highlights another side of the stone that you can consider when looking for ways to improve what you’re doing.

Efficiency doesn’t show the cause of problems or deal well with people

Efficiency, much like productivity, doesn’t highlight what any potential problems could be. Instead, it’s useful as an indication of how well a particular element is performing relative to previous results.

For example, a machine’s efficiency going down shows that there’s an issue which needs to be solved, but diagnosing that issue requires further analysis.

The metric also falls a little flat when considering elements and activities which are highly time-sensitive. If one machine is more efficient but another completes the task quicker, speed may be considered more important.

Finally, much like productivity, efficiency is less reliable as a performance metric when dealing with things that have highly variable characteristics.

Think of it this way; let’s say that your “performance” is a jigsaw made up of pieces like “efficiency”, “motivation”, “productivity”, and so on. The more pieces that are unknown or missing, the harder it is to figure out the final result.

Efficiency is most useful when it is the only inconsistent factor in your performance. Every other element which varies makes efficiency just one of a growing number of unknown elements (pieces to the puzzle), thus diminishing how important it is by itself.

That’s why it’s so good for measuring the performance of machines – most of the variables associated with them are more consistent than those which affect the output of a person (machines don’t require motivation). In a similar vein, the level of waste is directly tied to the overall worth of a process, and so efficiency is vital in highlighting where improvements are most needed.

Productivity vs efficiency: Which should you focus on?

Use productivity to measure personal performance

As I’ve already stated, tracking productivity is a great way to measure the performance of people and processes that heavily rely on human elements. However, it should only be used as a rough guide, rather than a justification for any major decisions (such as promotions or terminations).

Again, this is because productivity as a metric shows the performance of the thing being assessed over time, but doesn’t give any indication as to the reason behind any dips or gains.

For example, an employee’s productivity dropping could be a sign that they have personal circumstances affecting their performance. Alternatively, they could just be burnt out or struggling through a difficult project and need a little help on your end in order to push past the obstacle.

Productivity is also a great way to measure your own personal performance, since you can use it to see exactly what you’ve been doing and how long your tasks have taken. This knowledge (combined with the surrounding elements such as your work environment) will let you see what affects your performance and how you might be able to improve your consistency.

Use efficiency to measure process performance

Efficiency, meanwhile, is better used when looking at the performance of machines and processes. While it covers some of the same ground as productivity (if you’re tracking the time invested into a project), it’s ultimately most useful when being used to look at the level of waste involved in achieving a particular result.

In turn, this means that it’s most useful as a metric when the number of resources used (or wasted) while completing a task is easily adjusted, or more variable than other elements such as time.

For example, machinery will (in theory) be consistently productive. Since that’s the case, elements such as the amount of waste in its operation become much more important when assessing how useful it is and whether it’s worth the investment.

Processes are similarly good to use efficiency as a key metric of, since you’re then able to see where the greatest amount of waste is, and thus where the biggest savings can be made. Productivity is also less important (making efficiency more important) when addressing a process as a whole, since you’re assessing how long and how much it takes to complete the process, rather than how much can be completed in a set amount of time.

But take both with a pinch of salt

So, both productivity and efficiency have their place, and neither can be completely ignored in order to get the full picture of how something is performing. However, both have their shared weaknesses and dangers concerning their use.

For one thing, these metrics alone should not be used to justify important or radical decisions. I’ve already mentioned how outside elements can affect both productivity and efficiency, but the point is that any undesired results or sudden drops in either metric should be investigated further.

They are both indications of a problem, but neither explains the source without further investigation.

It’s also worth noting that the true solution to productivity vs efficiency can be “neither”.

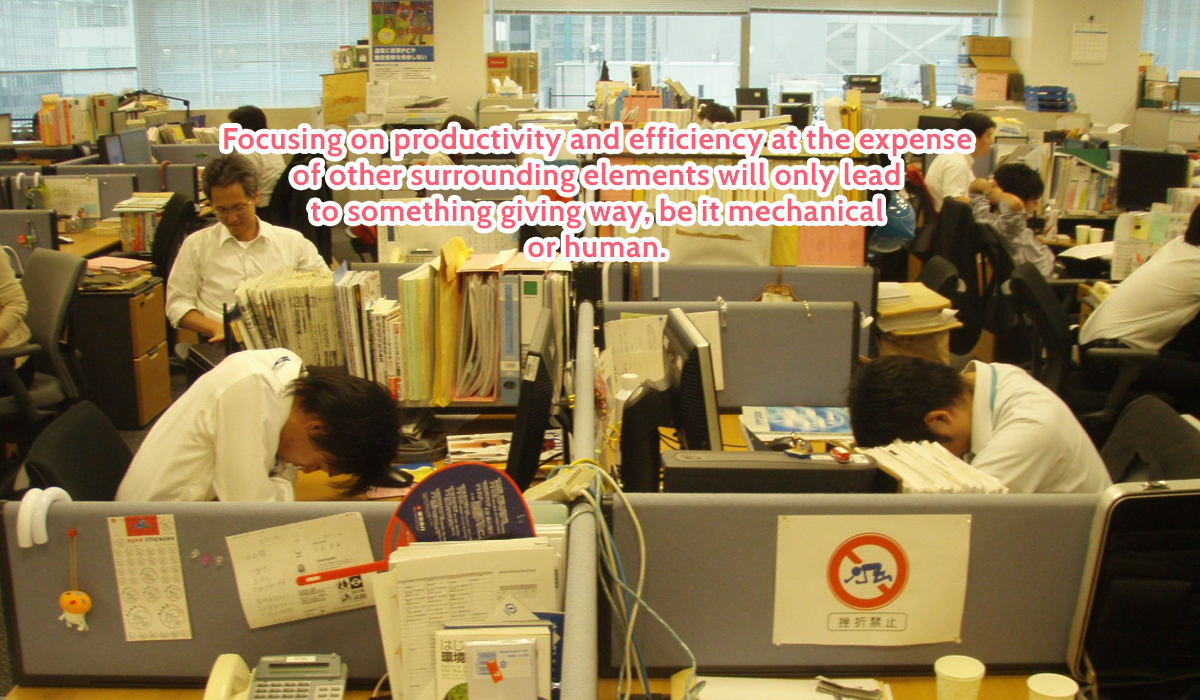

If you focus on productivity and efficiency alone without consideration for the things that they affect (such as the mental health of people involved in the assessed area) you can very quickly do more harm than good.

As I mentioned earlier, I wanted to start on the many projects floating around my head, so I decided to make a schedule. I wanted to practice physical and digital art, video game development, playing guitar and piano, writing for my personal blog, and a few other bits and bobs.

I reasoned that if I could do an hour of one of these each night, I’d soon make progress and see what I wanted to take further. I was wrong, and burned out rapidly.

By focusing on doing as much as possible on as many things in a set time period, I forgot to take both the scale and focus into account, and so doomed those projects before even starting them. Instead, I’m now doing one project at a time for an hour a week (at minimum).

It might take longer to work through everything I want to try, but as with any good process, consistency is more important than quick wins. Rather than give up after a week and a half of exhaustion and frustration, I’m instead going into my projects refreshed and allowing myself to actually relax during my downtime.

After all, to work smart you sometimes have to work a little less.

How do you think of productivity and efficiency? Are they overused and meaningless, focused on too much, or still incredibly useful in keeping track of your performance? Let me know in the comments below!

Business & Finance Articles on Business 2 Community

(173)

Report Post