— August 23, 2018

“I travel around the world constantly promoting my projects and endorsing products.” – Paris Hilton

Agile coaching is a journey into irony. One of the chief discoveries you can make on this voyage is that the more experienced you become, the worse at the job others often think you get.

For example, you might appear less sure about your ability to bring off projects “faster and cheaper”. This is rather awkward, given that such efficiencies are something which clients very often claim to want, and they can be singularly convinced of this matter. You, however, have begun to question the received wisdom upon which the project model is even based.

“Agile practice isn’t really about doing projects faster and cheaper”, you have come to learn, and now try to explain to others. “It’s more about building the right thing at the right time”. Economies can be expected to derive from the reduction of waste, but the operational running cost of a project is unlikely to be reduced in the short term. You warn that agile development could actually prove more expensive, at least to begin with, as any new practices will take time to bed in. Also, there is likely to be improved transparency over certain hidden costs, such as technical debt, which might presently be compounding unappreciated.

These are not always observations which others wish to hear. There is a strong market for sweet lies and simple answers, and by questioning core beliefs you can easily dig yourself into a hole which the less accomplished would – ironically – avoid. The path of least resistance is to adopt existing cultural values, including faith in a project model, and not to challenge such assumptions.

“In fact”, you say as you dig your own grave, “the very idea of having a project at all may need to be reconsidered. In an agile way-of-working we are more concerned about the delivery of products and services, the value of which is empirically proven by means of validated learning. We have less interest in the supposed efficiencies of temporary endeavors like projects, with their setup and teardown costs and other untracked forms of waste”.

Your listeners stare at you blankly.

“Why is it”, they say to themselves, “that we have junior staff – people with far less impressive backgrounds – who have no problem grasping the need to deliver projects faster and cheaper? Why can’t this muttonhead see it? Can’t he understand the organizational change which would be needed to attempt the realignment he’s suggesting?”

“This chap might have been good once,” they shake their heads despondently, “but he’s lost his mojo now!”

Then again, perhaps irony is just an unmapped circle of hell reserved for agile coaches. Of course you understand the organizational change which would be needed to replace a project model with products and services…and that’s exactly where you were trying to steer the conversation. However, it’s not a direction others wish to go. The upheaval that would be involved in realigning a project-based organization to value streams is far too daunting.

Unfortunately, the appetite for deep and pervasive enterprise transformation is rarely strong, and any sponsorship for real change is typically weak. This means it’s important to be sanguine when dealing with a project-oriented organization, its associated culture, and the frozen executive mentality which often accompanies it. You have to acknowledge the realpolitik of the situation…and that means learning to live with projects.

How to do this though? The Scrum Framework, which is appealed to so widely in agile practice, very clearly has a product focus and not a project one. There are no project managers in Scrum, and accountability for value is invested squarely in a Product Owner. The project management function, such as it is, is refactored and distributed across this role, the Scrum Master, and most especially the Development Team.

This can lead practitioners to assume that the very idea of a project is verboten in Scrum. However, a search for the string “project” in the Scrum Guide may prove instructive and worthwhile before any such conclusion is drawn.

We first encounter the term when Scrum Sprints are defined:

“Each Sprint may be considered a project with no more than a one-month horizon. Like projects, Sprints are used to accomplish something. Each Sprint has a goal of what is to be built, a design and flexible plan that will guide building it, the work, and the resultant product increment.”

Then, when describing Sprint Planning:

“The input to this meeting is the Product Backlog, the latest product Increment, projected capacity of the Development Team during the Sprint, and past performance of the Development Team.”

And concerning the Sprint Review:

“The Product Owner discusses the Product Backlog as it stands. He or she projects likely target and delivery dates based on progress to date (if needed)”

When evaluating progress towards a goal of some sort:

“At any point in time, the total work remaining to reach a goal can be summed. The Product Owner tracks this total work remaining at least every Sprint Review. The Product Owner compares this amount with work remaining at previous Sprint Reviews to assess progress toward completing projected work by the desired time for the goal. This information is made transparent to all stakeholders.

“Various projective practices upon trending have been used to forecast progress, like burn-downs, burn-ups, or cumulative flows.”

Finally, when specifically monitoring Sprint progress:

“At any point in time in a Sprint, the total work remaining in the Sprint Backlog can be summed. The Development Team tracks this total work remaining at least for every Daily Scrum to project the likelihood of achieving the Sprint Goal.”

The first two of these seven occurrences provide a clear endorsement of the idea of having a project, at least in theory. We can discern the usual understanding of a project as being a temporary endeavor planned to achieve a certain aim. Yet we also see a radical departure from convention in the assertion that a Sprint “project” cannot exceed one month in length. Most of the projects with which managers are familiar will be framed to last several months or even years.

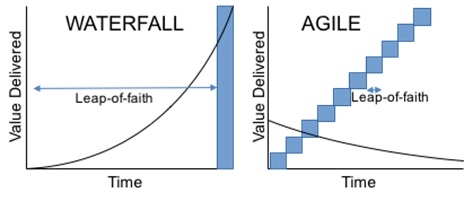

So short is this Scrum time-scale that it appears to make a nonsense of having a project at all. What, realistically, can be achieved in around two to four weeks? The fact that each increment is engineered to be a viable proposition takes us to the heart of why an agile way-of-working is different to that of a traditional “waterfall” stage-gated initiative. Each Sprint constrains the leap-of-faith required before value is obtained and empirical evidence of progress becomes available.

When a project lasts longer than a month, traditional means of tracking headway are resorted to, such as documents, reports, and sign-offs at notional stages of completion. The critical issue is that none of these artifacts release value. Rather they proxy for value which is expected to be released at some future point. They can amount to nothing more than promissory notes for a deficit which is being accrued and for the transfer of accumulated risk.

An agile “project”, in other words, is essentially predictable rather than predictive. It is predictable because empirical evidence of progress is made available in a timely manner, and hard data based on actual delivery outcomes can be used to inspect and adapt a wider plan, and to validate assumptions as well as any investment made. The leap-of-faith required to make any predictive claim may not exceed a one month time-span, but predictability can be leveraged to create reliable forecasts months or even years into the future.

Those longer-term forecasts can additionally be seen as projects of sorts, and indeed this is also a context in which the remaining occasions of “project” appear in the Scrum Guide. We find the words projected and projective being used such that a forecast might be made based on past performance and the rate of work which is actually completed.

This tells us the truth about projects in an agile way-of-working such as Scrum: they aren’t banished into the wilderness. It’s more the case that in a professional Scrum Team the word “project” will also be used considerately as a verb…and not assumed thoughtlessly to just be a noun.

Business & Finance Articles on Business 2 Community

(50)

Report Post