One of my favorite questions to ask during my keynotes is, “what’s management for?” It sounds like a simple rhetorical question, but I don’t ask it rhetorically. I let people discuss it and often ask what they concluded. (Try it now, before you read further. What’s management for? Why do we have it?)

The vast majority of answers understandably fall into a category I call managING. (In a keynote I call this, “managing with a capital ing,” because it’s tough to speak in all caps without sounding like you’re stressed out.) ManagING involves things like defining individual goals, setting and modeling policy, managing performance, supporting development, and dealing with compensation – to name a few. As soon as you get your first direct report, you’re managING, and you must take care not to minimize or ignore the function, especially as the size and level of your group increase. ManagING is how you make sure the work gets done.

Sometimes, people also answer in terms of change management. We share a substantive body of work around how to shepherd a group of people through a sizable shift, and that work is often done by managers. This is also natural and appropriate – after all, the word “management” is right there in the term, and making sure people tolerate and support change is a natural complement to making sure they get their work done.

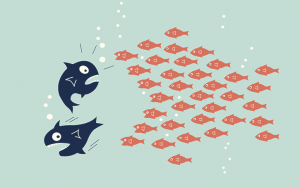

Neither answer is wrong, but both are incomplete. What’s so often missing from our shared definitions of management is what I call “management with a capital MENT.” That’s my term for a collection of managers working in collaboration with each other to coordinate competing work and ensure that the organization stays on track – that is, either on track to meet its highest priority goals, or on track to recognize the impossibility of those goals early enough to make non-disastrous changes to them. This is a decidedly different function from managING or change management. And while there’s nothing wrong with all of the making sure that those other functions entail, I’d argue that manageMENT is less about making sure and more about making decisions: decisions about what new information has surfaced and what it means to the plans as they stand today, decisions about whether some goals must be sacrificed or adjusted in favor of other, higher-priority ones, decisions about which resources, which projects, and which efforts need to be expanded or contracted to support the greater aims of the organization, and decisions about whether the cumulative result of all the work as currently planned will be sufficient to achieve the desired results – and if not, what’s to be done.

I’d also argue that the making of those decisions is often more important than all of the making sure that we ordinarily associate with management. No doubt, there’s room for both: once you know what you need your people to be doing, various forms of making sure they can do it, will do it, and are doing it all can be quite useful. But the minute something changes the utility of those plans – be it a change in the external environment, a change in the group’s understanding of the best way to proceed, or a change caused by the group’s own work – then all of that making sure the plans get implemented must take a back seat to deciding whether those plans need to change. Otherwise you’re chasing the wrong goals. And it is the managers, practicing manageMENT, who are uniquely positioned to recognize those changes and make those decisions.

I’ve spent the better part of my professional career researching and experimenting with proven approaches that get managers better at making those decisions: focusing on future expectations instead of past results, holding meetings that are structured but flexible, working together on higher level goals, and managing front line employees for maximum self-sufficiency. But lately I’ve come to appreciate that understanding those approaches might be the easy part. Implementation is more difficult, to be sure, and that’s where I spend the majority of my time with clients. But perhaps the most challenging aspect comes long before implementation, in the form of the assertion at the top of this post: to realize that the job of management isn’t just to make sure things happen, but to make decisions – often difficult ones – about what needs to be accomplished and how to get there. Doing this well isn’t possible without some challenging collaborations that go far beyond the superficial, touching on the competing agendas of the managers involved. This can be gnarly, quarrelsome, stressful work. But it’s also critical.

Why? Because if your organization is to avoid the bureaucracy of chasing after goals which no longer make sense, it’s going to have to adopt a level of agility that allows groups of managers to make substantive changes to goals and resource allocation at any time they’re needed. It can’t refer everything to the top for a ruling, and it can’t leave it to the workforce to sort things out informally behind the scenes. Your managers must be able to put aside their lower-level agendas and work together to make decisions about the best way to reach higher-level goals tomorrow. That’s what makes your management meetings functional rather than ceremonial. It’s what makes your company nimble rather than lumbering. And, it’s what makes the workdays of your managers turn out to be a whole lot less comfortable – and a whole lot more useful – than they would be if they spent all their time making sure. After all, you’re never really sure anyway, and as soon as you think you are, things change again. And that’s what management is for.

Business & Finance Articles on Business 2 Community

(80)