For a product that its own creators, in a marketing pique, once declared “too dangerous” to release to the general public, OpenAI’s ChatGPT is seemingly everywhere these days. The versatile automated text generation (ATG) system, which is capable of outputting copy that is nearly indistinguishable from a human writer’s work, is officially still in beta but has already been utilized in dozens of novel applications, some of which extend far beyond the roles ChatGPT was originally intended for — like that time it simulated an operational Linux shell or that other time when it passed the entrance exam to Wharton Business School.

The hype around ChatGPT is understandably high, with myriad startups looking to license the technology for everything from conversing with historical figures to talking to historical literature, from learning other languages to generating exercise routines and restaurant reviews.

But with these technical advancements come with a slew of opportunities for misuse and outright harm. And if our previous hamfisted attempts at handling the spread of deepfake video and audio technologies were any indication, we’re dangerously underprepared for the havoc that at-scale, automated disinformation production will wreak upon our society.

OpenAI’s billion dollar origin story

OpenAI has been busy since its founding in 2015 as a non-profit by Sam Altman, Peter Thiel, Reid Hoffman, Elon Musk and a host of other VC luminaries, who all collectively chipped in a cool billion dollars to get the organization up and running. The “altruistic” venture argues that AI “should be an extension of individual human wills and, in the spirit of liberty, as broadly and evenly distributed as possible.”

The following year, the company released its first public beta of the OpenAI Gym reinforcement learning platform. Musk resigned from the board in 2018, citing a potential conflict of interest with his ownership of Tesla. 2019 was especially eventful for OpenAI. That year, the company established a “capped” for-profit subsidiary (OpenAI LP) to the original non-profit (OpenAI Inc) organization, received an additional billion-dollar funding infusion from Microsoft and announced plans to begin licensing its products commercially.

In 2020, OpenAI officially launched GPT-3, a text generator able to “summarize legal documents, suggest answers to customer-service enquiries, propose computer code [and] run text-based role-playing games.” The company released its commercial API that year as well.

“I have to say I’m blown away,” startup founder Arram Sabeti wrote at the time, after interacting with the system. “It’s far more coherent than any AI language system I’ve ever tried. All you have to do is write a prompt and it’ll add text it thinks would plausibly follow. I’ve gotten it to write songs, stories, press releases, guitar tabs, interviews, essays, technical manuals. It’s hilarious and frightening. I feel like I’ve seen the future.”

2021 saw the release of DALL-E, a text-to-image generator; and the company made headlines again last year with the release of ChatGPT, a chat client based on GPT-3.5, the latest and current GPT iteration. In January 2023, Microsoft and OpenAI announced a deepening of their research cooperative with a multi-year, multi-billion-dollar ongoing investment.

“I think it does an excellent job at spitting out text that’s plausible,” Dr. Brandie Nonnecke, Director of the CITRIS Policy Lab and Associate Professor of Technology Policy Research at UC Berkeley, told Engadget. “It feels like somebody really wrote it. I’ve used it myself actually to kind of get over a writer’s block, to just think through how I flow in the argument that I’m trying to make, so I found it helpful.”

That said, Nonnecke cannot look past the system’s stubborn habit of producing false claims. “It will cite articles that don’t exist,” she added. “Right now, at this stage, it’s realistic but there’s still a long way to go.”

What is generative AI?

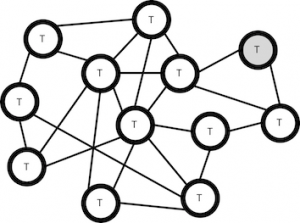

OpenAI is far from the only player in the ATG game. Generative AI (or, more succinctly, gen-AI) is the practice of using machine learning algorithms to produce novel content — whether that’s text, images, audio, or video — based on a training corpus of labeled example databases. It’s your standard unsupervised reinforcement learning regimen, the likes of which have trained Google’s AlphaGo, song and video recommendation engines across the internet, as well as vehicle driver assist systems. Of course while models like Stability AI’s Stable Diffusion or Google’s Imagen are trained to convert progressively higher resolution patterns of random dots into images, ATGs like ChatGPT remix text passages plucked from their training data to output suspiciously realistic, albeit frequently pedestrian, prose.

“They’re trained on a very large amount of input,” Dr. Peter Krapp, Professor of Film & Media Studies at the University of California, Irvine, told Engadget. “What results is more or less… an average of that input. It’s never going to impress us with being exceptional or particularly apt or beautiful or skilled. It’s always going to be kind of competent — to the extent that we all collectively are somewhat competent in using language to express ourselves.”

Generative AI is already big business. While flashy events like Stable Diffusion’s maker getting sued for scraping training data from Meta or ChatGPT managing to schmooze its way into medical school (yes, in addition to Wharton) grab headlines, Fortune 500 companies like NVIDIA, Facebook, Amazon Web Services, IBM and Google are all quietly leveraging gen-AI for their own business benefit. They’re using it in a host of applications, from improving search engine results and proposing computer code to writing marketing and advertising content.

The secret to ChatGPT’s success

Efforts to get machines to communicate with us as we do with other people, as Dr. Krapp notes, began in the 1960s and ‘70s with linguists being among the earliest adopters. “They realized that certain conversations can be modeled in such a way that they’re more or less self-contained,” he explained. “If I can have a conversation with, you know, a stereotypical average therapist, that means I can also program the computer to serve as the therapist.” Which is how Eliza became an NLP easter egg hidden in Emacs, the popular Linux text editor.

Today, we use the technological descendents of those early efforts to translate the menus at fancy restaurants for us, serve as digital assistants on our phones, and chat with us as customer service reps. The problem, however, is that to get an AI to perform any of these functions, it has to be specially trained to do that one specific thing. We’re still years away from functional general AIs but part of ChatGPT’s impressive capability stems from its ability to write middling poetry as easily as it can generate a fake set of Terms of Service for the Truth Social website in the voice of Donald Trump without the need for specialized training between the two.

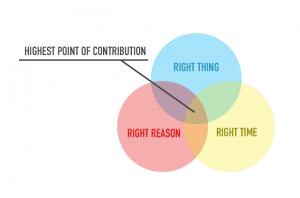

This prosaic flexibility is possible because, at its core, ChatGPT is a chatbot. It’s designed first and foremost to accurately mimic a human conversationalist, which it actually did on Reddit for a week in 2020 before being outed. It was trained using supervised learning methods wherein the human trainers initially fed the model both sides of a given conversation — both what the human user and AI agent were supposed to say. With the basics in it robomind, ChatGPT was then allowed to converse with humans with its responses being ranked after each session. Subjectively better responses scored higher in the model’s internal rewards system and were subsequently optimized for. This has resulted in an AI with a silver tongue but a “just sorta skimmed the Wiki before chiming in” aptitude of fact checking.

Part of ChatGPT’s boisterous success — having garnered a record 100 million monthly active users just two months after its launch — can certainly be marked up to solid marketing strategies such as the “too dangerous” neg of 2020, Natasha Allen, a partner at Foley & Lardner LLP, told Engadget. “I think the other part is just how easy it is to use it. You know, the average person can just plug in some words and there you go.”

“People who previously hadn’t been interested in AI, didn’t really care what it was,” are now beginning to take notice. Its ease of use is an asset, Allen argues, making ChatGPT “something that’s enticing and interesting to people who may not be into AI technologies.”

“It’s a very powerful tool,” she conceded. “I don’t think it’s perfect. I think that obviously there are some errors but… it’ll get you 70 to 80 percent of the way.”

Will Microsoft’s ChatGPT be Microsoft’s Taye for a new generation?

But a lot can go wrong in those last 20 to 30 percent, because ChatGPT doesn’t actually know what the words it’s remixing into new sentences mean, it just understands the statistical relationships between them. “The GPT-3 hype is way too much,” Sam Altman, OpenAI’s chief executive, warned in a July, 2020 tweet. “It’s impressive but it still has serious weaknesses and sometimes makes very silly mistakes.”

Those “silly” mistakes range from making nonsensical comparisons like “A pencil is heavier than a toaster” to the racist bigotry we’ve seen with past chatbots like Taye — well, really, all of them to date if we’re being honest. Some of ChatGPT’s replies have even encouraged self-harm in its users, raising a host of ethical quandaries (not limited to, should AI byline scientific research?) for both the company and field as a whole.

ChatGPT’s capability for misuse is immense. We’ve already seen it put to use generating spam marketing and functional malware and writing high school English essays. These are but petty nuisances compared to what may be in store once this technology becomes endemic .

“I’m worried because if we have deep fake video and voice, tying that with ChatGPT, where it can actually write something mimicking the style of how somebody speaks,” Nonnecke said. “Those two things combined together are just a powder keg for convincing disinformation.”

“I think it’s gasoline on the fire, because people write and speak in particular styles,” she continued. “And that can sometimes be the tell — if you see a deepfake and it just doesn’t sound right, the way that they’re talking about something. Now, GPT very much sounds like the individual, both how they would write and speak. I think it’s actually amplifying the harm.”

The current generation of celebrity impersonating chatbots aren’t what would be considered historically accurate (Henry Ford’s avatar isn’t antisemitic, for example) but future improvements could nearly erase the lines between reality and created content. “The first way it’s going to be used is very likely to commit fraud,“ Nonnecke said, noting that scammers have already leveraged voice cloning software to pose as a mark’s relative and swindle money from them.

“The biggest challenge is going to be how do we appropriately address it, because those deep fakes are out. You already have the confusion,” Nonnecke said. “Sometimes it’s referred to as the liars dividend: nobody knows if it’s true, then sort of everything’s a lie, and nothing can be trusted.”

ChatGPT goes to college

ChatGPT is raising hackles across academia as well. The text generator has notably passed the written portion of Wharton Business School’s entrance exam, along with all three parts of the US Medical Licensing exam. The response has been swift (as most panicked scramblings in response to new technologies tend to be) but widely varied. The New York City public school system took the traditional approach, ineffectually “banning” the app’s use by students, while educators like Dr. Ethan Mollick, associate professor at the University of Pennsylvania’s prestigious Wharton School, have embraced it in their lesson plans.

“This was a sudden change, right? There is a lot of good stuff that we are going to have to do differently, but I think we could solve the problems of how we teach people to write in a world with ChatGPT,” Mollick told NPR in January.

“The truth is, I probably couldn’t have stopped them even if I didn’t require it,” he added. Instead, Mollick has his students use ChatGPT as a prompt and idea generator for their essay assignments.

UCI’s Dr. Krapp has taken a similar approach. “I’m currently teaching a couple of classes where it was easy for me to say, ‘okay, here’s our writing assignment, let’s see what ChadGPT comes up with,’’ he explained. “I did the five different ways with different prompts or partial prompts, and then had the students work on, ‘how do we recognize that this is not written by a human and what could we learn from this?’.”

Is ChatGPT coming for your writing job?

At the start of the year, tech news site CNET was outed for having used an ATG of its own design to generate entire feature-length financial explainer articles — 75 in all since November 2022. The posts were supposedly “rigorously” fact checked by human editors to ensure their output was accurate, though cursory examinations uncovered rampant factual errors requiring CNET and its parent company, Red Ventures, to issue corrections and updates for more than half of the articles.

BuzzFeed’s chief, Jonah Peretti, upon seeing the disastrous fallout CNET was experiencing from this computer generated dalliance, immediately decided to stick his tongue in the outlet too, announcing that his publication plans to employ gen-AI to create low-stakes content like personality quizzes.

This news came mere weeks after BuzzFeed laid off a sizable portion of its editorial staff on account of “challenging market conditions.” The coincidence is hard to ignore, especially given the waves of layoffs currently rocking the tech and media sectors for that specific reason, even as the conglomerates themselves bathe in record revenue and earnings.

This is not the first time that new technology has displaced existing workers. NYT columnist Paul Krugman points to coal mining as an example. The industry saw massive workforce reductions throughout the 20th century, not because our use of coal decreased, but because mining technologies advanced enough that fewer humans were needed to do the same amount of work. The same effect is seen in the automotive industry with robots replacing people on assembly lines.

“It is difficult to predict exactly how AI will impact the demand for knowledge workers, as it will likely vary, depending on the industry and specific job tasks,” Krugman opined. “However, it is possible that in some cases, AI and automation may be able to perform certain knowledge-based tasks more efficiently than humans, potentially reducing the need for some knowledge workers.”

However, Dr. Krapp is not worried. “I see that some journalists have said, ‘I’m worried. My job has already been impacted by digital media and digital distribution. Now the type of writing that I do well, could be done by computer for cheap much more quickly,’” he said. “I don’t see that happening. I don’t think that’s the case. I think we still as humans, have a need — a desire — for recognizing in others what’s human about them.”

“[ChatGPT is] impressive. It’s fun to play with, [but] we’re still here,” he added, “We’re still reading, it’s still meant to be a human size interface for human consumption, for human enjoyment.”

Fear not for someone is sure to save us, probably

ChatGPT’s shared-reality shredding fangs will eventually be capped, Nonnecke is confident, whether by congress or the industry itself in response to public pressure. “I actually think that there’s bipartisan support for this, which is interesting in the AI space,” she told Engadget. “And in data privacy, data protection, we tend to have bipartisan support.”

She points to efforts in 2022 spearheaded by OpenAI Safety and Alignment researcher Scott Aaronson to develop a cryptographic watermark so that the end user could easily spot computer generated material, as one example of the industry’s attempts to self-regulate.

“Basically, whenever GPT generates some long text, we want there to be an otherwise unnoticeable secret signal in its choices of words, which you can use to prove later that, yes, this came from GPT,” Aaronson wrote on his blog. “We want it to be much harder to take a GPT output and pass it off as if it came from a human. This could be helpful for preventing academic plagiarism, obviously, but also, for example, mass generation of propaganda.”

The efficacy of such a safeguard remains to be seen. “It’s very much whack-a-mole, right now,” Nonnecke exclaimed. “It’s the company themselves making that [moderation] decision. There’s no transparency in how they’re deciding what types of prompts to block or not block, which is very concerning to me.”

“Somebody’s going to use this to do terrible things,” she said.

(10)

Report Post