— March 8, 2019

TL;DR: Technical Debt & Scrum

If technical debt is the plague of our industry, why isn’t the Scrum Guide addressing the question of who is responsibly dealing with it? To make things worse, if the Product Owner’s responsibility is to maximize the value customers derive from the Development Team’s work, and the Development Team’s responsibility is to deliver a product Increment (at least) at the end of the sprint adhering to the definition of “Done,” aren’t those two responsibilities possibly causing a conflict of interest?

This post analyzes the situation by going back to first principles, as laid out in the Scrum Guide to answer a simple question: Who is responsible for keeping technical debt at bay in a Scrum Team?

What Is Technical Debt?

According to Wikipedia,

“Technical debt (also known as design debt or code debt) is a concept in software development that reflects the implied cost of additional rework caused by choosing an easy solution now instead of using a better approach that would take longer.”

The issue is that there is not just the typical hack, the technical shortcut that is beneficial today, but expensive tomorrow that creates technical debt. (A not uncommon tactic in feature factories.)

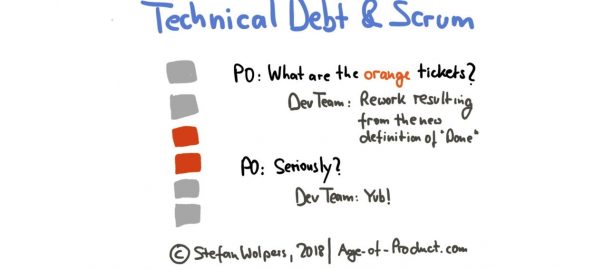

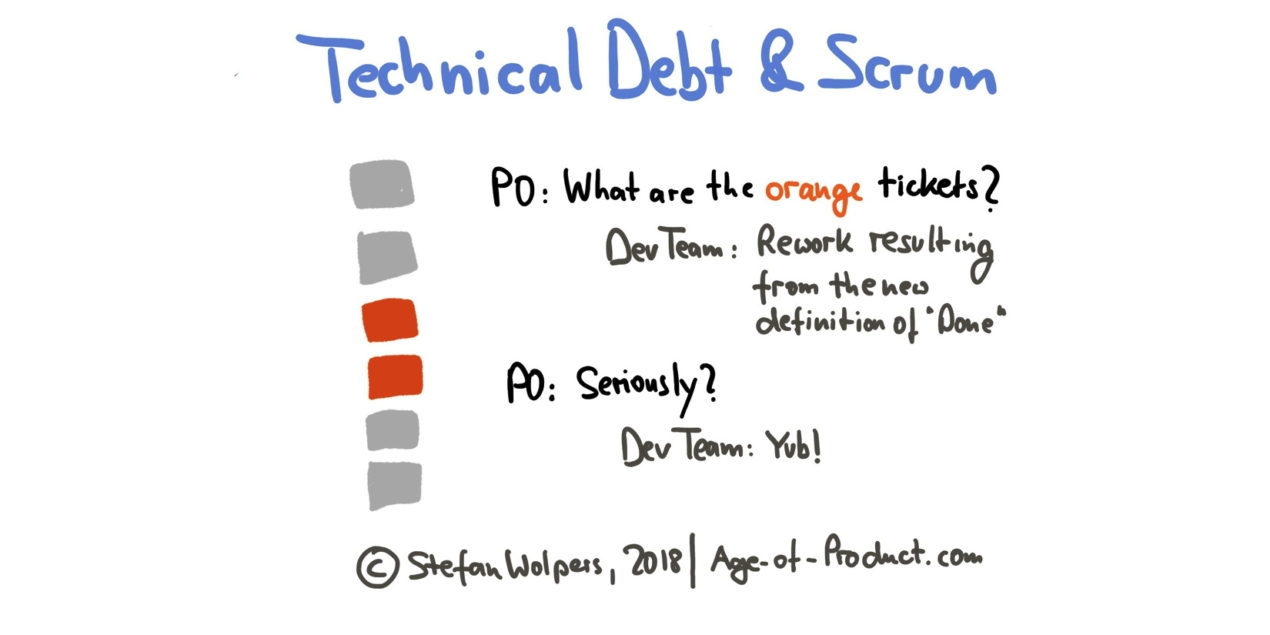

There is also a kind of technical debt that is passively created when the Scrum Team learns more about the problem it is trying to solve. Today, the Development Team might prefer a different solution by comparison to the one the team implemented just six months ago. Or, the Development Team upgrades the definition of “Done,” thus introducing rework in former product Increments.

No matter from what angle you look at the problem, you cannot escape it, and Scrum does not offer a silver bullet either.

Technical Debt & Scrum — The Scrum Guide

First of all, the Scrum Guide does not mention technical debt.

According to the Scrum Guide:

- The Product Owner is responsible for the maximizing of the value of the work of the Development Team.

- Product Owners do so by managing the Product Backlog, visible in its content and ordering of Product Backlog items.

- The Product Backlog represents the only set of requirements the Development Team will work on and shall comprise of everything the product requires to be valuable.

- The Scrum Team never compromises on quality.

- The definition of “Done” is either provided by the engineering organization or the Development Team.

- During the Sprint Planning, the Product Owner discusses Product Backlog items suitable to achieve the Sprint Goal.

- However, only the Development Team picks the Product Backlog items it deems necessary to achieve the Sprint Goal.

- If necessary, the Development Team adds new Product Backlog items to the Sprint Backlog as more is learned.

- If the Development Team improves the definition of “Done,” rework of former product Increments may become necessary.

Therefore, I believe the Scrum Guide is deliberately vague on the question who is responsible for the technical debt to foster collaboration and self-organization, starting with the Scrum values–courage, and openness come to mind—leading straight to transparency and Scrum’s inherent system of checks & balances.

How to Deal with Technical Debt as a Scrum Team

I am convinced that dealing with technical debt should be a concern of the whole Scrum Team. There are a few proven techniques that will make this task more manageable:

- Be transparent about technical debt. Visualize existing technical debt prominently so that everyone is constantly reminded of the nature of your code-base. Also, address technical debt at the Sprint Review events regularly so that the stakeholders are aware of the state of the application.

- Use code metrics to track technical debt, for example, cyclomatic complexity, code coverage, SQALE-rating, rule violations. (There are numerous tools available for that purpose.) At least, count the number of bugs.

- Pay down technical debt regularly every single sprint. Consider allocating 15 to 20 percent of the Development Team’s capacity each Sprint to handle refactoring and bug fixing. (Learn more: Scrum: 19 Sprint Planning Anti-Patterns.)

- Make sure that all tasks related to deal with technical debt are part of the Product Backlog—there is no shadow accounting in Scrum.

- Adapt your definition of “Done” to meet your understanding of product quality, for example, by defining code quality requirements that contribute to keeping technical debt at a manageable level in the long run.

- Create a standard procedure on how to handle experiments that temporarily will introduce technical debt to speed up the learning in a critical field.

In my experience, dealing with technical debt becomes much simpler when you consider transparency to be the linchpin of any useful strategy.

Technical Debt & Scrum — Conclusion

Given that solving a problem in a complex environment always creates new insights and learnings along the way that will make past decisions look ill-informed, creating technical debt is inevitable.

Handling technical debt, therefore, requires a trade-off. The longterm goal of achieving business agility cannot be reached as a feature factory churning out new features. At the same time, an application in a perfect technical condition without customers is of no value either.

Consequently, dealing with technical debt in Scrum is a responsibility for the Scrum Team as a whole and as such an excellent example of Scrum’s built-in checks & balances.

How are you handling technical debt in your daily work? Please share with us in the comments.

Business & Finance Articles on Business 2 Community

(120)

Report Post