When I was raising capital for Jopwell, my first startup, I remember going in to meet with a notable investor at a very well-known firm. I was nervous—so was my cofounder Ryan Williams. And when we walked into the board room our stomachs dropped again.

We immediately noticed that we were the only two people of color in the room. Given that we were pitching an HR technology solution to help advance the corporate careers of Black, Latinx, and Native American professionals, our concern was that they wouldn’t understand the unique obstacles our communities faced.

As we opened the pitch and began talking about the importance of diversity in recruiting, Ryan and I were met with increasingly vacant stares. It was clear they weren’t connecting with our story. They had a much less inherent understanding (or empathy) for the experiences and systemic problems we mentioned, as expected.

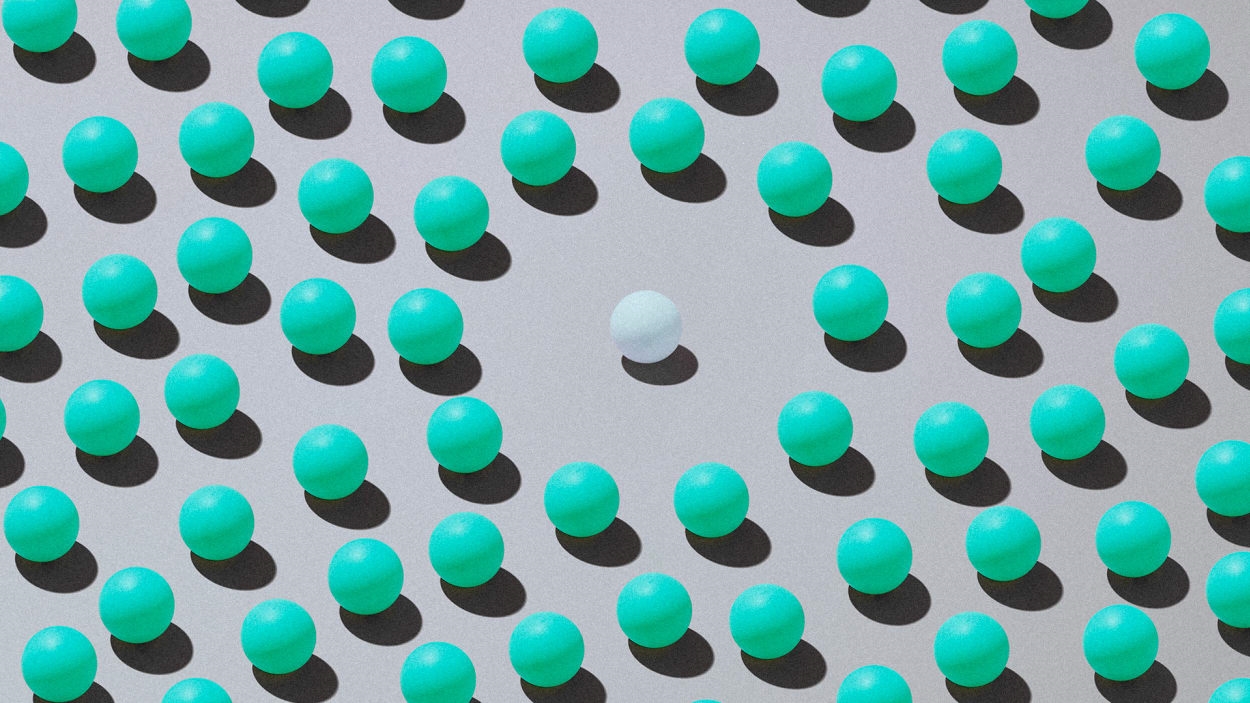

This situation must be deeply familiar to anyone who has ever felt like the odd one out in a professional, school, or other institutional setting. We call it being “the only.” It often happens that people from underrepresented backgrounds or communities—women, people of color, and people with diverse gender or sexual identities—find themselves being the only person “like them” in the company, meeting, conference, or other professional/public setting.

For women, this has long been an issue at the senior and executive level. Although things have changed in the past decade, the distribution of gender equality at the leadership level remains uneven. According to one recent study of over 1,000 companies in 54 countries, 77% of executives worldwide and 71% of senior managers are men. From a racial perspective, at least in the United States, the numbers are even less encouraging: 85% of US-based executives and 83% of senior managers are white, according to the same survey.

Being “the only” at different career stages

These numbers probably won’t surprise most of us. I’ve found that as my career has progressed and I’ve reached more milestones of success, I’ve felt the sensation of being “the only” more, not less. And while I’ve learned to deal with it over time, and even use it to my advantage in some situations, it’s important that we name and have empathy for this experience.

When you’re young and earlier on in your career, the feelings of alienation that being “the only” produces can really slow you down. I remember feeling nervous in my first job to speak up in meetings, because knowing that you’re different in an otherwise homogeneous setting automatically points a spotlight on you. You don’t know what expectations people will have of you and you fear that your behavior or words might receive undue attention or skepticism.

I recently spoke with Devika Bulchandani, Global CEO of Ogilvy, about her experience frequently being the only woman of color in a room. She remembers having “to muster all [her] courage” just to make contributions in the room. And that’s not hyperbole—can you imagine how much of an obstacle that must have been to a woman of obviously exceptional talent and drive early on in her career? “All” her courage? That’s not what a workplace should feel like if it’s truly enabling and empowering its employees.

But Bulchandani also told me that as time went on, she learned to use her identity and experience as “the only” with greater agency.

Transforming “the only” into “the expert”

One of the other feelings that being the “only” can suggest in a room is tokenism. It’s easy to suspect in some industries and situations that you’ve been brought into a room simply to beef up the “diversity quota”.

The advertising industry is no exception. Bulchandani mentioned to me that she’d once been invited onto a pitch, and after a few initial meetings, realized that she was not being fully utilized. She marched up to the account lead one day who was in charge and asked her straight up if she was on the pitch to actually contribute or because she was a woman.

To me, the boldness of the question shows just how far people of color have to go in professional settings. But according to Bulchandani, it worked. The account lead was sufficiently shocked out of their thoughtless inclusion of Bulchandani and her talent. Things changed, Bulchandani got to work with the team, and they won the pitch.

I love this story because it conforms to my own experience back in that boardroom when I was raising money for Jopwell. Realizing that our audience wasn’t really getting our story, we decided to pivot and use our position as “the only” to our advantage.

“Not one of you in this room can understand the story we’re trying to tell,” we boldly told them. Instead of begging them to understand us, we told them straight up: you can’t. There’s no way that you can understand the trials and pitfalls of Black, Latinx, and Native American students trying to get hired, because your background blinds you to it.

Rather than simply remaining representatives of “the only,” we transformed ourselves into their expert voice. We knew that our credibility and experience in this space vastly outstripped our audience. We told them as much, and it immediately reversed the power dynamic in the room. They realized they couldn’t afford not to listen to us because of this knowledge and experience gap. Being “the only” became a crucial advantage in our positioning, our credibility, and the salience of our proposed solution. (And yes – we did get the capital!)

Now that I’m older, I find it easier to wield my agency and power as “the only” in a room. My wife continues to point it out to me when we’re at social or work functions, but it barely registers for me anymore. It’s a daily part of my work and regular life, as it is for so many of us, and letting it get to me would prevent me from functioning at this point.

But I’m writing about it today because I hope we can all develop more empathy for that person who feels like “the only” in a room. And if you’re a person of color or someone who frequently feels that feeling, I want to tell you that it gets easier.

One of the most pernicious and overlooked deterrents to a harmonious workplace is a lack of belonging. When people feel like they don’t belong, they don’t share the full depth and range of their abilities. Some may even leave. It can be incredibly toxic to individuals and to a workplace overall to let a non-inclusive, dominant culture develop.

The infamous “impostor syndrome” sets into us all naturally at some point in our careers. But imagine how much stronger its hold must be, when you walk into an environment that visually and immediately suggests: you may not belong here.

It can take so many forms. Starting a new job and realizing that the culture is a complete “boys’ club,” dominated by male-male relationships, language, and codes of behavior. Going to an interview and seeing no people who look like you at the office or on the hiring team. Joining a board of heavy-hitting decision makers and realizing none of them can truly understand your background. These situations make it so much harder to bring out the best in people – both those who feel like “the only” and those who surround them. Homogeneity rarely breeds impressive results at work.

The real solution to being “the only”

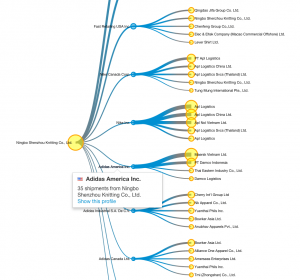

Of course, one of the most important antidotes in professional environments where people can feel like “the only” is to hire more diverse leadership. Seeing yourself reflected at higher levels in the company, even if you don’t work directly for or with those people, can radically alter people’s expectations and perceptions of a work culture.

Bulchandani told me during our conversations that already within her short time as the new CEO at Ogilvy, women had come up to her at work to share how important and encouraging it was to see her in that position. One woman said it made her feel proud to work at Ogilvy; another told her her parents back home were proud of her for working at the company. When people of color are in these senior positions it can transform individual careers and company culture.

Personally, I know it can be a lonely road for people of color, especially on the entrepreneurship track, where the numbers are even worse than in corporate America. While I’ve gotten used to the isolation, it nevertheless concerns me that it’s still there after all these years.

Things have definitely changed in the past 20-odd years. For one, racial differences are becoming less stark. The racial composition of America has changed, especially as the multiracial population grows. And we know we’re on track to be living in a country where racial and ethnic “minorities” will overtake the white “majority” population-wise in less than 20 years.

So maybe, one day, feeling like “the only” within certain communities will become a thing of the past.

But in the meantime, it’s important that we recognize and have empathy for this experience. It can severely limit the performance and sense of belonging that diverse talent feels at work. While many of us learn to wield our difference with greater intention and agency, every workplace should be trying to stem the need to do so.

Only 25% of companies in another recent survey say they prioritize hiring diverse leadership as part of their DEI strategy—even though 65% say they prioritize diversity throughout the entire company. That is one of the most immediate and important levers to use to implement change. Diverse leadership is directly correlated to improving employee experience and company culture, particularly—but not exclusively—for employees from diverse backgrounds.

The bottom line is: if you feel like “the only” or if you notice you work in a place where people might feel that way, your workplace and your team will have blind spots. Feeling like “the only” is a difficult experience personally, but it’s also a symptom of an organization veering into homogeneous and dominant cultures that demand assimilation.

This article was adapted and reprinted with permission from Diversity Explained.

(22)