By Kim Kelly

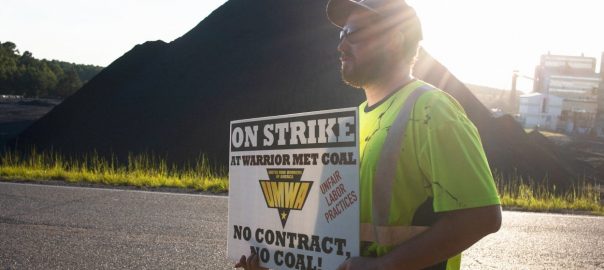

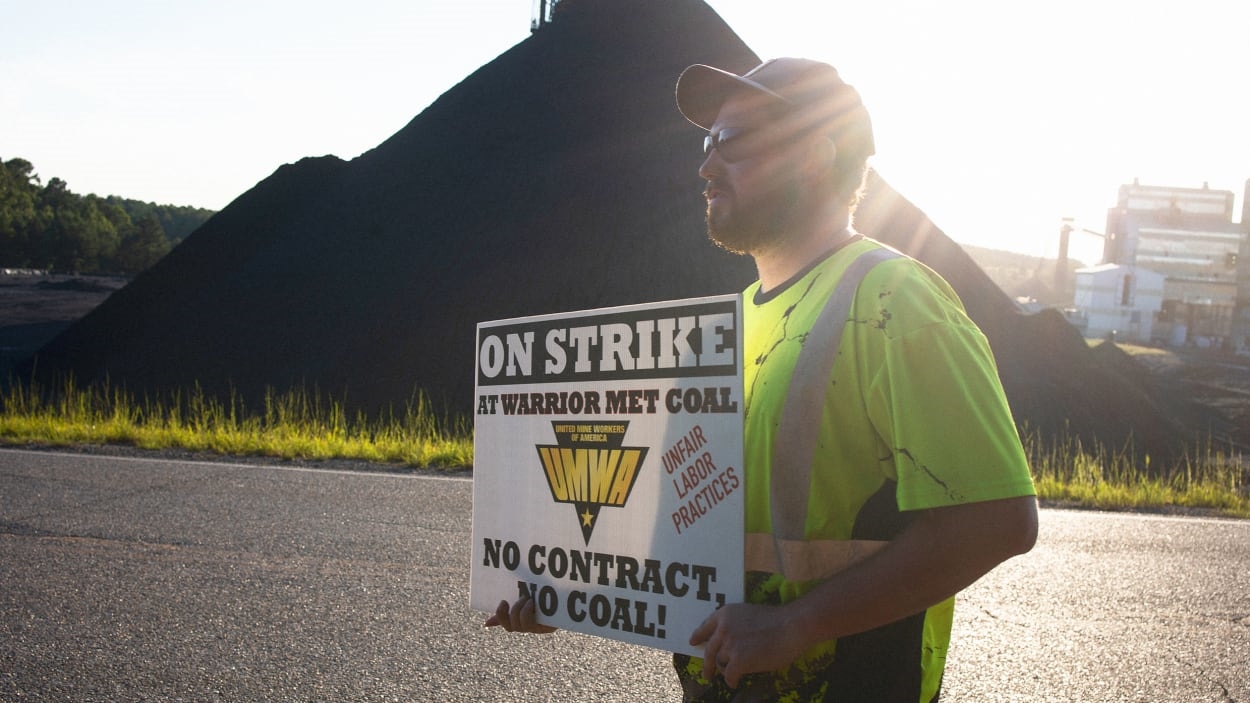

On February 16, the longest-running strike in the country came to an unexpected end when the United Mine Workers of America sent a letter to the CEO of Alabama-based Warrior Met Coal offering to send its members back to work.

Nearly two years ago, on April 1, 2021, more than 1,100 UMWA coal miners at the company’s four underground mines walked out, launching an unfair labor practices strike. The company, backed by Wall Street investment firms like BlackRock, had purchased the mines in 2016 following the bankruptcy of its former owners, Walter Energy. In convincing the miners to take a pay cut and accept a contract with terms below the industry standard to help the mine get back on its feet financially, Warrior Met promised to make up for those concessions in the next contract.

That never happened. After an initial round of contract negotiations to restore the concessions broke down, the union accused Warrior Met of bargaining in bad faith—the unfair labor practice that launched the strike. The walkout prompted an initial burst of movement at the bargaining table. The company and the union reached a tentative agreement, but the members voted overwhelmingly to reject it and stay out on strike.

Warrior Met Coal typically employs 1,300 workers, and is Alabama’s largest producer of metallurgical coal, which is used in steel production. BlackRock is the company’s largest investor, with a 13% stake (last year, the investment firm called on Warrior Met to settle the strike to no avail). Warrior Met’s latest earnings report showed that even with the strike holding firm, the company still brought in more than $640 million in net income. Meanwhile, under their last contract, some workers were making $22 per hour while working 12 hour days, six days a week.

I’ve been covering this story since the beginning, when I showed up to the picket line on April 10, 2021, and started asking questions, and have been back to Alabama to follow developments many times since. I’ve gotten to know the miners and their families well, and I’ve seen how much of a toll this fight has taken on them and their community. As the strike’s record-breaking duration might imply, it hasn’t been an easy fight, and often turned ugly.

After the workers walked out in April 2021, Warrior Met immediately brought in hundreds of replacement workers—scabs—from across Appalachia to keep running coal while the union members picketed outside. The company placed billboards as far afield as Kentucky and West Virginia, promising high-paying mining jobs to entice nonunion job seekers.

For union members (and those who care about the labor movement) a picket line is a sacred thing, and to purposefully cross over it is an inexcusable act. Crossing a picket line during an active strike shows that you don’t care about your fellow workers and are willing to weaken their strike and side with the bosses for your own benefit. As socialist writer Jack London once asserted, “A Strikebreaker is a traitor to himself, a traitor to his God, a traitor to his country, a traitor to his family and a traitor to his class.”

Violence on the picket line is not exactly a novel concept to coal miners, especially those who lived through the rowdy 1989 Pittston strike in southwest Virginia, and at the Warrior Met picket line there were multiple cases in which nonunion workers were caught hitting strikers with their vehicles as they drove to the mine. At one point, a nonunion worker drove his pickup truck into a barrel with a fire the picketers were using to keep warm and sent it flying into a miner’s wife, leaving her injured. In spite of the video evidence, the company instead tried to smear the miners as violent, unruly thugs, and hired a Los Angeles-based PR firm to nudge the local press into running articles about Warrior Met’s “safety concerns.”

Warrior Met used those altercations as a way to convince local judges to issue a series of injunctions and restraining orders aimed at keeping picketing miners off company property, eventually whittling down the picket line to nothing. The miners chafed against the legal restrictions and struggled to keep their spirits up as the months stretched on. Morale dipped as bills piled up, and by the strike’s end nearly 200 union members had either crossed the picket line or left to take other jobs, some in other local UMWA-represented mines.

But the overwhelming majority of the strikers held firm. It took a truly incredible amount of energy, dedication, and solidarity to sustain the strike for this long, and it’s a testament to the strength of the labor movement that so many people did show up for the miners, from union members from around the country to labor leaders like AFA-CWA President Sara Nelson; Grammy-winning musician and activist Tom Morello, who played a support rally; and actress Susan Sarandon, who showed up at one of the miners’ rallies in New York City planned to call attention to BlackRock’s complicity in the strike.

The most credit, however, should go directly to the women of the UMWA Auxiliary, who spent countless hours organizing events, cooking at rallies, collecting donations, speaking to the media, and running a strike pantry that fed more than 200 families each week, on top of working their own jobs and caring for their own families. They were the glue that held the strike together, building on a long coal-country tradition and inspired by labor organizer Mary “Mother Jones” Harris. For them, it was personal.

“When a man works for Warrior Met, the family works for Warrior Met,” Haeden Wright, the Auxiliary’s president and a striking miner’s wife, told me in our first interview back in July 2021. “Your entire family signs that contract . . . and women can be a whole lot more vicious when you attack our families.”

But the deck was stacked against them: One of the primary reasons that Warrior Met has been able to function for this long with a smaller, less-experienced temporary workforce is that coal prices are high enough to make up the difference. Because the company did not shut down when the COVID-19 pandemic hit and required its workers to continue running coal, Warrior Met also began the strike with a 2.8 million-ton stockpile that was ready to sell when the miners walked out. Add in anti-union Alabama politicians, law enforcement, judges, and labor laws, plus a profound lack of media attention and utter radio silence from the national Democratic political establishment, as neither President Joe Biden nor then-Labor Secretary Marty Walsh saw fit to mention them or offer meaningful support.

One would think that in our current moment of pro-labor sentiment, worker wins, and nationwide organizing campaigns, the strike would have warranted some prime-time news coverage or headlines in major national publications, but the miners have had a rough time getting their story out there, and they’ve lost out on the kind of public support that’s helped so many other recent strikes reach the finish line.

As the strike’s second anniversary loomed, the UMWA made the difficult decision to change its tactics—and prepare to send its members back to work. “We are entering a new phase of our efforts to win our members and their families the fair and decent contract they need and deserve,” President Cecil Roberts said in a letter to Warrior Met. “We have been locked into this struggle for 23 months now, and nothing has materially changed.”

Warrior Met accepted the UMWA’s offer, and the return date is currently set for March 2. The union’s plan is to continue bargaining for a new contract while the workers return to their jobs; for now, they’ll be covered by the former contract, which is not ideal but will at least ensure they can count on its basic protections.

What happens next is anyone’s guess; many workers have found other work outside the mines, and some are unsure whether they want to return to Warrior Met at all. The potential for further conflict or retaliation is high, and there’s also the matter of the hundreds of scabs still employed by the mine. There’s no telling how negotiations will go once the workers are back—but the miners have already earned their place in history.

(11)

Report Post