INSURRECTION.

That is the title of the first chapter in Edel Rodriguez’s graphic memoir, Worm. Rodriquez, an artist whose work has appeared on the covers of Time, The New Yorker, and many other publications, has established himself as the leading visual chronicler of the Trump era. Given the fact that Trump is now ubiquitous with the word, you might think you know what will follow on the next page.

But you’d be wrong.

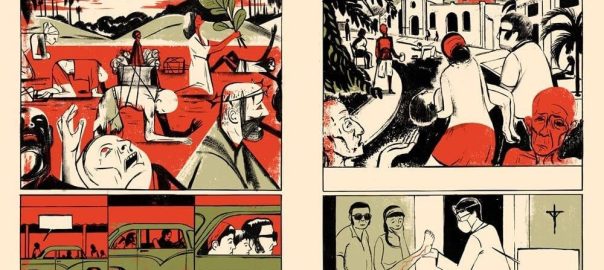

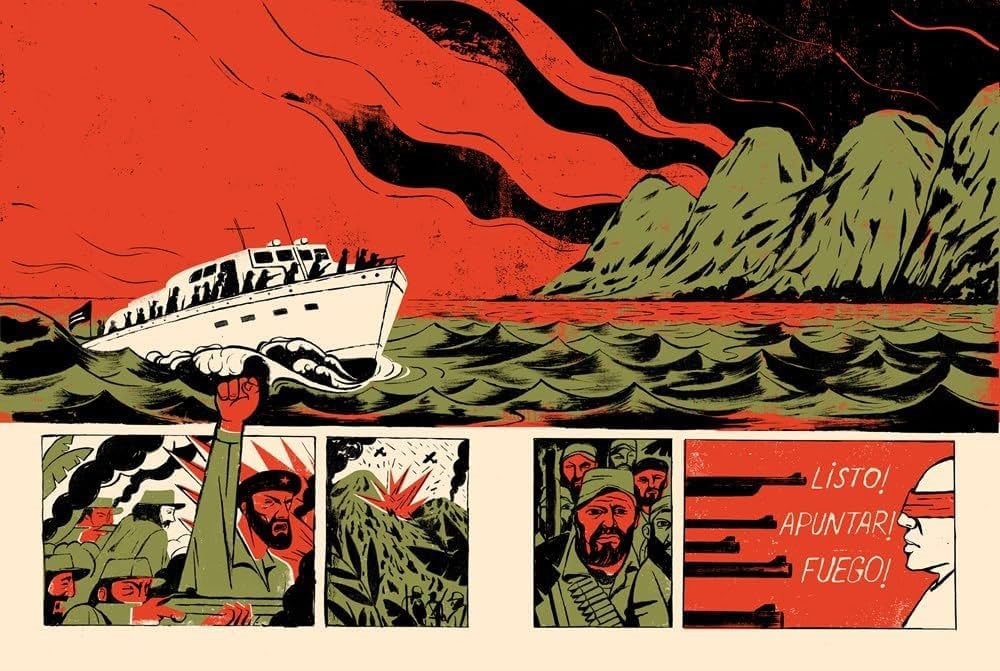

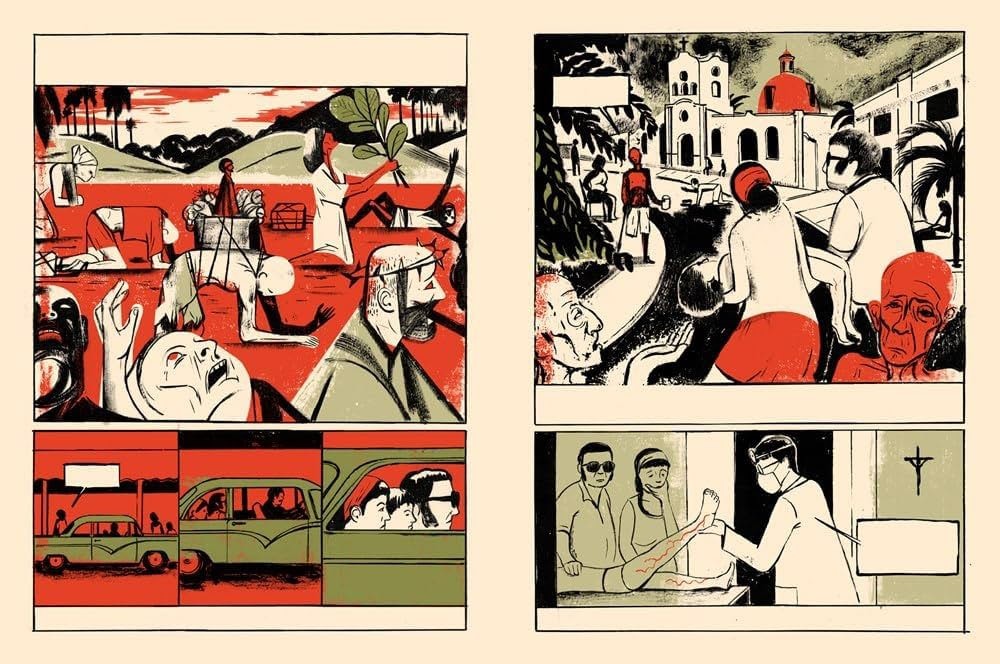

Instead of Trump, the page displays a “ragtag army of bearded young men” descending upon a capital in January.

It’s a brilliant start to Rodriguez’s memoir—a book that’s equal parts life story, historical document, and pressing warning.

A decade in the making, Rodriguez says he started Worm to capture his family’s journey from post-Revolution Cuba to America during the Mariel boatlift. But then 2016 rolled around. He had begun doing some of his soon-to-be-famous Trump illustrations, and a parent came up to him at one of his daughter’s school functions and murmured that she liked what he was up to. He asked why she was whispering. She said she didn’t know if any of the teachers were Trump supporters—and she didn’t want her comments to impact her child. Rodriguez was throttled, as it vividly reminded him of such pervasive fears in Cuba when he was growing up.

“At the same time, Trump was using the language that the press is the enemy of the people, which is exactly the thing that Castro had said, and Castro banned the press in Cuba. So all of these things came together, and I just kind of freaked out and figured I had to get very loud about this—so that if I were loud, other people would be loud, too.”

At that point, his political work grew in scope, and the memoir grew in complexity.

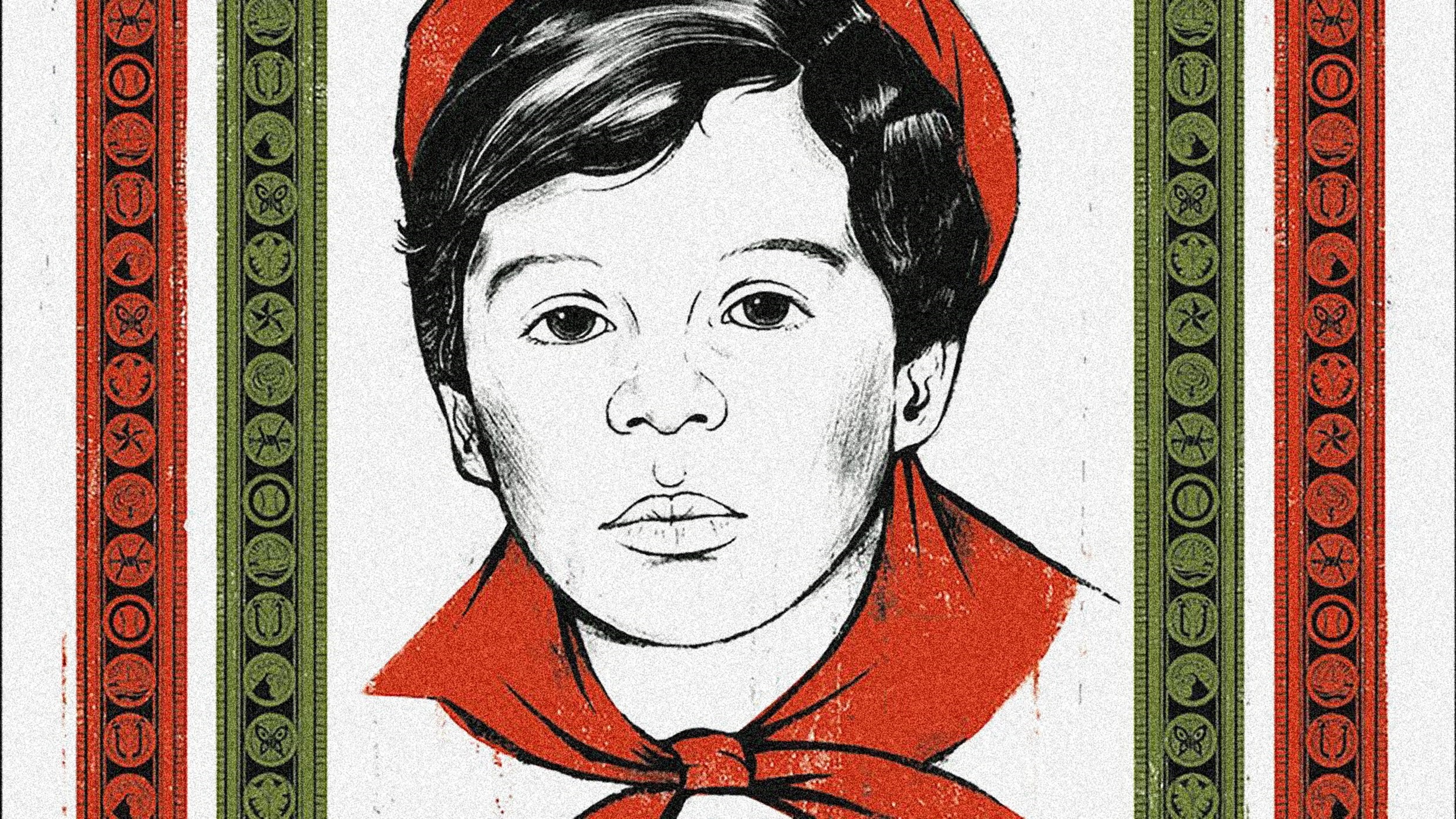

Worm begins with the Cuban Revolution and is followed by Rodriguez’s birth in 1971. It vividly renders his childhood in the newly Communist country, with all of its highs and lows. It’s a story deeply rooted in a time and place—and one that fascinates in its level of detail and insight. With an upstart photography business and black market dealings, Rodriguez’s father’s entrepreneurial spirit caught the attention of the omnipresent eyes of the party. Meanwhile, the indoctrination happening to his kids at school haunted him. So amid threats and paranoia, the family fled the country—becoming “worms,” a Castro slur for the “traitors” leaving the island—on the 68-foot shrimp boat Nature Boy in 1980. They eventually arrived in Miami disconnected from family and everything they knew.

Rodriguez drew inspiration from the work of Cuban-born writer Mirta Ojito and Persepolis, not to mention classics like Animal Farm and 1984, which he first read when he was a young teenager.

“When I read those two books, I just thought, OK, there’s my life,” he says. “As I was trying to figure out what the hell had happened to my family, I picked up those books and was like, my God, here it is. It’s right here, everything we just went through. I think in the U.S. they’re read as some sort of odd fiction, but to a lot of us, it’s really what life was like.”

Having never worked on a memoir or long-form project of this scope, Rodriguez didn’t study the form of the graphic novel, but started by assembling a scrapbook of pictures and sketches. He then wrote the text, workshopped it with his editor, and was ultimately free to illustrate and design the book however he best saw fit.

“I wanted every page and every spread to be something that you looked at for a while and you spent time on,” he says. “That was my goal—rather than something airy, I wanted something very heavy that you had to really think about.”

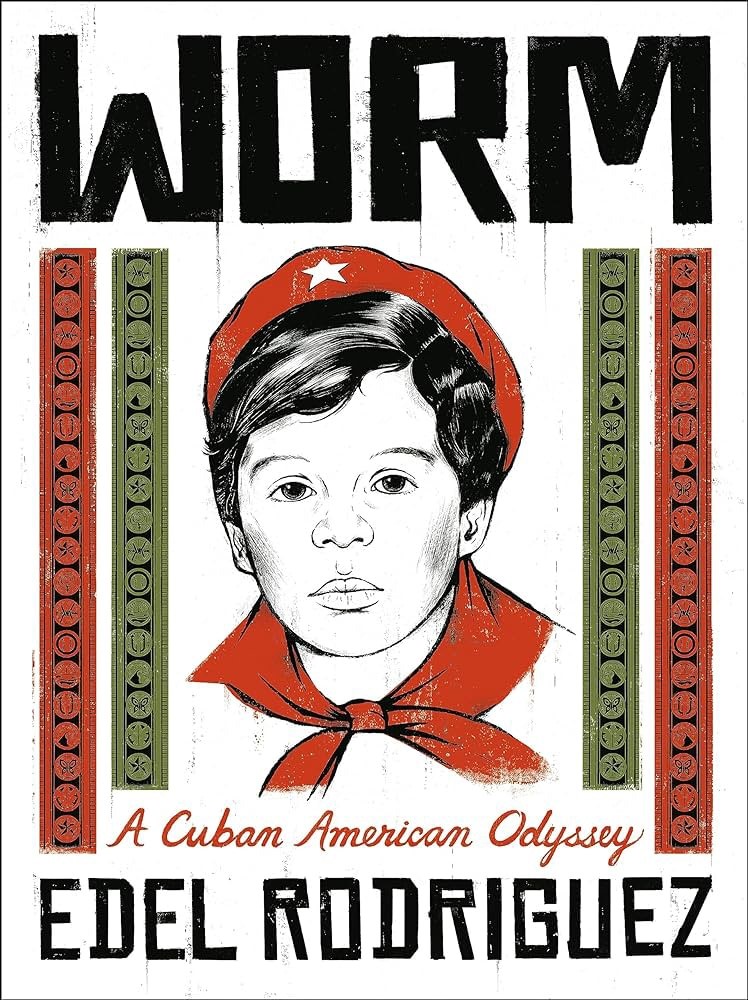

The color palette is one of the most striking parts of the book. Instead of depicting Cuba in all its kaleidoscopic hues, he adhered to a restrained approach because he found that the more he added, the more it distracted from the writing. He began with red—a color traditionally associated with communism.

“I’ve actually used it in my work a lot because of that, because I don’t like the idea that a dictatorship can decide what colors they own,” he says.

Given the military dominance in the country and the camp his family was held at before they finally left the island, he then added green and only selectively invoked additional shades from there. (You can probably guess what color flares up around 2016.)

Collectively, it makes for a striking mosaic of memory that infuses vibrant life into history and events that so many of us stateside have long taken at face value. And on the eve of the 2024 election, it’s a powerful reminder about the dangers and outcomes of extremism—not to mention the human cost of it.

Inevitably, Worm also sheds light back on its creator.

“[It might] help people understand why I’ve done the work that I’ve done here in the United States,” he says. “Because I have this background that makes me see things in a different way.”

(16)