Innovation is at the heart of wealth creation. Innovation is at the heart of job creation. Innovation is at the heart of building better lives for everyone. And innovation can be increased by conscious support.

Innovation is enhanced by a culture of innovation, encouragement of talented inventors and entrepreneurs, collaboration between academics and business people, and proactive investing.

A lot of people don’t think innovation is important. It is disruptive—businesses can fold and people may lose their jobs. People may need to learn new skills.

But the world needs innovation for people’s lives to improve and be satisfying. In Seattle, we’ve certainly seen the fruitful results of innovation over the years with the cascading successes of Boeing, Nordstrom, Microsoft, Costco, Starbucks, and Amazon. Seattle is also at the forefront of using innovation to improve global health through such local institutions as the Gates Foundation, PATH, UW Medicine, and the Hutch.

Important discoveries are also being made regularly at the University of Washington (UW) and these are being translated into new businesses and products and services.

Important for innovation is having a culture that allows people to invent and to become entrepreneurs. The UW has done a good job in recent years creating an environment where students, faculty, and researchers are encouraged to create, to see the world as it can and should be.

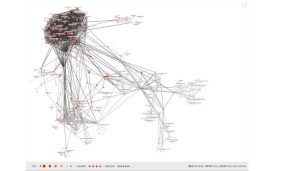

Part of this culture also allows people to ask the big questions—just like Bill Gates or Jeff Bezos did. A personification of this cutting-edge intellectual ecosystem is Carlos Guestrin, the Amazon Professor of Machine Learning in the UW’s Computer Science & Engineering Department. In addition to being a great professor, he was also co-founder and CEO of Turi (initially named Dato and GraphLab), which focuses on large-scale machine learning and graph analytics and was recently acquired by Apple.

Being an innovator doesn’t always mean launching your own entrepreneurial venture. You can be an innovator in a huge and rapidly expanding company like Amazon. And you can adopt and embrace an entrepreneurial attitude no matter what job you have—even if you’re a mid-level government employee in a large, cumbersome public-sector bureaucracy.

It helps if you are surrounded by other innovators, but, if not, be one of those innovators who starts their own revolution.

Innovation is also about the failure that often comes before success. In many corporate and other cultures, failure is a badge of shame. It shouldn’t be. Instead, it should be an indication of education, of important lessons learned that can be meaningfully applied the next time—or the time after that.

Having said all this, we need to realize that innovation is hard. It’s usually a rough path. That’s why I think our job as venture capitalists have something in common with professors at the UW: We have to help aspiring innovators to pursue their dreams notwithstanding obstacles and disbelievers.

It’s more than money. Venture capitalists, business people, and professors can provide fledgling innovators with essential advice and access to additional resources such as technical and marketing help.

Creating cultures of innovation and investing time and money in the innovators of tomorrow are important if we are going to generate and sustain prosperity.

Editors note: This essay is one in an occasional series appearing in the Xconomist Forum, written by contributors selected by CoMotion, the University of Washington’s innovation hub. To learn more from UW innovators, visit uw.edu/innovation.

(47)

Report Post