— July 26, 2017

Tuan86 / Pixabay

Productivity is the defining word of the modern workplace.

It’s nearly impossible to read any business-focused blog and not come across an article on yet another productivity “hack”. Pop into your nearest bookstore and you’ll find rows upon rows of books promising to improve your productivity.

Yet, actual workplace productivity keeps going down year-on-year.

What gives? Are the usual culprits – social media and poor discipline – to blame? Or is there something else at play here?

In this article, I’ll dig beyond the superficial “hacks” into the fundamental reasons for productivity and procrastination.

You’ll learn:

- The psychology of productivity

- The relationship between willpower and productivity

- Why multitasking is a myth

- How making decisions affects your productivity

- How to use psychological effects and biases to improve productivity

Understanding Your Brain

Poor productivity is seldom the result of laziness, at least not in creative workers and entrepreneurs.

Rather, the underlying causes of poor productivity are often associated with how, where and why we work.

Understanding the psychological basis of productivity, therefore, can help you improve productivity as well.

Below, I’ll share a few critical concepts that determine your work habits and productivity.

Willpower is a Finite Resource

To a society obsessed with quick fixes and hacks, “willpower” sounds like an anachronistic, Victorian-era word. It feels strangely mystical – an undefinable quality that’s hard to find and even harder to acquire.

Yet, nothing affects your productivity more than this “dated” concept.

There has been a resurgence of late in the study of willpower and “ego depletion”, led by psychologist Roy F. Baumeister.

In Baumeister’s most well-known experiment, a group of test subjects was asked to choose between radishes and chocolates before attempting a difficult puzzle.

Subjects who forced themselves to choose radishes – that is, exercised their willpower – quit substantially faster than those who chose chocolates.

Baumeister found similar results across several experiments and test subjects.

In another experiment, test subjects were divided into two rooms and asked to solve a puzzle. The scent of freshly baked cookies was channeled into one of the two rooms.

The experiment found that test participants who had to fight off the temptation of the cookies gave up far earlier on the puzzle than subjects in the other room.

The conclusion from these cookies-and-radishes experiments was the same: willpower is a finite resource.

You start each day with a limited supply. Each decision you make or temptation you resist depletes your willpower (a term Baumeister called “ego depletion”).

This is the reason why you feel indecisive and indolent after 8-10 hours of work. It’s not just that your body is exhausted – your willpower is spent as well.

Luckily, willpower, like other muscles, can be trained. It can also be channeled and managed to help you get the most from your day.

I’ll show you how to tap into this hidden strength later.

The takeaway: Willpower is finite. Conserve it so you can use it for decisions and actions that truly matter.

Making Decisions Exhausts Your Energy

Mark Zuckerberg has a net worth of over $ 60 billion.

Yet, it’s hard to find a picture of him where he is not dressed in his trademark gray outfit.

Besides the branding benefits (picture Steve Jobs in anything other than a black sweater and blue jeans), there is a major reason why Mark Zuckerberg and thousands of ultra-successful people wear the same outfits:

As Barrack Obama says about his sartorial choices:

“You’ll see I wear only gray or blue suits,” [Obama] said. “I’m trying to pare down decisions. I don’t want to make decisions about what I’m eating or wearing. Because I have too many other decisions to make.”

Ergo, making decisions is mentally taxing.

A particularly illuminating study on decision fatigue comes from an analysis of a parole board’s decisions.

After studying 1,100 decisions over a year, the researchers found prisoners who appeared early in the morning had their parole approved in 70% of the cases.

Prisoners who appeared late in the evening, however, had only 10% parole approval rates.

The decisions had less to do with the prisoners’ crimes, race, age or religion. Rather, it was highly related to how many other decisions the parole board had taken in the day. The parole board’s members were more likely to consult others and think through a decision early in morning.

By the late evening, their willpower was exhausted and they were likely to make a quick decision. Hence, the low approval rates.

I’ll show you how to use decision fatigue to your advantage later.

The takeaway: Every decision you make has an energy cost. The more you can minimize decision making, the better decisions you’ll make.

Multitasking is a Myth

The human brain is incapable of multitasking.

Writing in PsychologyToday, Matthew MacKinnon, MD notes:

“Science has consistently shown that the human brain can only sustain attention on one item at a time…our overestimation of our attentional capacity stems from a fundamental misunderstanding of the concept of multitasking and of the human attentional system as a whole.”

Yet, the belief that you can multitask effectively holds strong, much to the ruination of your productivity.

According to a landmark study in cognitive function and multitasking, the human brain goes through two stages when switching between tasks:

- Goal shifting:

- Rule activation:

Because the brain has to move between these two stages rapidly in multitasking, it takes a toll on your cognitive ability. This is called “switching cost”.

The more different the two tasks, the higher this cognitive cost since the brain has to shift goals and activate an entirely new set of rules.

The takeaway: Outside of a rare few people, multitasking is cognitively impossible for the brain. It makes you less focused and more likely to fail.

Don’t multi-task, unless the tasks are extremely closely related.

Procrastination is a Coping Mechanism

Procrastination is an age old human problem. No less a genius than Leonardo Da Vinci was known as a chronic procrastinator.

Procrastination is usually dismissed as a time management issue. There is even the assumption that procrastinators are lazy or unmotivated.

Yet, procrastinators are often happy to work, just not on the problems that actually matter.

When you dig deeper into the root cause of procrastination, you realize that procrastination is less an issue of self-regulation than it is of emotion regulation.

In an academic study of high-school students, it was found that the perceived threat or harm of a task was highly correlated to procrastination.In another study, procrastination was tied to students’ self-perception and self-esteem. Students who believed they were going to succeed were more likely to attack a task than students who felt they were going to fail. As psychologist Tim Pychyl notes:

“Psychologists see procrastination as a misplaced coping mechanism, as an emotion-focused coping strategy”

Ergo, you put off plans and difficult tasks not because you are lazy, but because you are scared of the complexity or the end results of the task.

If you’ve ever decided to arrange your closet or mow the lawn instead of writing a blog post or making a marketing plan, you already know how this feels.

The takeaway: Before you use time management tactics to change your procrastinating habits, solve the emotional foundation of procrastination.

5 Strategies to Become More Productive

Once you understand the psychological factors affecting your productivity, you can also take steps to manage them.

Below, I’ll share my top five strategies to use to improve your productivity:

1. Focus on Energy Management, Not Time Management

As Baumeister’s research reveals, your willpower is a function of your energy levels. The less energy you have, the more prominent is the “ego depletion” effect.

This is the reason why you are more likely to indulge or disengage when your energy levels are low.

To counter this ego depletion effect, focus on managing your energy through the day, not your time. You will find that when you have more energy, you are also able to channel it better to tasks that truly demand your attention.

For instance, when 106 employees at Wachovia bank took part in an experiment focusing on energy management, they reported a 20% gain in a KPI. 68% also reported a positive influence on their relationships with customers and colleagues.

How you manage your energy is subjective. However, the following can help:

- Take frequent breaks: One study concluded that the optimal work-break time was 52 minutes of work followed by a 17-minute break. Use a customized Pomodoro timer to manage your work and breaks.

- Sleep more: Research shows that sleeping a minimum of 7+ hours a day improves everything from memory to athletic performance. Even taking 60-90 minute naps during the day has similar effects.

- Take more vacations to rejuvenate energy levels. In one study of its employees, Ernst & Young found that for each additional 10 hours of vacation time, employee performance ratings improved 8 percent.

- Manage what you eat. Baumeister’s research shows that a simple sugar snack can help replenish energy levels and improve willpower.

And as always, exercise. Regardless of the situation, exercise improves focus, memory and energy.

2. Manage and Manipulate Your Willpower

While the connection between willpower and energy holds true, a whole new body of research has given us a more nuanced understanding on willpower.

For example, Michael Inzlicht’s research at the University of Toronto shows that willpower is like an emotion. That is, it can be manipulated and managed.

Just as your emotional state can be contoured by your self-talk, your willpower, too, can be shaped by self-affirmation. Simply telling yourself that you will reward yourself with, say, a cup of ice cream, can help you push through a difficult task (even if the reward doesn’t actually materialize).

Another landmark study in willpower management comes from a Columbia University professor, Walter Mischel.

Mischel’s now-famous “marshmallow” experiment led to the development of the “hot and cold” framework for explaining willpower. In this framework, the “cold” system is cognitive and rational. The “hot” system is emotional and irrational.

When willpower fails, the presence of a “hot” stimuli leads to people acting on an impulse. In the absence of such a stimuli, however, the “cold” system gets time to rejuvenate and take control.

Mischel’s research ultimately concluded that if you can manage environmental stimulus, you can also manage willpower. That is, the fewer “hot” stimuli you have around you, the less likely you are to fail.

Here’s what you can conclude from these two studies:

- The suggestion of a reward – real or imagined – can compel willpower rejuvenation.

- By reducing the number of distractions around you, you can manage your willpower better.

3. Regulate Decision Making

The more decisions you have to make, the more you deplete your willpower.

To avoid decision fatigue, create a system where the majority of your decisions are either automated or set to a “safe” default.

For example, instead of buying multiple cereal boxes and choosing between them each morning, buy a single cereal variant. This then becomes your “default” breakfast choice, removing the need for decision making.

Similarly, you can create a system where your decisions are automated based on fixed parameters. For example, instead of manually deciding which emails to archive, you can use IFTTT to automatically save emails that contain a particular keyword(s).

Other examples include using a meal service for lunch, setting up automated alarm systems, etc.

The key is to minimize the number of trivial decisions you make. By carefully controlling your available choices, you can ensure that you conserve energy for decisions that truly matter.

4. Use Psychological Effects to Your Advantage

An easy way to start any project is this:

Just start.

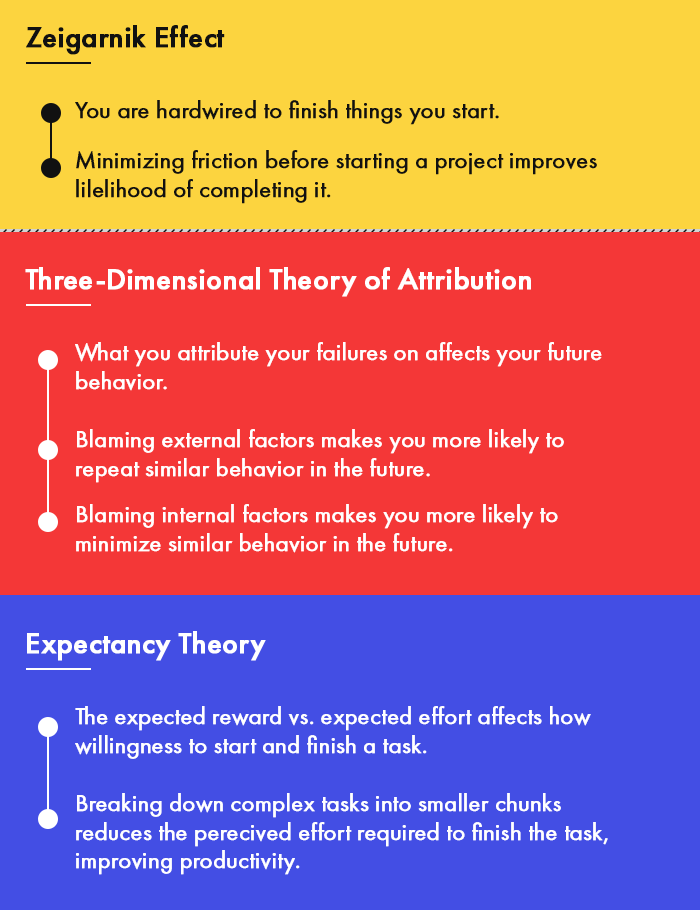

As simple as it sounds, there is a psychological effect behind this piece of advice: the Zeigarnik Effect.

According to this effect, we are hardwired to not leave things unfinished. Once we invest time and energy into a project, we feel compelled to finish it.

This is one of several ways you can improve productivity by taking advantage of our innate psychological biases.

Another example is the three-dimensional theory of attribution.

This theory states that how we explain our behavior determines our future behavior. In an experiment, students who blamed external factors for their poor scores were more likely to score poorly in future tests.

However, students who took the blame on internal factors (lack of studying, poor time management during the test, etc.) showed better results in the future.

The conclusion: if you want more self-control, accept the blame for the loss of self-control. The more you externalize the blame, the more likely you are to repeat it.

Another effect you should be aware of is the Expectancy Theory.

According to this theory, how energized you feel about a task depends on its expected rewards vs. the effort required to achieve it.

While you can’t change the rewards of a task, you can change the perceived effort to achieve it.

By breaking down a complex task into various smaller, more achievable parts, you can trick your brain into perceiving the task as easier than it is. A smaller task also reduces friction in starting, making you more likely to stick until it is finished.

5. Control Your Work Environment

There is a massive body of research showing how your work environment affects your productivity.

There are some factors of your environment beyond your control (you can’t choose between open vs. closed offices in most companies, for instance).

However, by carefully managing a few simple things, you can improve productivity drastically:

- Reduce the resistance to start by leaving your most important documents, applications and tools in a “ready state”. For instance, if you are writing an article, leave the laptop open on the document before you go to bed at night.

- Work in a public environment where you are being monitored. The Hawthorne effect states that people are more productive when they are being observed. If you are working alone, try doing it in a coffee shop or co-working space.

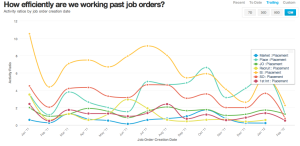

- Tracking productivity also helps improve productivity. Use a tool like RescueTime to automatically track your activities. Compare your productivity over time to detect gaps and areas of improvements. You can try these tools to improve productivity as well.

- Listen to music that improves productivity, mostly ambient sounds and simple, repeating motifs. Look up “homework edit” on YouTube or use tools like Noisli. Music is particularly effective at making repetitive tasks more enjoyable.

- Lastly, don’t multitask, unless the tasks are a) simple, b) repetitive, and c) closely related.

For creative managers, McKinsey’s article on creating a state of “flow” is particularly pertinent. By carefully managing the quality (IQ), emotional energy (EQ) and desired output (MQ) of a team, you can induce a state of “flow” that’s associated with higher productivity.

Conclusion and Key Takeaways

Productivity is a common concern for most businesses, managers and creative individuals. Yet, the path to achieve it often feels confusing, if not impossible to navigate.

The solution to this problem is to first understand the underlying causes of poor productivity, and to then take steps to address them.

A thorough understanding of your brain and its motivations are particularly helpful in this regard. As you saw above, willpower, ego depletion, decision fatigue, etc. all affect your productivity.

You can mitigate these issues by:

- Controlling your work environment to create a more productive office setup.

- Using psychological effects such as the three-dimensional theory of attribution, Expectancy theory and Zeigarnik effect to “cheat” your way to productivity.

- Automate decision making to minimize decision fatigue.

- Focus on managing your energy levels throughout the day instead of managing your time.

- Control your willpower by using rewards and managing distracting stimuli around you.

Business & Finance Articles on Business 2 Community

(82)

Report Post