By Janko Roettgers

Next week, Netflix’s longest-running show is slated to return for a new installment—and no, we’re not talking about Grace and Frankie.

For ten years now, Netflix has been distributing its quarterly earnings calls as video interviews, with multiple execs bantering with an analyst on camera. Tens of thousands of people watch these calls every quarter, far surpassing the interest in other public companies’ earnings calls, and Netflix executives have over the years learned to put on a show.

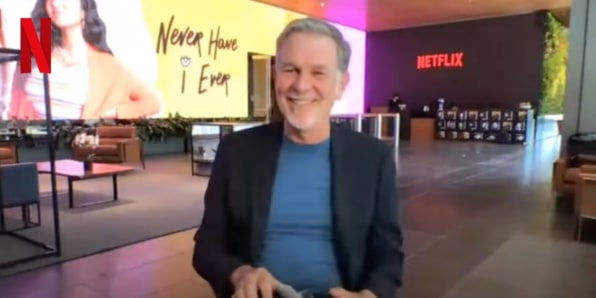

Former CEO Reed Hastings used to show up in themed apparel, including a Squid Game tracksuit and a Stranger Things ugly holiday sweater. Executives regularly joke about their love for guilty pleasure shows like Too Hot to Handle, and occasionally even veer into off-color territory. In early 2014, Hastings joked that then-HBO CEO Richard Plepler’s streaming password was “Netflix b*tch,” leaving the analyst conducting the interview momentarily speechless.

Eight years later, Hastings interrupted a fellow executive mid-sentence to announce that the company was looking to launch ads on its service—a major shift for its business model. “Reed basically blurted it out during an earnings call,” says veteran media reporter Peter Kafka.

Netflix’s earnings calls are unlike those of any other public company—and it all started with a faux pas and a slap on the wrist.

Like fireside chats—with crappy webcams

In July 2012, Hastings took to Facebook to reveal that the company’s customers had streamed more than one billion hours of programming during the preceding month. This was an exciting milestone for the company, but revealing it on Hastings’ personal Facebook page got the company into trouble with regulators, who alleged that it was violating public company disclosure rules.

The Security and Exchange Commission briefly threatened Netflix with an injunction, but ultimately let the company off the hook with a warning, and clarified how companies could use social media to distribute information for investors going forward. A year later, July 2013, Netflix used the rule change to conduct its first earnings call as a live video on YouTube.

“We’ve always admired the fireside chat format at investor conferences as being the most dynamic and interesting,” Hastings told viewers at the beginning of that call. “This is our attempt to bring that value to the broad online public.”

Hastings leaned in close to his laptop webcam for this first call. “I hope the quality is acceptable,” he said, while someone in the background could be heard adjusting their computer’s volume. Lanky and with a tendency to slouch, Hastings barely kept his chin in frame as the call continued. Unflattering lighting, hissing microphones, and a barren, off-white wall completed the picture. Had the notorious Room Rater Twitter account been around back then, it would have compared the performance to a hostage video.

Netflix got beaten to the punch

That first call wasn’t merely marred by technical issues: It also came a few days too late. Netflix executives really wanted to be first to use video for earnings calls, according to a source familiar with their thinking at the time who spoke to Fast Company under the condition that we don’t identify them by name.

Four days before they got their wish, Yahoo’s then-CEO Marissa Mayer did her own video earnings call. However, Yahoo’s more tightly choreographed presentation, which made use of an anchor’s desk and teleprompters, felt stiff and scripted, with some likening it to a Saturday Night Live parody. Soon after, Yahoo returned to a traditional earnings call.

The post-earnings conversation with analysts, which most of corporate America follows, is a tried-and-true format that hasn’t seen much innovation over the years. Audio-only conference calls typically start with some classical music while everyone waits, an investor relations employee recites a laundry list of regulatory disclaimers, followed by prepared remarks from the CEO, and finally a dry Q&A session with those analysts.

“There are a lot of standard parts in earning calls that are just a stupid waste of time,” says Kafka. He actually got invited as an interviewer to a few of Netflix’s early video calls, when the company was still pairing journalists with analysts. “The pitch was: You get to ask whatever you want,” Kafka recalls.

Eventually, Netflix settled on having just one analyst facilitate the interviews. The company also invested in proper cameras, lighting, and sound, and ultimately began to prerecord the calls to deal with quality issues before uploading them onto YouTube—a change that has resulted in some reporters watching the videos at double speed to be first to discover any juicy bits.

A new era for Netflix’s earnings calls

The early days of the pandemic saw a brief return of less polished earnings videos for Netflix, as executives briefly dialed in from home. Since then, the company has settled on a formula—and a set of frequently reused backgrounds—that give the calls a more professional look. In a way, the evolution of the company’s earnings call format mirrors its development from a feisty streaming pioneer to a massive incumbent with hundreds of millions of customers.

Coinciding with this, Netflix earnings calls have also lost one of their biggest wild cards: Hastings transitioned out of the CEO role at the beginning of this year, and he announced on the Q4 2022 call that going forward he wouldn’t be in front of the camera anymore.

However, Hastings didn’t seem ready to quit the show altogether. “I will be in the prep sessions,” he promised. Maybe he’ll even be able to convince his successors to wear an ugly sweater every now and then.

Netflix’s next earnings call is scheduled for 3 p.m. PT this coming Wednesday.

(36)

Report Post