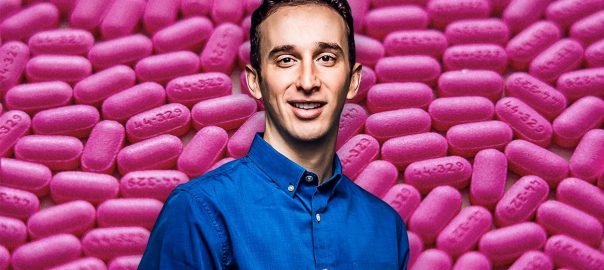

You don’t bet against Zach Weinberg. In 2010, at age 24, he sold Insight Media, the display advertising and exchange bidding company he cofounded with Nat Turner, to Google for a reported $81 million. Their next venture, Flatiron Health, a data-science software company that pioneered the use of so-called real-world evidence in medicine, was acquired by Roche in 2018 for $1.9 billion.

In the time since—including a long, boring stretch of pandemic—Weinberg has been advising founders via Zoom and making small investments in startups, including ones trying to develop new medicines. Struck by the challenges they faced, from getting people to answer their emails to the dispiriting 90%-plus failure rate for new drugs, Weinberg gathered partners and mustered not-inconsiderable resources to launch a new venture: Curie.Bio, which was officially unveiled on February 14.

Curie—named for double-Nobel-winning scientist Marie Curie—aims to work with founders as a drug discovery “co-pilot” and seed investor, helping them to overcome the usual hurdles, develop cures, and launch great companies. A unique combination of two business entities—one providing a range of science consulting services, another providing startups with seed funding—Curie has raised a total of $520 million from investors that include GV (Alphabet’s venture arm), ARCH Venture Partners, a16z bio+health, Casdin Capital, and NexTech.

We recently spoke with Weinberg about costs, complexity, and innovation in drug development—and the promise of new platforms and funding models to accelerate progress.

Fast Company: What’s wrong with the way drug startups work now?

Zach Weinberg: Unlike in software, you can’t start a therapeutics company in your garage. You can build a pretty good software company with a few million dollars and a little bit of help. But biotechs have been really, really expensive to start because, typically, you needed to build a lab and invest a lot of work and effort just to get to the first experiment. It has complexities that are nothing like software, and mistakes in early-stage drug discovery are very expensive.

As a biotech founder, you’ve traditionally had two choices, neither of which are particularly great for you as a scientist. You can go to the large-scale incubators—the Flagships and Third Rocks and Column Groups [large biotech venture firms]—and they will help you make fewer mistakes, but they own most of the equity. Or, you can go to a classic seed-stage venture firm, writing smaller checks, so you retain more ownership, but maybe one partner who has true drug discovery experience. So, you’re more likely to make mistakes.

FC: And Curie Bio is, essentially, a third way?

ZW: We are basically a deep accelerator that is focused exclusively on therapeutics. We have a very large team of drug discovery scientists—it will be close to 60 over the next year and a half—and we are also making seed investments out of a $270 million fund. What Curie really does is enable you as a founder to make much more progress for less, because we surround you with the expertise, the people, the vendors, [and] the access you need. Because we’re writing smaller checks—typically $5 million to $7 million—you ultimately retain control and ownership of your own thing, and you can still raise more later. I kind of view our job as getting you to the series A.

FC: Why hasn’t anyone done this model before?

ZW: For one thing, it’s logistically difficult to set up two different entities and raise half a billion dollars for an idea. But another part of what is going on right now is that costs are coming down. Where in the past you had to spend tens of millions of dollars to get to your first experiment, now you have an ecosystem of vendors that can run that experiment for [more cheaply] either the next day or at the least next week. There are dozens of these preclinical CROs [contract research organizations]—from SHI to Pharmaron to Evotec to ChemPartners—that didn’t really exist 10 years ago or, if they existed, kind of sucked. And they’ve just matured. I think that’s the pull of capitalism—servicing biotech and pharma is a good business, so these businesses got better at doing it, and they got bigger so that now you have economies of scale.

FC: So, biotech startups don’t even need a lab now?

ZW: They may have a lab, but it can be a lot smaller. It’s like the shift to cloud computing. In the beginning, people were like, why would I ever put my servers on Amazon? And now they’re like, why would I ever not do that? Now, what you need to do as a biotech founder is to design the right experiment and make sure you find the right vendor to do it. There’s a long, long list of enabling technologies that make pursuing an idea in drug discovery more viable. Our hope is that, obviously, that won’t remain static. The tools that we have are getting better, the costs are coming down, the vendors are getting better.

This should be a dawn of new ideas. It should be an area where great creative ideas are rewarded. But the complexity remains high. The ability to determine the right strategy, to look at your data properly—there are still so many places you can make a mistake. That’s where we think Curie is filling in a missing piece.

FC: Who’s actually on the team?

ZW: We have about 20 to 25 people now, and almost everybody has been involved in a drug discovery startup before—in the weeds and in the science team, not in the marketing team. I’m basically the only one without a PhD. Getting Alexis [Borisy] and Christophe [Lengauer] to join as cofounders was key to the whole thing. They came from Third Rock. Frank Stegmeier was CSO of a company called KSQ Therapeutics; Greg Carven was the CSO of a biotech called Scholar Rock, and he actually originally discovered [Merck’s cancer drug] Keytruda back in the day at Organon. Our pitch to founders is, we’ve been in your shoes, literally. We’ve made all the mistakes. We’ve hopefully made some good decisions, too.

FC: What kinds of problems can you help founders solve?

ZW: We help with experimental design, of course. If you need space, we’ll help you get space. You need this vendor, we’ll help you get them. If you’re using a vendor and we check and see that their works sucks, we’ll find you another one. We send out the RFPs and sign the contracts with the vendors. We do actual work. We don’t just send email introductions.

FC: Are you looking for anything particular in terms of disease targets or founders?

ZW: We’re not doing digital health, we’re not doing diagnostics, we’re not doing pure software plays. Our target market is that the thing you ultimately make is a potential drug. We’re going to try and go meet founders wherever they are. As long as the company can be legally formed and there’s no weird IP ownership things going on, there’s no reason you can’t do the vast majority of this stuff from anywhere. Our first four companies are U.S.-based, but from all across the country. The big therapeutic areas are, of course, oncology, immunology, and inflammation. We’ll look at rare disease and any area we believe is big enough, frankly, that a large company would be interested in it. Because ultimately, we are reliant as everybody on the next round of funding.

The number one thing we care about is can we get you to value inflection—some meaningful milestone, usually data from experiment—in about 18 months for about $5 million to $7 million? That’s probably not a new gene therapy with a novel delivery method. But it could be a small-molecule drug, biologic, engineered protein, or potentially a nucleic-acid driven therapy or even cell therapy. Wherever we’ve industrialized the infrastructure, the costs come down, and more and more things come into scope.

(12)

Report Post