Two weeks ago, Buffer’s co-founder Leo Widrich gave an interview to TechCrunch about the transparent culture embraced by his company. Buffer is going to great lengths to make information about the company easily accessible to everyone: from salaries to revenue and churn, everything is public. When asked about the results of this policy, Joel was unambiguous: “It’s been incredible”.

In the last few months, these kinds of stories about transparency at work have flourished, and the conclusion is almost always the same: transparency is beneficial to the organization. However, very little effort has been dedicated to explain why is this transparency so beneficial. It is often suggested that a transparent culture seems more humane and as such, allows the company to stand out and attract better talent.

I don’t think this assumption is right. It’s not so much about the culture, or about people feeling valued and listened to. I think those traits are important and should be expected, but they’re not a consequence of a transparent organization. I can think of huge, immensely successful companies that are known for their non-transparent cultures. I’d be surprised to learn that Apple employees feel like their work is not valued.

The reason you should set transparency as a goal for your company is because it can be your decisive advantage over the competition. Transparency is all about speed of execution. Transparent organizations move faster than their “opaque” equivalents, and as ex-Googler Dave Girouard puts it: “All else being equal, the fastest company in any market will win”.

Communication & transparency: two ways of sharing knowledge

People live different lives. They learn different things, from which they form different views of the world. When they decide to sync with one another, they need to share the experiences they had. How was the client demo? Are the numbers on target? Is the new hire performing well? The intuitive way to address those questions is the direct, active form of communication: send an email to the relevant group of people, hold a meeting, get on a call, etc.

This kind of communication is slow. You have to provide context, give a general idea of what is going on, but also dive deep into details so that no ambiguity remains. Communication is an iterative process, with each party bringing a new piece to the puzzle one after the other. The process must continue until doubt or disagreement is impossible. If you’ve ever played a game of Guess Who?, you know it can take some time before you’re confident enough to guess a name. In a sense, every attempt at communication is like a small game of Guess Who?

Show, don’t tell

Transparency, on the other hand, can cut through all that. It is nothing but a shortcut for communication. First, it operates instantly. Try playing Guess Who? with the two players on the same side of the board: suddenly, it’s a lot faster (and admittedly not a game anymore). Second, transparency also has the power to create “common knowledge”. Common knowledge is knowledge that not only everybody knows, but everybody knows that everybody knows, etc. up until infinity. This is the biggest time-saver! When something is common knowledge, it’s not talked about anymore: everyone knows that everyone knows about it.

The power of this cannot be overstated. The “sales target dashboard” illustrates that perfectly. We’ve had one at Front for a month now, and things have changed. Not only does the sales team know exactly how far they are from target: now they know that if they’re behind, the engineering team can see it as well. This feeling of accountability presses them to focus on the objective. Conversely, when engineers see that sales are behind target, they know that requests from the sales team have high priority, and don’t put it off to work on fun stuff. Everybody wins. (If you feel it’s not fair for the sales team, rest assured: we’re working on the engineering side of the dashboard so that everyone can see when Front is up or down :).

It works just as well with “external transparency”. By making some information accessible to people outside your organization, the productivity gains can be substantial. Our product roadmap is public, which has the double advantage of speeding up both user feedback collection and product management. The product decisions we make are easy to justify internally, and we can prioritize development in accordance with user’s’ requests. We’ve effectively solved the “What would you say you do here?” problem from Office Space:

The checklist

I put together a checklist of things we successfully adopted at Front to make our organization more transparent, and ultimately more efficient. Those should be easy to implement and none of them have backfired significantly (more on that at the end of the article):

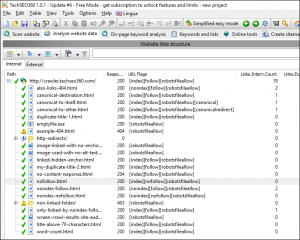

- Dashboard. I already mentioned the benefits of the dashboard. We tried a couple vendors and ended up using Geckoboard, which allowed us to have something live

- Chatrooms. We use Slack, and people mute the channels that aren’t directly related to their job, but being able to notify and get notified from any conversation certainly helps a lot in making sure that everyone has the needed context available at all time.

- Frontdesk. What Slack is bringing for our internal conversations, Front does for conversations with the outside world. sales@, suppport@, jobs@, founders@, Twitter, everything is accessible to everyone.

- Product management. Trello has nice little features to strike the right balance of openness: you can lock some cards, and put others for vote; you can mention and assign. That’s what we used to build our public roadmap.

- For every other tool, Meldium lets you grant access to anyone in your organization (and you can fine tune it to suit your needs).

Know where to stop

Transparency is a tool, not a dogma: it can speed up your work, but it must not be blindly implemented. In some cases, achieving transparency is impossible, and by trying to disclose as much information as possible without being able to give the full context, you end up with very counter productive results.

The “public salary policy” is the epitome of that. Employee compensation is very context-dependent: what might look unfair on paper can be easily explained in a 2-minute conversation. However, once you’ve made the compensation grid public, unless you take the time to provide the entire context of each and every number, you will end up with a constant stream of questions to clarify this and that. On the other hand, you will lack the flexibility you might need to convince the right people to take a job, or if you do, your system will look arbitrary and even less fair. Rule of thumb: if disclosing information on a topic raises more questions than it answers, it’s not a good candidate for transparency.

Business & Finance Articles on Business 2 Community(121)

Report Post