New technologies, economic uncertainty, and a desire for greater flexibility are pushing more Americans into self-employment, especially those that have historically faced greater barriers to starting a business.

According to a recent study conducted by software company Gusto, there were 5 million new businesses created in the U.S in 2022—up 42% compared with pre-pandemic levels. Furthermore, while 71% of new businesses were founded by men in 2019, both 2022 and 2023 saw a near even split across gender lines. The share of Black entrepreneurs also tripled from 3% in 2019 to 9% in 2022, before backsliding slightly to 5% at the start of this year.

“There’s been this trend of people who previously had been left out of new business ownership driving this surge in entrepreneurship that we’re seeing today,” says Luke Pardue, an economist at Gusto who authored the study. “Everybody comes to entrepreneurship with their own perspective, their own idea of what problems to solve, and as we widen the net of the type of people who become entrepreneurs, the problems they identify and solve through entrepreneurship widens, as well.”

A solution for those most affected by economic uncertainty

Not only has there been a shift in who is starting businesses, there’s also been a shift in why. According to the study, inflation and economic uncertainty has been a major driver of new business creation, with 41% citing financial stability or supplemental income as their primary motivation—up from 24% last year. That number also rises to 56% among “side hustlers,” or those who maintain a business venture alongside traditional employment.

A change of lifestyle priorities and career burnout are also emerging as key drivers in new business creation. The Gusto study found that half of entrepreneurs quit a full-time job to start a business—up from 36% in 2021. Furthermore, 63% of the newly self-employed respondents made the change in pursuit of greater flexibility, while nearly half of entrepreneurs aged 35 to 54 started a business due to career burnout.

“The layoffs, the disruptions to schooling, the rising cost of living as inflation entered the conversation; the groups that are driving entrepreneurship are the ones that felt these disruptions to the greatest degree,” Pardue explains. “In 2020, Black and Hispanic workers and women were laid off at the highest rates, and they were the ones that turned that obstacle into opportunity by starting their own businesses.”

Though entrepreneurship has become more accessible to a more diverse segment of the population, financing opportunities have not. According to the Gusto study, 14% of new businesses founded by men received capital investment, compared to just 6% of those started by women. Furthermore, 10% of white business owners received outside investment, compared with 4% of Black and Hispanic entrepreneurs.

“A lot of the gaps in financing that are critical to growing and sustaining a business are still not available to many of the groups that are driving this surge in entrepreneurship,” says Pardue. “If we’re going to have equitable growth, we’re going to have to narrow those gaps.”

The entrepreneurs are all right

Research suggests that most self-employed Americans are feeling optimistic about their business’ near-term prospects, despite widespread concerns about the state of the economy among the general population.

According to the Gusto survey, 8 in 10 entrepreneurs say their business has performed better than expected, and those findings were echoed in a survey of solopreneurs (or those who own a business without employees) conducted by Collective, a platform designed to support that segment of business owners. According to the Collective survey, 81% report outperforming expectations in the last six months, while 83% are confident the next six will be the same or better. By comparison, a recent Pew Research poll found that 75% of Americans are concerned about the economy.

Collective CEO Hooman Radfar speculates that the disparity in economic outlook between the self-employed and the rest of the population is interconnected, as a slowdown in traditional employment often leads to more opportunity for entrepreneurs, and freelancers specifically.

“Businesses still need help, they just can’t take the risk to hire a full-time person right now, because they have uncertainty in the forecast,” he says. “Instead of having a full-time employee, they basically use contingent labor on a contract basis to work project by project as they figure it out.”

That theory is supported by the kinds of businesses that reported the greatest revenue growth, adds Radfar. According to the study, freelancers offering sales and marketing services saw their revenue increase 9.5% in the second half of 2022. Furthermore, Collective reports a significant growth in the number of consultants and coaches joining the platform.

“Whether it’s an agency or an individual consultant, the demand for that is growing,” says Radfar. “The areas where you see the most change right this second are areas where big businesses are shifting their spend.”

Why a lower barrier of entry can be a double-edged sword

Entrepreneurship rates tend to tick up in periods of economic uncertainty, but the rate of new business creation has been increasing more consistently and aggressively than in previous periods of volatility, which many attribute to a lower barrier of entry.

Historically, it has taken significant time and capital to take those first steps into entrepreneurship, but innovations—ranging from accounting software to online marketplaces—have made it possible to start a business in minutes at a little or no cost.

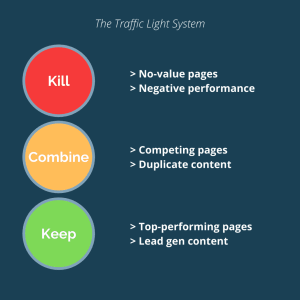

The rapid growth in entrepreneurship, the growing diversity of the self-employed population, and the economic optimism they report are all encouraging indicators, but less important than their ability to thrive long-term, according to Mahdi Majbouri, a professor of economics at Babson College.

“For many businesses, the barriers to entry have gone down, but competition is also getting more intense,” he says. “The entry rate is high; the exit rate could be high, as well.”

Majbouri, who is a coauthor of a report published by the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor—a global consortium of economists and academics who study entrepreneurship—says entrepreneurship rates fluctuate from year to year but have been trending upward over the last decade, especially among female and non-white business owners. At the same time, he cautions that the share of entrepreneurs within a given population isn’t itself a strong indicator of economic opportunity.

“I worry about, if someone has a good idea, would they be able to start a business around it?” he says. “The U.S. actually does really well in this area; if someone has a new idea that is good, they can bring it to fruition relatively easily.”

Majbouri adds that entrepreneurship rates are very high in emerging economies, but often due to a lack of more traditional work opportunities. He explains that in certain jurisdictions entrepreneurs can’t reach their full potential either, as their businesses are only able to grow so much before the government intervenes and takes control.

He says that an environment where people—and especially those that have historically faced barriers—feel like they have a chance to build a successful business is vital to a country’s long-term prospects. Despite funding gaps and other challenges that persist, he says the growing diversity of America’s entrepreneur population is encouraging.

“The most important thing is that people feel they have the same opportunity as everybody else . . . that their success rate doesn’t depend on which group they belong to,” he says. “It would be a virtuous cycle if more opportunities for any group come to fruition, because it entices more people to turn their ideas into business, especially among groups that are underrepresented.”

(9)

Report Post