The market will be key to fighting the climate crisis at the enormous scale needed, according to experts at the Fast Company Innovation Festival.

“What’s the one idea that humanity has come up with in the last 1,000 years that’s still transparent, cost efficient and verifiable?” asked Andrew Dailey, co-founder of Climate Vault, on the panel entitled Seizing the Last, Best Chance to Slow Climate Change. “It’s the market. So we said, ‘How can we take the market mechanism to address this problem’?”

The markets for buying and selling carbon offset are central to the Climate Vault’s mission. It buys permits allowing the emission of CO2 using funds from its partners, then “vaults” that carbon, reducing the amount of legally permissible emissions.

Next, the company, which was also co-founded by Michael Greenstone, previously chief economist for the Council of Economic Advisers for the Obama administration, invests in innovative carbon removal and sequestration technologies to permanently erase emissions from the Earth. “Our thing is really simple, which is: Tons, tons, tons, tons,” Dailey said. “And we end conversations with, ‘Let’s go get more tons.’”

For Dailey, the system works because of the scale it can achieve, comparing it to smaller actions that we do on behalf of sustainability in our everyday lives. “We all go home and compost our coffee grounds. The reality is, does the planet care?” he asked. “Composting is a wonderful thing…. [but] we’ve got to go after the big targets and do it in a cost effective way that’s durable, over the long term.”

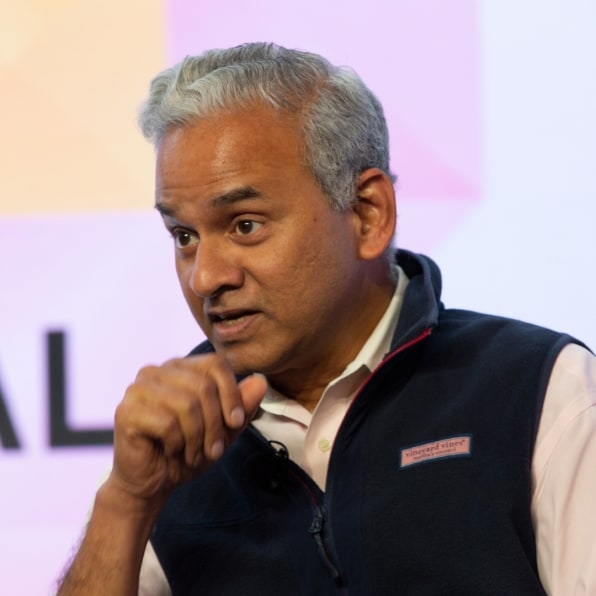

Supporting Climate Vault to scale its work is Genpact, a digital transformation company, whose data and insights will help the company reach a wider segment of the market, and work with bigger industries, to ultimately achieve its goal of reducing 10 million metric tons of emissions by the end of 2025. On the panel, Tiger Tyagarajan, Genpact’s CEO, agreed with Dailey about the approach. “Markets really work,” he said. “Bringing demand and supply together works.” And, it’s relatively easy for businesses to participate.

One such business partner is financial services company Northern Trust. “People will look at what Northern Trust has done and say, maybe we were too slow, because we weren’t the first out of the pack to claim we were going to be net zero carbon by 2050,” said Kimberly Evans, Northern Trust’s EVP and head of corporate sustainability, inclusion, and impact. But, the partnership is the result of a measured strategy that has involved all of its stakeholders. “It’s probably a little bit slower, but it doesn’t land us in a spot where we then have to pull back,” she said.

The company is still in early days, and there’s much to iron out. “We’re a two-year-old a startup,” Dailey said. “So I’m not confident in a lot of things.” It remains to be seen which carbon removal technologies will be most useful and effective. Direct air capture is promising, but there are many other candidates. “I don’t think we’ve got the answers just yet,” he admitted.

While markets will do the bulk of the work, Tyagarajan emphasized they will still have to be supplemented with policy. However unpopular at first, reasonable government mandates could help cut carbon tolls. He recalls when the world’s carbon footprint dropped in April 2020 at the onset of the pandemic, because everyone had to stay home. “No one sat down at the table and said, ‘Let’s negotiate a treaty,’” he said. “There was no treaty. You’re not getting out of your home, buddy. You’re not driving a car.”

That could inform future policy initiatives. For instance: “I wish there was a mandate that basically says, on Saturdays and Sundays, no one drives,” Tyagarajan said.

(13)

Report Post