Processes are a lot more interesting than you’d first think. That isn’t some kind of joke — they’re interesting, I swear.

Although they’re defined as “a collection of interrelated work tasks initiated in response to an event that achieves a specific result”, there’s a bit of a backstory that helps us cut through the corporate tranquilizers and understand what a process is, and why processes matter.

First, a few examples of processes:

- Cleaning the store

- Finding an email address

- Deploying software

- Customer profiling

- Onboarding a new employee

But why are those processes? Why aren’t they just jobs to be done? The point is that when you formalize a process, you think about the workflow with productivity in mind and it makes it easier to execute and optimize.

The first ever business process

The earliest known definition of a business process comes from Scottish economist Adam Smith. Breaking down his idea to the simplest elements, in 1776 he described a business process in place at a theoretical pin factory, involving 18 separate people to make one pin:

”One man draws out the wire, another straights it, a third cuts it, a fourth points it, a fifth grinds it at the top for receiving the head: to make the head requires two or three distinct operations: to put it on is a particular business, to whiten the pins is another … and the important business of making a pin is, in this manner, divided into about eighteen distinct operations, which in some manufactories are all performed by distinct hands, though in others the same man will sometime perform two or three of them.”

Why should we care about how many people it takes make the pins, or how many steps are in the process? Well, Smith found that by creating a process and assigning the steps to individual specialists, productivity increased 24,000%.

The workings of an 18th Century pin factory, and the image that inspired Adam Smith to write the first definition of a business process.

Using processes to work 5 times faster

A process is necessary for the division of labor because the task isn’t just in one person’s head anymore.

The full-stack pin engineer might be a fine person to write the process, but shouldn’t be running it from start to end alone — the job is 240 times more efficient when it’s split up amongst pin specialists: the person who cuts pin wires all day is less fallible than the solo pin master craftsman. Let’s stop talking about pins.

On a winter morning in 1907, Henry Ford took Charles E. Sorensen to Piquette Avenue Plant, an empty building in Detroit that would go on to become the birthplace of America’s first mass-produced affordable car. “We’re going to start a completely new job” he told the head of production.

The Piquette Avenue Plant in Detroit, Michigan. The site of the world’s most influential business process implementation.

Ford explained his idea for a new process. Instead of one artisan creating a product alone, everyone was taught to do one of 84 simple, repetitive jobs. With this new approach to processes, Ford cut the manufacturing time of the Model T down from 12.5 hours to 2.5 hours.

Not only was that a triumph for Ford’s bank account, it was one of the most revolutionary moments ever to occur, not just in the history of cars or manufacturing, but in the entire history of business.

The three types of processes every business needs

You know that processes are a set of logical instructions to be executed from start to end, but did you know that there are three types of processes? These are:

- Management processes

- Operational processes

- Supporting processes

Management Processes

Management processes aren’t as laser-focused on taking a task from start to finish as they are focused on planning and projecting the future of company operations.

An example of a management process might be a CEO planning out how best to organize the marketing team’s time and energy for a PR launch campaign. The process part would be allocating resources, defining timeframes and checking that the systems are in place and optimized.

Operational Processes

Operational processes concern your core business process. If you’re a t-shirt company, one of your core operational processes is taking orders over the phone. Another would be getting manufactured t-shirts off to be shipped.

Whatever your business does at its core, there should be watertight processes in place to make your business scalable and efficient.

Supporting Processes

Surprise surprise — supporting processes support the management and operational processes. The company relies on these processes to prop up the planning and doing parts of the business. Its processes like tech support, employee onboarding or hiring an intern.

While these aren’t what the company does to make money, they facilitate the main revenue stream and make it so the management processes have something to manage, and that the operational processes are as friction-free as possible.

The anatomy of a process

When a process is documented on paper (or hopefully, digitally), it’s done in the form of a standard operating procedure document. While they aren’t the kinds of things you’d take to read on an 18-hour flight, they do make processes much easier to understand, distribute, teach, and optimize.

An SOP can contain:

- A header with the title, date, author and ID

- A step-by-step list of instructions

- The team or individual responsible for executing each task

- The resources (equipment, money, time, supporting teams) that the user will need

- References to other SOPs

Typically, enterprises and government bodies will create complex SOP documentation. Click here for an example of an introduction document to a set of SOPs created by General Electric for employees working with UNICORN controlled systems. You’ll notice there’s a table of code number and SOP designations as well as explanations of terminology.

… But sometimes, an SOP won’t be this complicated.

Smaller companies write efficient processes that just get the job done, and there’s less need for author, and SOP ID, when they are written with SOP software that will create that manually. The same goes for the references section, which is now done with hyperlinks. Below is a simple SOP created by Process Street:

The problems processes solve

In The Checklist Manifesto — a book we can’t stop talking about — Atul Gawande talks about how he implemented a safety process at Johns Hopkins hospital.

It seemed simple, and it wasn’t as cool as the other ideas they’d had, like robotic surgery. But in reality, it was the most effective tool that could have been implemented, and it was just a sheet of paper.

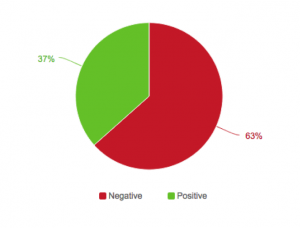

Surveyed after the checklist’s implementation, 78% of medical staff at the hospital said they noticed the checklist preventing an error. And, the ultimate proof: 93% of surgeons would want the checklist to be used on them if they were in the operating theatre undergoing surgery.

This is the process:

This next example is a more tangible, disastrous one.

On the morning of the hottest day of the year — July 17, 1865 — two trains packed mostly with children collided in Whitemarsh Township, Pennsylvania, killing around 60 and injuring over 100.

A painting of The Great Train Wreck of 1856 by an unknown artist

The cause? Wikipedia has it listed as ‘human error’.

The trains were pulling far more carriages than they could handle, meaning the drivers had to stop periodically to regain the engine pressure they needed to continue. With this erratic behavior, the train wasn’t on schedule and didn’t communicate that to the surrounding stations.

The driver thought he could make up for lost time and stay on schedule, so he gunned the engine, taking an alternative track and thinking that he’d be clear of the Aramingo, another train pulling out of Wissahickon around the same time.

On a blind bend, the boilers of the two trains impacted and caused an explosion heard up to 5 miles away. The three carriages closest to the boilers were blown to splinters, and the rest caught fire and derailed.

In response to this disaster, North Pennsylvania Railroad adjusted their processes. They ruled that no two trains traveling in two directions will share the same track, and telegram communication with nearby stations was made mandatory.

Using processes in your business

Nowadays, businesses don’t (usually) wait until catastrophic failure strikes before giving a thought to processes. If you’re not formally using processes, it’s never too early.

Business & Finance Articles on Business 2 CommunityThis article originally appeared on Process Street and has been republished with permission.

Find out how to syndicate your content with Business 2 Community.

(104)

Report Post