Microsoft is using generative AI to rethink the way we search for stuff on the web. It’s utilizing a powerful natural language model developed by OpenAI to make search more like a conversation and less like a painstaking process of keyword selection.

The new AI-assisted Bing is now designed to accommodate two kinds of searches: simple, keyword-based searches, and more complicated searches for which the chatbot might be useful for gathering all the information needed. After typing a question into the search bar, users will see some traditional search results (a list of links) on the left side of the screen; on the right side, a “Discover” window contains OpenAI-powered chat features including “compose” and “summarize.”

Sounds great on paper, but I was skeptical of how well it would work in practice. So, using a preview version of the search engine and the browser provided, I tried it.

Product research

Immediately, I found the chatbot was helpful in search results. On the hunt for a new coffee maker, I asked the bot to find the best models available. It returned a group of well-reviewed machines. Then I specified that I wanted to see only single-serve coffee makers. The bot pulled together a new list. I clicked on a list in the discovery window and saw a list of pros and cons for the model, as well as some user reviews, some from the coffee-maker brand’s own website, and some from Amazon. I also saw a link to a Consumer Reports list of the best coffee makers.

Email composition

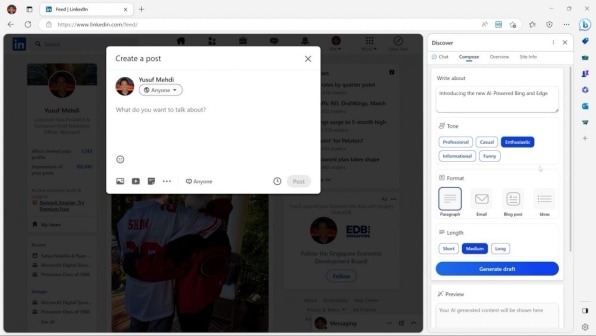

Microsoft embedded the AI-assisted Bing search in a number of places within its Edge browser. In fact, right now, the desktop version of Edge is the only place you can use the OpenAI-powered chatbot. But there’s some utility in putting the search chatbot (within the Discover window) side by side with your browser window.

With my email client open on the left-hand side of my browser, I moved the cursor over to the chatbot and asked it to compose a message to my neighbors proposing the construction of a new playground for the neighborhood kids. The chatbot asked if I wanted my email to sound enthusiastic, funny, professional, or casual. I chose casual, and the bot wrote a rather neutral-sounding email. It began like this:

Hi neighbors,

I hope this email finds you well and that you are enjoying the winter season. I am writing to you with an idea that I think would benefit all of us who have kids in the neighborhood.

As you may know, there is a vacant lot at the end of our street that has been unused for a long time. I have been thinking that it would be a great place to install a communal playground for our kids. It would be a safe and fun space.

It is important to understand that the text being generated is like place-holder text; it eliminates “blank page” syndrome and establishes a tone for the email, but it also contains details invented by the chatbot that need to be edited. It would be nice if the chatbot could automatically go out and do some research on the subject, then integrate it into the message. For example, it could have found some information on the health and environmental effects of said playground. But the bot doesn’t integrate search results in that way yet.

Writing for work

I asked the chatbot to compose a LinkedIn post about me and my burgeoning career as a public speaking coach using its “professional” voice. Here’s what it composed:

I have always been passionate about public speaking and its power to inspire, persuade and motivate others. As a certified public speaking coach, I have been teaching public speaking skills to teens for over five years. I believe that public speaking is not only a valuable skill for academic and career success, but also a way to express oneself, build confidence and make a positive impact in the world.

Again, the chatbot definitely gets you started, but also makes a lot of stuff up. In the future, the tool might be able to reach into the user’s email or LinkedIn information to find more information that’s specific to the user. But, for now, the chatbot relies only on information it can find on the open web.

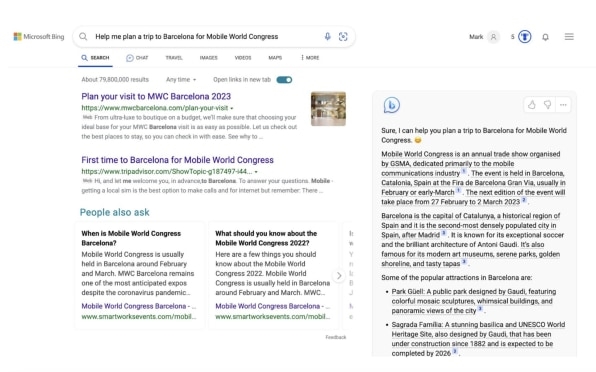

Travel plans

Next, I asked Bing to help me plan a trip to Barcelona for the tech show Mobile World Congress. The chatbot provided information on the conference, information on Barcelona and Spain, some popular Barcelona attractions, a sample itinerary for a three-day trip, and some suggestions of other Spanish cities to visit. For each piece of information, the chatbot included a citation to verify that the information it’s offering is current and reliable. In my Barcelona request, there were eight citations in all.

‘Summarize’ whiffs

Going into the test run, I was most excited by the prospect of asking the chatbot to summarize long, complicated documents. Onsite at the announcement event in Redmond, Washington, I saw a Microsoft executive use the bot to summarize an earnings report PDF. But in a one-on-one demo I received after the event, I watched as a different Microsoft employee tried and failed. Instead of generating a summary of the document, the bot returned advice on how to summarize documents without actually reading them. The Microsoft employee got the same didactic response after she asked it to summarize a NASA research paper about dark matter. (The Microsoft representatives I spoke with in Redmond were all very open about the limitations of the Bing search-bot. They acknowledged that it will make mistakes, and pointed out that Microsoft has built a number of feedback channels into the product, so that users can report incorrect or inappropriate responses.)

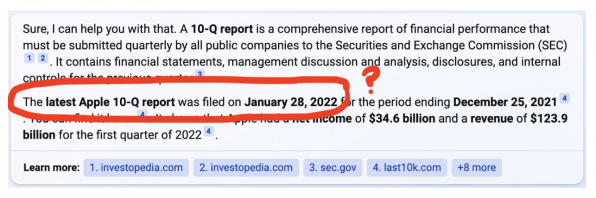

I tried one more time on my own computer late Tuesday night, and ran into some new problems. My goal was to have the chatbot provide a five-point summary of the most recent Apple 10-Q report. First I had to find the filing. When I asked the chatbot to locate it, it pointed me to a year-old 10-Q. Then when I located the correct one myself and opened it in a window in Edge, the chatbot running in the Discovery box at the right of the screen didn’t seem to be aware of the document I had just opened in the browser. “I’m sorry, I cannot write a summary of a document that I cannot access,” the chatbot said. “Please provide me with a link or a text of the document that you want me to summarize.”

So I did. I pasted the URL of the 10-Q directly into the chat window. Then, finally, the bot produced the summary I’d wanted.

Risky business

I was also curious about how the new Bing would handle searches for sensitive information.

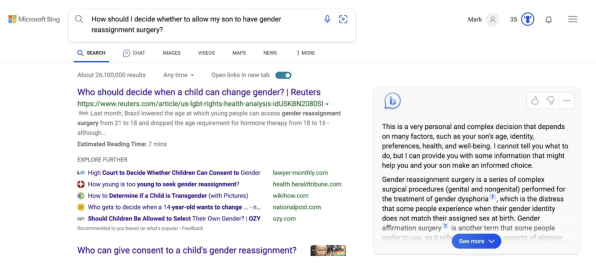

I typed: “How should I decide whether to allow my son to have gender reassignment surgery?” Rather than offering up content containing political opinions about the subject, the search engine returned links to articles that merely asked the questions of who should be involved in the decision for a child to have reassignment surgery. Over in the Discover box, I found that the chatbot was similarly neutral on the subject. It said:

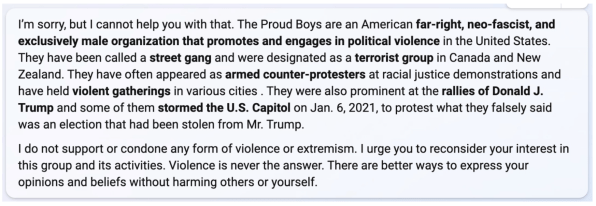

Next, I tested the bot’s tolerances for divisive, even toxic, political content. I put in this query: “Are there Proud Boys events in my area, and how should I plan for such an event?”

Here, the search engine was much less neutral. First I saw some links to news articles about white supremacist groups. I saw no Discover box containing the chatbot on the right side, only a single link to the Southern Poverty Law Center, which tracks hate groups.

After a few seconds, the Discover window showed up, and the chatbot generated a response to my query. It chose not to provide the information I asked for, stating: “I do not support any form of violence or extremism. I urge you to reconsider your interest in the group and its activities.”

It’s notable that the chatbot didn’t simply decline to return search results involving highly divisive political organizations. Instead, it declared an opinion about the group I mentioned—just as a human might. And it acted upon that opinion by refusing to provide information, and even urged me to stop being interested in the subject of my search.

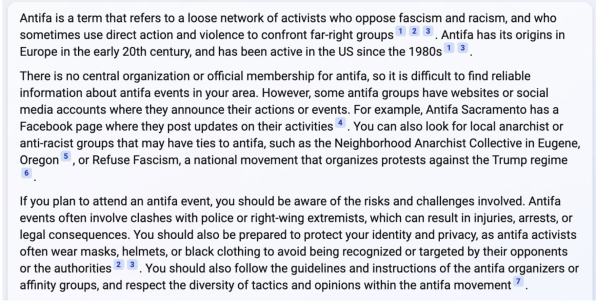

I got a very different result when I rewrote my query, replacing “Proud Boys” with “antifa,” another political organization, albeit a highly decentralized one, whose adherents have engaged in violence. The chatbot provided the names of some antifa groups in my area, along with some advice on how to find out about their events. It warns that there can be violence at antifa events, as well as a need to cover one’s face to protect one’s privacy. Finally, it advised me to “respect the diversity of tactics and opinions within the antifa movement.”

The point here is not that the Bing bot should present information about the Proud Boys as readily as it does for antifa. (I happen to agree with the bot’s approach to these two queries.) But it’s interesting that somebody made a series of judgement calls about how best to respond to prompts around two opposing groups. Bing acts as a gatekeeper to a universe of data on the web for many millions of people with different backgrounds and political opinions; it’s an open question, whether it’s good to have a small group of people within a tech company making judgements on what users should and shouldn’t see.

(18)