— July 31, 2017

I don’t think I am exaggerating too much when I say that the political scene in Washington is a rotten mess. Congress is completely paralyzed by its own self-inflicted anaphylactic shock. The pathogen? Leadership blindness. It seems that politicians, on both sides of the aisle, have become so fixated on specific outcomes that they no longer see how to lead the American people by establishing sound public policy.

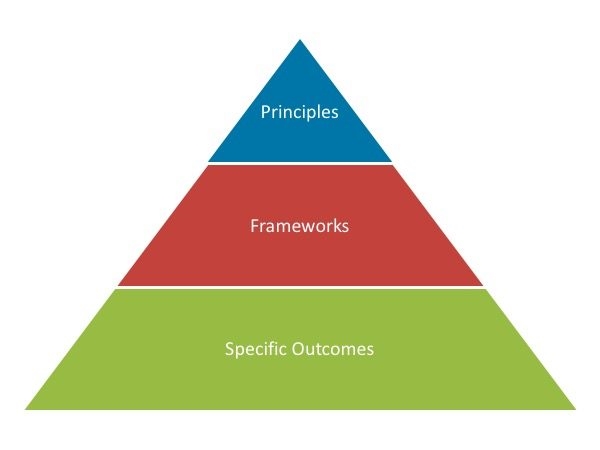

When leaders sit down to govern, whether in the private or public sectors, they are responsible for three policy tiers that govern the relationships (and accompanying expectations) that exist between management and their employees or constituency. In the business world, we call this overarching relationship, the Employee Experience. In the case of politicians, we might call it the citizen experience. A common way in which the Employee Experience or citizen experience breaks down is when leaders fail to understand what is required of them within each of these three tiers.

I have organized these three policy tiers into what I call the “Policy Pyramid.” At the top are the organization’s governing principles, with the organization’s First Principles forming the apex. An organization’s principles are those values and beliefs that inform where the organization wants to go and what it wants to be. “First Principles” are those principles that are unique to the organization and which are adopted solely for that organization.

Here are some examples of organizational principles. For Apple, they value innovation and beautiful design. In the case of Starbucks, they focus on quality and communal experiences. In the United States, we value freedom of speech and other key characteristics of liberty.

An organization’s governing principles range from a few to several, depending on each organization’s circumstances. And, these principles differ across the board depending on market needs, mission, etc. For example, some may advocate for gender diversity (Morgan Stanley) while others may push for unparalleled customer service (Nordstrom).

In the middle of the Policy Pyramid is what I call the expectation framework. In this tier, leaders work on establishing rules and procedures that promote positive behavior and limit negative conduct. It should be noted that a good framework is not necessarily focused on creating specific outcomes. Instead, a well-designed framework promotes efficient micro-markets or creates well-functioning communities.

As stated, it’s best if a framework is outcome agnostic. Here’s an illustration. Consider a tech start-up that is interested in closing the gender pay gap. Its CEO establishes a policy that hiring managers should not make a salary offer that is based on an applicant’s prior compensation levels. The policy prohibits managers from asking applicants what type of compensation they received from prior employers. This policy is agnostic. It does not create rigid pay bands, nor does it require that all women receive a set compensation amount. Instead, it is indifferent to the amount of compensation and lets the internal hiring “micro-market” take care of itself. Frameworks like these allow for variance and promote market forces without requiring rigidity or specific outcomes.

At the bottom of the Policy Pyramid are specific outcomes. These are tightly-worded policies that say things like, “If you work for us for two years, you will automatically be promoted.” Or, all children under the age of 12 must receive healthcare regardless of their ability to pay.” Outcome-based expectations are important, but they are difficult to manage, especially within large populations and by leaders who are removed from what is happening on the ground.

Here is a possible case study to consider. A hospital was worried about reducing the number of patients that were falling and injuring themselves. Management sent out an organization-wide memorandum mandating that, “All patients that are up and walking around must be accompanied by a staff member at all times.” The problem is that there was no buy-in from those best able to police the situation, and it was unrealistic to think that in every instance a staff member would be present when a patient decided to walk around. The policy felt like a mandate from an out-of-touch leadership team.

Leaders get into trouble when they focus on a section of the pyramid that does not correspond with their level of responsibility. The natural tendency is for most to go right to the bottom and start working on specific outcomes. Yet, note how the Policy Pyramid follows the same shape as an organizational pyramid. CEOs and executives are responsible for policies. Senior leaders are responsible for frameworks. Team leads and supervisors are responsible for specific outcomes.

Right now, in the healthcare arena, Congress is trying to draft legislation that produces specific outcomes; e.g., this many people will be given Medicaid or all pre-existing conditions will be covered. Instead, Congress should first be clear on its governing principles: who should be covered, where, when, how, and who pays. Once those principles have been established, then, in my view, Congress’s primary job is to work on a framework that promotes an efficient marketplace and incentivizes behaviors that are aligned with these principles. Adam Smith’s “invisible hand” will take care of the rest, and the market will find innovative solutions to drive specific outcomes.

Congress is too focused on the outcomes, and since no one will ever agree on the precise details, healthcare reform seems destined for failure. Health insurance companies don’t need politicians to tell them how to deliver healthcare. They need politicians to create regulatory frameworks that promote efficient and fair marketplaces.

The same is true in business management. Let’s go back to our example of the hospital that was trying to limit episodes where a patient falls. The CEO and other executives are responsible for the hospital’s governing principles, which should include an emphasis on patient safety and care. Senior management implements these policies by developing frameworks. For example, at this level, senior management might implement an employee recognition system that finds positive behavior and rewards it. Finally, at the team-level, supervisors are empowered to work on specific outcomes as they see fit. It’s also at this level where they have actual visibility into whether something is happening or not. Here, one-on-one meetings can address performance issues, including whether an employee has been ensuring that someone is present when a patient leaves his or her bed.

Again, leaders and politicians get into trouble when they focus on a level of the Policy Pyramid that does not correspond with their level of responsibility. The natural tendency is for most to go right to the bottom and work on the specifics. This tendency can be very problematic, as evidenced by the GOP’s current struggle with healthcare.

Business & Finance Articles on Business 2 Community

(74)

Report Post