None of us should be satisfied with what we believe brands to be capable of.

Whatever we believe that capability, it can be more.

When Henry Jenkins first introduced Transmedia in his treatise, Convergence Culture (2006), he spoke of ‘media formats’ as ‘entrypoints into a story world’.

Jenkins talked not of brands but of ‘media’ as a story-telling tool.

On April 6th, 2010, the Producers Guild of America announced the addition of ‘Transmedia Producer’ to the Producers Code of Credits. A big deal (that some termed ‘unprecedented’), it marked the first time in the guild’s 60-year history that a new credit had been added to the list.

At the time, no one was thinking of a Transmedia Producer as anything other than a person – and certainly no one was thinking about brands.

Five years on… and it is high-time we consider the greater potential for brands as ‘story-world entrypoints’ and transmedia producers.

Simply, we need to think differently – more ambitiously – about what can happen when you bring together the worlds of entertainment and marketing.

We need to shrug off near-ancient, limiting definitions like “product placement” and “commercial interruption”, because these definitions hinder new ways of approaching the creation and funding of entertainment.

We’ve come a long from Mike Myers in Wayne’s World, mugging ironically as he flips the lid on a delivery from Pizza Hut.

Rather than brands as jarring interlopers within a story, we must explore how they can facilitate the creation of entertainment, and even enhance the content being made.

When director James Cameron wanted to explore the Mariana Trench (and document the expedition as an independent movie), he turned to Rolex.

In Deepsea Challenge 3D (2014), Rolex effectively serves as co-producer in the film’s funding, with logo presence on the final theatrical poster, side by side with National Geographic and Disruptive LA.

Rolex subsequently released the Rolex Deepsea with D-Blue dial. Watch buffs could barely find words to express how radical an act this was for Rolex, suggesting the luxury brand paragon to be breaking and beginning a very different commercial and creative direction to its past.

When director Sam Mendes took to the Pinewood stage on December 4th last year, announcing the 24th Bond movie to be Spectre, he also lifted the veil on the new Aston Martin DB10. No one groaned. No one derided the moment as gratuitous product placement. Rather, flashbulbs popped and a delighted Andy Palmer, CEO of Aston Martin, emphasised:

“In the same year that we celebrate our 50-year relationship with 007, it seems doubly fitting that we unveil this wonderful new sports car created especially for James Bond.”

In reality, Aston Martin will use Spectre as the platform for what will not be a one-off sports car, but the design direction of their remodelled Vantage. In 2017, anticipate straplines to the effect, “Built for James Bond. And now for you.”

Land Rover/Jaguar are also keenly in on the act, Spectre becoming the latest instalment in their ongoing brand renaissance. The Range Rover Sport SVR and Defender Big Foot will grab precious screen time, while Jaguar’s web site proudly spoiler-alerts, “The C-X75 will feature in a spectacular car chase sequence through Rome alongside the Aston Martin DB10”.

To label Aston Martin and Jaguar as mere product placements in Spectre is to miss the bigger picture. These are partnerships: brand integrations that add further layers upon the narrative world.

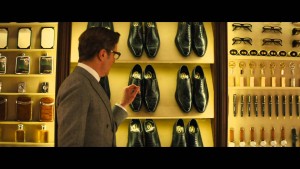

This year’s Kingsman, from 20th Century Fox, is a positive roll call of Cool Britannia brands. Think: Turnbull & Asser, Deakin & Francis, Drake, George Cleverley, Cutler & Gross, Smythson, and Bremont.

Under the banner of ‘Curated British Luxury’, men’s style destination MR PORTER invites us to dress like a Kingsman, offering a 60 piece collection.

Across their own digital and social graphs, 8 eight brands (9 when you include Mr Porter) all excitedly promote Kingman (and their “hand-picked collaboration” with the movie), so driving trailer views and product purchase.

Once upon a time, this might have been called merchandising – but it surely becomes something far more sophisticated when it loops in director Matthew Vaughn and costume designer Arianne Phillips at the pre-production stage.

Kingsman effectively presents retail brands as Transmedia entrypoints, fuelling movie anticipation, but more interestingly offering us the physical and mental props to get us in-character and wish-fulfilling.

It is clear that the entertainment business is learning the language of brands (and marketing) – and it will arguably do so faster than the agency world can learn how to make legitimate and singularly entertaining content.

Directors like James Cameron, Sam Mendes and Matthew Vaughn are showing us what the intersection of entertainment and marketing can look like: where brands can become buzz builders and movie co-producers, where they can become wish-fulfilment props and Transmedia portals.

I’m reminded of a scene from Robert Altman’s The Player (1992).

Griffin Mill: It lacked certain elements that we need to market a film successfully.

June: What elements?

Griffin Mill: Suspense, laughter, violence. Hope, heart, nudity, sex. Happy endings. Mainly happy endings.

June: What about reality?

Reality notwithstanding, to Griffin’s list I wonder, can we add ‘brands’?

(216)

Report Post