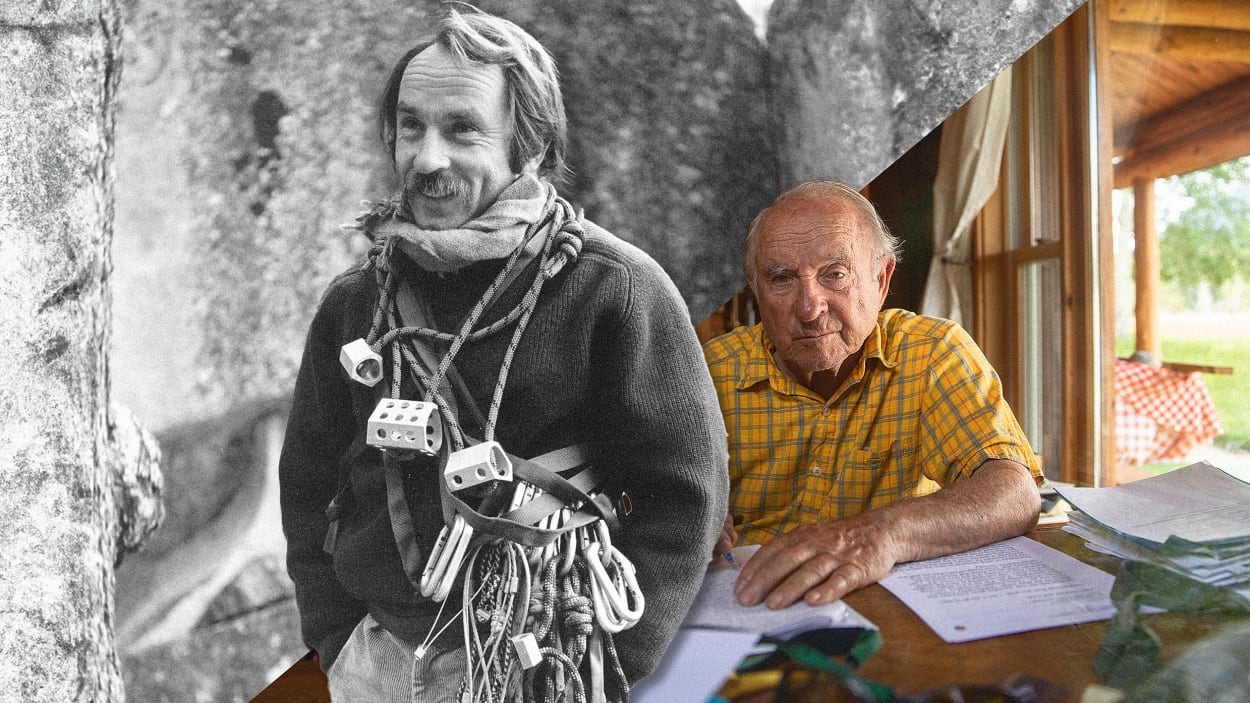

Author Jim Collins (Good to Great, Built to Last) has been chronicling Patagonia’s unique approach to business since the late 1980s, when he wrote and taught a case study on the company for his Stanford Graduate School of Business classes on entrepreneurship. He has written for Inc. about how Patagonia has used its brand to effect social change, and in a Fast Company interview published in 2021, he highlighted company founder Yvon Chouinard as an example of leadership “done right.” Collins also is an avid rock climber who has an original copy of Chouinard’s 1972 manifesto for clean climbing. So when the Chouinard family said it was transferring its voting stock to a special trust and the rest of the shares to a nonprofit, we immediately wondered: What does Jim Collins make of this? He spoke exclusively to Inc. and Fast Company chief content officer Stephanie Mehta about Chouinard’s legacy, and how the iconoclastic entrepreneur has redefined the term “exit strategy.” Edited excerpts follow.

Stephanie Mehta: What was your initial reaction when you heard the news that the Chouinard family was going to give up ownership of Patagonia through this unique structure designed to preserve its independence and its commitment to climate change and conservation?

Jim Collins: The idea that they are going to try to put in place a structure that will allow the values, purpose, and integrity to continue beyond the founder is emblematic of the Built to Last philosophy on a large scale. My reaction was one of admiration. Yvon is someone I find almost intimidating in his purity.

[Photo: Denver Post/Getty Images]

SM: He’s certainly been very consistent.

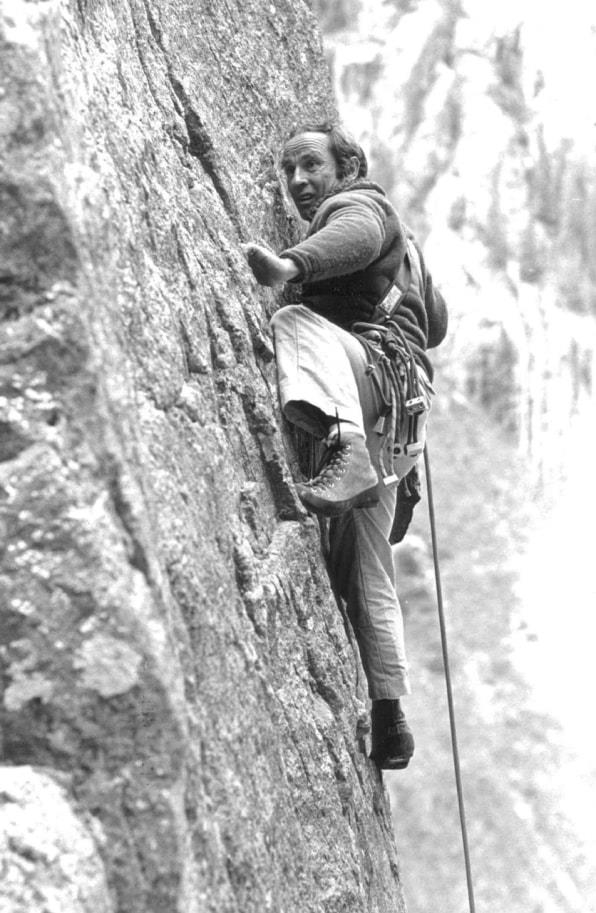

JC: Clarity of understanding of what you’re about has translated into a series of consistent decisions over a very long period of time. My wife, Joanne, immediately pointed out that Chouinard did not sell control to fuel growth, and that gave him freedom. And he didn’t pursue growth per se. Growth was a result of incredible products, incredible execution, and superb branding, which translated into margins and cash flow that could continue to fuel expansion at a consistent pace over time. This isn’t a five-year story. This is a five-decade story. It starts with selling pitons (pegs that support climbers) out of the back of a car and then the soft goods and more. Compounding consistently over time, while retaining control, gives you the freedom to make decisions that align with what your company’s about.

SM: How innovative is this move? There seem to be very few precedents.

JC: Let’s call it a big and wonderful experiment. When the Constitution was written, it was an experiment. We didn’t know a hundred percent if it would work because there hadn’t been one before.

We tend to think of product and technology types of innovations. The really cool use of new fabrics or the next wave of biotechnology drugs. But when you look over the long course of corporate history, the even more profound than product innovation is organizational innovation.

If the Chouinard family’s restructuring works, if it’s successful, it could be a new evolution for some companies and how they evolve over time. It would be far more impactful than the R-1 jacket. By the way, I’m wearing an R-1 right now, which I love.

[Photo: Plate from Royal Robbins: Spirit of the Age by Pat Ament/Wiki Commons]

SM: Another thing we can’t know, but can potentially speculate about, is what the structure will mean for Patagonia as a company. On the one hand, you could say this is only going to further attract talent who care deeply about the mission. But if the common shares are owned by a nonprofit, will people be less incentivized to maximize sales and profits?

JC: When I taught this at Stanford, it was very clear that maximizing sales and profits was not the primary goal. Then-CEO Kristine McDivitt would say: “That’s not how we look at things. We’re not a shark that just has to go as far as possible and eat as much as possible.” I could see my students wrestling with it because the company was incredibly successful. It had great products at superb margins, great branding, and cash flow that could be reinvested to fuel more of what the company was all about. Maximizing revenue and profit never has really been the way Patagonia framed things.

One of the concepts that has come out of our work is the flywheel effect. One side of the flywheel, the 12 o’clock to the 6 o’clock positions, is kind of the company is doing different things, making great products, driving down Moore’s law, delivering great health outcomes for the Cleveland Clinic, or great investment returns for Vanguard. On the other side of the flywheel, you convert all that into fuel and that translates into profit or resources and reputation. A really great flywheel is all about taking all that fuel that gets generated back into the top of the flywheel, so that you can then drive down the other side and do more actualizing of your purpose in the world.

I think Patagonia has a great flywheel. It was about focus on great products, a focus on how it actualizes its purpose in the world, and as it comes up the other side, doing it in a way that converts to fuel that can be used to fund the things it cares about in the outside world and do more in terms of what it is all about as a company.

I don’t think it really matters who owns the company for that flywheel to work. No, I take that back. If someone who owned it wanted only to extract those profits, that could slow the flywheel. Given the history of the company, the basic flywheel has been purpose, fuel, purpose, fuel, purpose, over and over again.

SM: But even in a purpose-driven organization, the flywheel needs to work. Because the better the institution does, the greater the resources for the cause.

JC: Right. The flywheel needs to keep spinning with the sheer exquisite excellence of the products and the materials and the innovation.

[Photo: Kyle Sparks/courtesy Patagonia]

SM: In 1997, Inc. published an article from you that highlighted the way Patagonia used its platform for social change. You wrote: “The modern business organization stands as one of the most powerful tools ever invented by man. Business leaders of all persuasions and temperaments can legitimately use their companies to stimulate social change.”

JC: Did I really write this? It’s almost a good sentence.

SM: Then, in 2019, Fast Company put Yvon on the cover, and there was an outpouring from young founders who thanked the editors for putting him on the cover. Might Yvon’s enduring legacy not be just using Patagonia to stimulate social change, but also inspiring a new generation of founders to experiment with ownership structure to ensure that the values endure?

JC: I hope that more founders, before they get drawn into the “What everybody else thinks their company or business should be,” start first with their own declaration of independence: This is our truth. This is what we hold self-evident. And do it. Do it early before we lose the ability to control our own destiny. Make your decisions in ways that allow you to not sell control or to fuel growth that you might not even want. And, then begin to build.

And when people ask: What’s your exit strategy? Boy, Chouinard just redefined that. This is like an existential exit strategy: He’s saying: This is what my life is about.

(13)