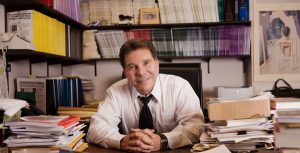

NEW YORK (AP) — After 46 years, Steve Replin has decided to give up his office space.

Replin, who has a law practice and acts as an alternative lender in Denver, is adapting to the changing preferences of clients, who would rather conduct business online, or in a less professional setting like a coffee shop.

“I am 76 and have grown up being in actual physical spaces as offices, but I really think that the ‘kids’ have it right,” by shunning offices, he said.

The pandemic has had a transformative effect on the office space landscape. Many businesses are shifting away from traditional spaces toward hybrid work and more flexible, collaborative spaces. About 23% of U.S. office space is available, compared with 16% before the pandemic, according to global real estate adviser Avison Young.

While the real estate decisions of big companies get much of the attention, small-business owners are also reassessing what they need in terms of an office. Some are finding more bang for their buck in suburban locations. Others are scaling back on square footage, and still others, like Replin, are contemplating a move to going permanently remote. Experts say the time is ripe to reassess what a small business actually needs.

“(Lower demand for commercial real estate) opens up an opportunity where I may be able to consider some change in my space because it’s either newer, it’s in a little bit better location,” said Alan Pontius, national director of the office and industrial division at commercial real estate brokerage firm Marcus & Millichap. “And maybe I can get that at the same or even a better rate than I have been paying just because of what’s happened with the movement of rental rates. So it it does open up some opportunity to consider new options.”

That’s true for Hunter Garnett. When he started his law firm during the pandemic in December 2021, he signed a lease for 2,000 square feet of office space in downtown Huntsville, Alabama, because he thought it was important to set up shop close to the courthouse.

Garnett quickly realized that court appearances via Zoom were here to stay. He goes to court once every other week now, compared to two or three times a week before the pandemic when he worked at another law firm.

“I thought I’d be in the courthouse a lot and that I would grow fast and need more space,” he said. “And then I did grow fast, but I figured out pretty quickly that it was more economical to hire remote workers, so our need for physical space didn’t grow as fast as I expected.”

Garnett is looking for a smaller space—1,200 square feet or so—in suburban Huntsville, closer to where most of his clients live. He expects to pay $1.50 a foot for rent, including parking, $1 less than what he pays now.

Leslie Saul also cherished her 31-year-old architecture and interior design firm’s central location in Cambridge, Massachusetts, which she’d had since 2000. But when her landlord doubled her $3,000 a month rent, she considered other options, including a suburban town. The pandemic taught her she could work in a smaller space, but she still saw value in having office space with a physical library.

“We wanted to have an identity,” she said. “We wanted to be visible.”

So, on January 1, she opened her new office in Winchester Center, a smaller town outside of Cambridge. The rent is cheaper because the new space is smaller and it includes parking. Saul said she was able to downsize her library, filled with samples and a necessary part of the firm’s office space.

“I think that this time around, I was definitely open to many options that I might never have been even considering before the pandemic,” she said.

For businesses that no longer have workers coming into the office full-time and have hired some remote staffers—two trends spurred by the pandemic —a coworking space can fit the bill.

Annie Scranton, who owns Pace Public Relations in Manhattan, is considering a coworking space that holds eight people. None of her staff of 20 comes into the current office full-time anymore—some live and work outside New York—but she wants a space that could entice a few workers to come in, at least on some days.

“Mostly staff is coming in when there are in-person client meetings, when there are events that they’re attending, you know, that then it’s easy to work from the office or when there are in-person planned, like brainstorming creativity sessions,” she said.

Some business owners are even deciding to give up office space altogether. Replin said he’s meeting clients in coffee shops or by video chat. He finds organizing these meetings is quicker and easier than in-office visits.

“I can get a meeting put together in an afternoon, whereas sometimes it took a week or two to find a day when they could allocate a 45-minute drive to my office, an hour appointment, and then a 45-minute drive back to wherever they came from,” he said. “So, it’s just it’s amazing. It’s night and day.”

Replin plans to let his lease expire when it comes up in three months. And it’s not just him: He’s noticed vacancies on every floor in his 11-story office building.

Muffetta Krueger’s cleaning and household staffing businesses boomed during the pandemic, and she realized she could grow in some areas without adding more office space. She has two physical offices in Larchmont, New York, and Greenwood Lake, New Jersey.

She planned to look for office space to expand in Maryland, near the D.C. metropolitan area, but decided she could manage operations there remotely—at least at first. Now, they send candidates applications online and conduct video interviews rather than having them come into an office.

“If we’re able to operate and keep our costs low, there is no reason to burden ourselves with real estate,” Krueger said.

—Mae Anderson, Associated Press

(20)

Report Post